|

|

- Search

| Korean J Fam Med > Volume 43(2); 2022 > Article |

|

Abstract

Spinal epidural abscess (SEA) caused by Escherichia coli is an uncommon condition. It usually occurs secondary to urinary tract infection (UTI), following hematogenous propagation. Disruption of spinal anatomic barriers increases susceptibility to SEA. Although rarely, such disruption can take the form of lumbar spine stress fractures, which can result from even innocuous activity. Here, we describe a case of SEA secondary to UTI in a patient with pre-existing stress fractures of the lumbar spine, following use of an automated massage chair. Successful treatment of SEA consisted of surgical debridement and a six-month course of antibiotic therapy.

Infectious spondylodiscitis with spinal epidural abscess (SEA) is a rare but severe infection requiring immediate diagnosis. Risk factors for SEA include diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, intravenous drug abuse, and degenerative joint disease [1]. Escherichia coli is an uncommon cause of SEA, but can be the causative microorganism secondary to urinary tract infection (UTI) [2]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of SEA in a Korean patient with pre-existing stress fractures. Specifically, we describe a case of SEA secondary to UTI in a patient with pre-existing stress fractures of the lumbar spine.

An 85-year-old Korean male presented with fever (38.4°C), flank pain, and a history of benign prostatic hyperplasia, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, and left nephrectomy due to renal cell carcinoma 10 years prior. Blood analysis demonstrated a total leukocyte count of 14.0×103 cells/mL, a serum creatinine level of 2.0 mg/dL (determined as elevated relative to a reading of 1.8 mg/dL 6 months previously), a C-reactive protein level of 24.4 mg/dL, and a hemoglobin A1c of 9.1%. Urine microscopy demonstrated 20–29 leukocytes/high power field, non-contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) demonstrated perirenal fat infiltration of the right renal pelvis, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to exclude infectious spondylitis incidentally demonstrated stress fractures of lumbar vertebrae L3 and L4 (without evidence of SEA). The patient’s history was negative for trauma or strenuous exercise, however, the patient did undergo several days of 15-minute automated massage. Intravenous cefotaxime was administered for a presumed diagnosis of UTI concomitant with lumbar spine stress fractures; urine and blood cultures subsequently yielded cefotaxime-sensitive E. coli, thus confirming the diagnosis.

