|

|

- Search

| Korean J Fam Med > Volume 44(3); 2023 > Article |

|

Abstract

Background

Methods

Results

Conclusion

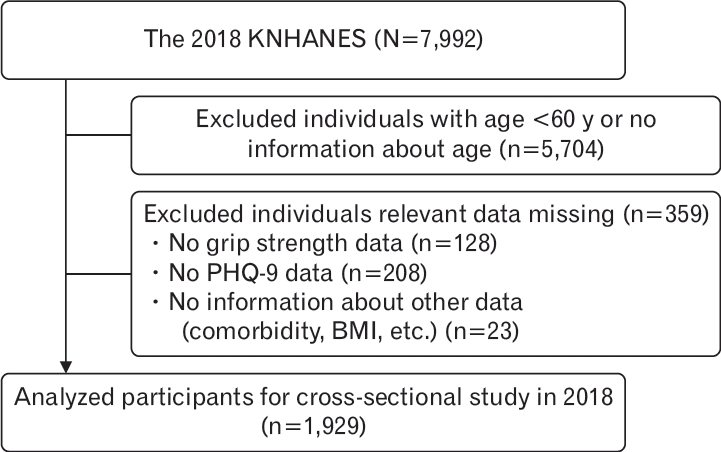

Figure.┬Ā1.

Table┬Ā1.

| Characteristic | Total (n=1,929) | Possible sarcopenia (n=538) | No sarcopenia (n=1,391) | P-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y)ŌĆĀ | 69.7┬▒6.5 | 74.1┬▒5.9 | 67.9┬▒5.9 | <0.001 | |

| Male | 861 (44.6) | 196 (36.4) | 665 (47.8) | <0.001 | |

| Ever married (vs. others) | 1,911 (99.1) | 533 (99.1) | 1,378 (99.1) | 0.991 | |

| Currently smoker (vs. others) | 198 (10.3) | 40 (7.4) | 158 (11.4) | 0.011 | |

| Drinking problemŌĆĪ | 390 (24.9) | 75 (19.0) | 315 (26.9) | 0.002 | |

| Chewing problem | 1,072 (55.6) | 337 (62.6) | 735 (38.1) | <0.001 | |

| Physical activity (per week)┬¦ | <0.001 | ||||

| Walking exercises | 1,163 (60.5) | 265 (49.5) | 898 (64.7) | ||

| Strength exercises | 318 (16.5) | 50 (9.3) | 268 (19.3) | ||

| Education level | <0.001 | ||||

| Elementary school or below | 806 (41.8) | 339 (63.0) | 467 (33.6) | ||

| Middle or high school | 847 (43.9) | 159 (29.6) | 688 (49.5) | ||

| College or above | 276 (14.3) | 40 (7.4) | 236 (17.0) | ||

| Household income (quintile) | <0.001 | ||||

| Upper (the 1st) | 589 (30.5) | 254 (47.2) | 335 (24.1) | ||

| Middle (the 2ndŌĆō4th) | 1,106 (57.3) | 244 (45.4) | 862 (62.0) | ||

| Lower (the 5th) | 234 (12.1) | 40 (7.4) | 194 (13.9) | ||

| Body mass index category | <0.001 | ||||

| Underweight | 35 (1.8) | 22 (4.2) | 13 (0.9) | ||

| Normal | 1,139 (59.9) | 323 (62.1) | 816 (59.0) | ||

| Overweight or obese | 728 (38.3) | 175 (33.7) | 553 (40.0) | ||

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Hypertension | 946 (49.0) | 303 (56.3) | 643 (46.2) | <0.001 | |