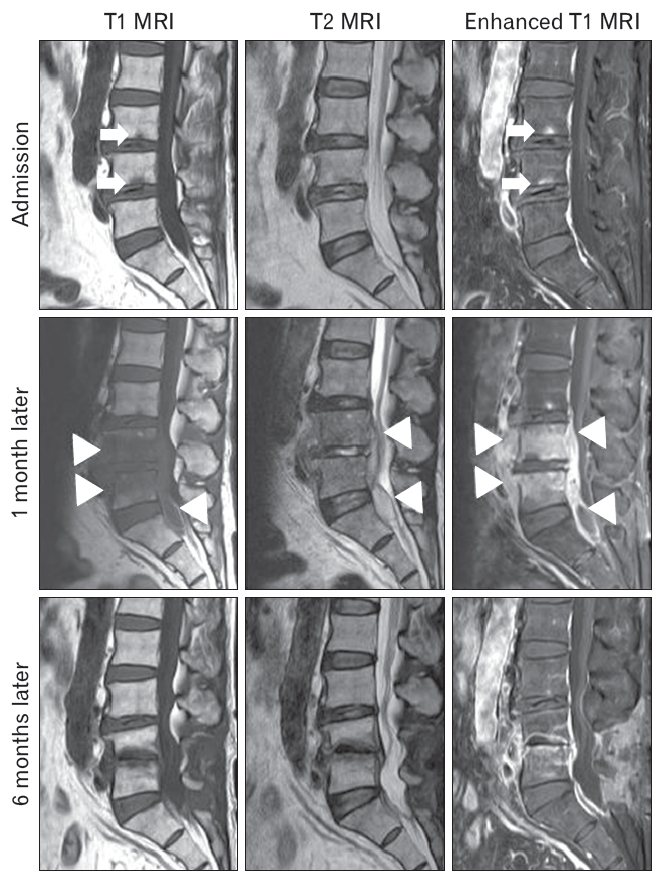

Although an initial 2-week antibiotic treatment decreased inflammatory marker levels, cessation of cefotaxime treatment precipitated fever and increased inflammatory marker levels. Furthermore, the patient complained of lower back pain. Therefore, we performed non-contrast-enhanced CT to assess the genitourinary system and detected infectious spondylitis with SEA as a result. Repeat lumbar MRI indicated SEA anterior to the lumbar and sacral vertebrae (L3–S1) (Figure 1). The patient underwent urgent decompressive left laminectomy of L4–S1 with epidural abscess drainage and irrigation. Disc tissue protruding into the spinal canal was also removed. The abscess culture was positive for E. coli. Continuation of antimicrobial treatment for a further 6 months prevented SEA recurrence, as demonstrated by follow-up MRI.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Bacteria can enter the epidural space via three potential routes: direct spread from adjacent tissues, hematogenous spread, and iatrogenic inoculation (e.g., lumbar puncture). In the case of hematogenous spread from a remote source, it is often skin, soft-tissue, or urinary/respiratory tract infections that are the primary source [1]. In general, the microorganism most commonly responsible for SEA are Gram-positive bacteria and staphylococci [2,3]; however, in approximately 3% of bacterial SEA, the infection is due to E. coli, usually in association with a concomitant UTI [2,4]. Although no large studies have investigated the incidence of SEA secondary to UTI in South Korea, Ju et al. [5] demonstrated that E. coli was the causative pathogen in three of 48 SEA patients. To prevent significant sequelae resulting from untreated SEA, a high level of clinical scrutiny is required in patients exhibiting new-onset infection during treatment for UTI.

Through disruption of anatomic barriers, spinal trauma is associated with hematogenous dissemination of microorganisms and subsequent development of SEA [6]. Stress fractures are common injuries resulting from placing excessive repetitive stress on bone [7]; however, vertebral compression fractures can occur in the elderly after even innocuous activity, such as using an automated massage chair [8]. Indeed, the patient reported herein exhibited massage-induced stress fractures of L3 and L4, which pre-dated UTI symptoms and was first noted as an incidental finding on MRI. The results of blood, urine, and abscess cultures were consistent with E. coli being the causative microorganism, strongly suggesting SEA secondary to UTI. Furthermore, the patient exhibited multiple SEA-predisposing risk factors including diabetes, chronic kidney disease, benign prostatic hyperplasia, and spinal abnormalities. Therefore, we recommend that UTI patients with vertebral fracture be closely monitored for signs or symptoms suggestive of SEA.

Since the mid-2000s, the use of automated massage chairs in South Korea has been increasing because of its cost-effective benefits for pain control [9]. However, careful attention is needed to avoid compression fracture while using a massage chair, especially in older adults. Additionally, clinicians should closely monitor UTI patients with spinal abnormalities, including vertebral fractures, for the development of SEA.

In summary, we report a case of SEA secondary to UTI in a patient with pre-existing stress fractures of the lumbar spine following use of an automated massage chair. The SEA was successfully treated via surgical drainage and antibiotic therapy.

Figure. 1.

Lumbar magnetic resonance T1-weighted sagittal, T2-weighted sagittal, contrast enhanced sagittal images. Admission lumbar magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showing stress fracture on L3 and L4 (white arrow). One month later, repeated MRI showing infectious spondylitis on L4, L5, and epidural abscess (white arrow head). Six months later, follow-up MRI showing decreased infectious sponsylitis and resolved epidural abscess.

REFERENCES

1. Sendi P, Bregenzer T, Zimmerli W. Spinal epidural abscess in clinical practice. QJM 2008;101:1-12.

2. Reihsaus E, Waldbaur H, Seeling W. Spinal epidural abscess: a meta-analysis of 915 patients. Neurosurg Rev 2000;23:175-205.

3. Curry WT Jr, Hoh BL, Amin-Hanjani S, Eskandar EN. Spinal epidural abscess: clinical presentation, management, and outcome. Surg Neurol 2005;63:364-71.

4. O’Neill SC, Baker JF, Ellanti P, Synnott K. Cervical epidural abscess following an Escherichia coli urinary tract infection. BMJ Case Rep 2014;2014:bcr2013202078.

5. Ju MW, Choi SW, Kwon HJ, Kim SH, Koh HS, Youm JY, et al. Treatment of spinal epidural abscess and predisposing factors of motor weakness: experience with 48 patients. Korean J Spine 2015;12:124-9.

7. Patel DS, Roth M, Kapil N. Stress fractures: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Am Fam Physician 2011;83:39-46.

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

-

- 1 Crossref

- Scopus

- 2,958 View

- 61 Download