| Diabetes | 375(19.4) | 122(22.7) | 253 (18.2) | 0.025 | |

| Dyslipidemia | 576 (29.9) | 152 (28.3) | 424 (30.5) | 0.338 | |

| Stroke | 89 (4.6) | 36 (6.7) | 53 (3.8) | 0.007 | |

| Myocardial infarction | 50 (2.6) | 18 (3.3) | 32 (2.3) | 0.195 | |

| Angina pectoris | 90 (4.7) | 22 (4.1) | 68 (4.9) | 0.456 | |

| Arthritis | 502 (26.0) | 172 (32.0) | 330 (23.7) | <0.001 | |

| Osteoarthritis | 464 (24.1) | 154 (28.6) | 310 (22.3) | 0.003 | |

| Rheumatism | 53 (2.7) | 23 (4.3) | 30 (2.2) | 0.011 | |

| Osteoporosis | 285 (14.8) | 132 (24.5) | 153 (11.0) | <0.001 | |

| Asthma | 54 (2.8) | 18 (3.4) | 36 (2.6) | 0.366 | |

| Thyroid disease | 44 (2.3) | 8 (1.5) | 36 (2.6) | 0.146 | |

| Cancer | 63 (3.3) | 21(3.9) | 42(3.0) | >0.01 | |

| Anemia | 198 (10.7) | 103 (20.3) | 95 (7.1) | <0.001 | |

| Depressive disorder | 72 (3.7) | 35 (6.5) | 37 (2.7) | <0.001 | |

| Renal failure | 7 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 6 (0.4) | 0.422 | |

| Hepatitis B | 17 (0.9) | 4 (0.7) | 13 (0.9) | 0.687 | |

| Hepatitis C | 3 (0.2) | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.0) | 0.134 | |

| Liver cirrhosis | 12 (0.6) | 5 (0.9) | 7 (0.05) | 0.286 | |

| Depressive symptomsŌłź | 97 (5.0) | 42 (7.8) | 55 (4.0) | <0.001 | |

Values are presented as mean┬▒standard error for continuous variables and number (%) for categorical variables.

KNHANES, Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

ŌĆĪ Drinking problems were divided into two categories: yes, be recommended stop drinking alcohol or concerned about drinking by a doctor or family; no, never recommended or concerned.

Table┬Ā2.

| Age (y) | No. (%) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1,929 (100.0) | 2.06 (1.36ŌĆō3.11) | <0.001 |

| 60Ōēż Age <70 | 990 (51.3) | 2.41 (1.16ŌĆō5.02) | 0.019 |

| Age Ōēź70 | 939 (48.7) | 1.91 (1.09ŌĆō3.37) | 0.025 |

Model was adjusted for sex, marital status, education, household income, smoking status, drinking status, chewing problem, body mass index, physical activity, and comorbidities (hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, stroke, myocardial infarction, angina, arthritis including osteoarthritis, rheumatism, osteoporosis, asthma, thyroid disease, cancer, anemia, depressive disorder, renal failure, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, liver cirrhosis).

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidential interval.

Table┬Ā3.

| Items* | Symptomatic no. (%) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) for possible sarcopenia | P-valueŌĆĀ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Little interest or pleasure in doing things | 265 (13.7) | 0.96 (0.72ŌĆō1.28) | 0.778 |

| Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless | 245 (12.7) | 1.22 (0.91ŌĆō1.63) | 0.178 |

| Trouble falling or staying asleep, or sleeping too much | 567 (29.4) | 1.06 (0.86ŌĆō1.32) | 0.588 |

| Feeling tired or having little energy | 574 (29.8) | 1.16 (0.93ŌĆō1.43) | 0.186 |

| Poor appetite or overeating | 230 (11.9) | 1.48 (1.10ŌĆō1.98) | 0.009 |

| Feeling bad about yourself or that you are a failure or have let yourself or your family down | 182 (9.4) | 1.13 (0.81ŌĆō1.58) | 0.462 |

| Trouble concentrating on things, such as reading the newspaper or watching television | 126 (6.5) | 1.48 (1.01ŌĆō2.16) | 0.044 |

| Moving or speaking so slowly that other people could have noticed? Or the oppositeŌĆöbeing so fidgety or restless that you have been moving around a lot more than usual | 86 (4.5) | 2.13 (1.37ŌĆō3.29) | <0.001 |

| Thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way | 121 (6.3) | 2.74 (1.89ŌĆō3.97) | <0.001 |

* Measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Model was adjusted for age, sex, marital status, education, household income, smoking status, drinking status, chewing problem, body mass index, physical activity, and comorbidities (hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, stroke, myocardial infarction, angina, arthritis including osteoarthritis, rheumatism, osteoporosis, asthma, thyroid disease, cancer, anemia, depressive disorder, renal failure, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, liver cirrhosis).

REFERENCES

- TOOLS