|

|

- Search

| Korean J Fam Med > Epub ahead of print |

|

Abstract

Background

Methods

Results

Figure. 1.

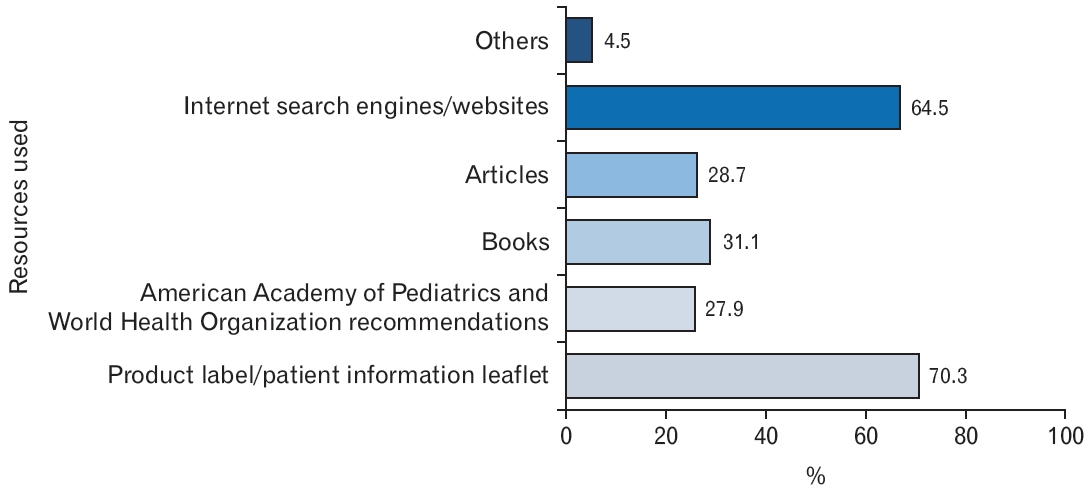

Figure. 2.

Table 1.

Table 2.

Table 3.

Table 4.

| Characteristic |

Confident level* |

Total | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unconfident | Neutral | Confident | |||

| Gender | 0.185 | ||||

| Male | 4 (7.7) | 8 (15.4) | 40 (76.9) | 52 (100.0) | |

| Female | 15 (4.6) | 29 (8.8) | 285 (86.6) | 329 (100.0) | |

| Age groups (y) | 0.719 | ||||

| 23–30 | 17 (5.7) | 32 (10.7) | 251 (83.7) | 300 (100.0) | |

| 31–40 | 1 (1.8) | 4 (7.3) | 50 (90.9) | 55 (100.0) | |

| 41–50 | 1 (4.5) | 1 (4.5) | 20 (90.9) | 22 (100.0) | |

| >50 | 0 | 0 | 4 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | |

| Marital status | 0.026 | ||||

| Single | 16 (7.2) | 28 (12.7) | 177 (80.1) | 221 (100.0) | |

| Married | 2 (1.3) | 9 (5.9) | 141 (92.8) | 152 (100.0) | |

| Divorced | 1 (14.3) | 0 | 6 (85.7) | 7 (100.0) | |

| Widow | 0 | 0 | 1 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) | |

| Do you have any children? | 0.060 | ||||

| No | 17 (6.4) | 29 (10.9) | 219 (82.6) | 265 (100.0) | |

| Yes | 2 (1.7) | 8 (6.9) | 106 (91.4) | 116 (100.0) | |

| Education levels | 0.237 | ||||

| BSc | 10 (4.3) | 23 (9.8) | 201 (85.9) | 234 (100.0) | |

| PharmD | 4 (4.2) | 7 (7.3) | 85 (88.5) | 96 (100.0) | |

| MSc | 5 (12.8) | 5 (12.8) | 29 (74.4) | 39 (100.0) | |

| PhD | 0 | 2 (16.7) | 10 (83.3) | 12 (100.0) | |

| Work location | 0.802 | ||||

| Urban (city) | 14 (4.7) | 30 (10.2) | 251 (85.1) | 295 (100.0) | |

| Rural (village) | 5 (5.8) | 7 (8.1) | 74 (86.0) | 86 (100.0) | |

| Personal breastfeeding experience† | 0.066 | ||||

| No | 12 (7.0) | 21 (12.3) | 138 (80.7) | 171 (100.0) | |

| Yes | 7 (3.3) | 16 (7.6) | 187 (89.0) | 210 (100.0) | |

| How frequently would you currently experience queries on medication use in breastfeeding (including multivitamins/nutritional supplements)? | 0.794 | ||||

| Seldom | 4 (7.3) | 7 (12.7) | 44 (80.0) | 55 (100.0) | |

| 1–2 per month | 4 (5.7) | 8 (11.4) | 58 (82.9) | 70 (100.0) | |

| 1–2 per week | 6 (4.7) | 13 (10.2) | 109 (85.2) | 128 (100.0) | |

| Daily | 5 (3.9) | 9 (7.0) | 114 (89.1) | 128 (100.0) | |

| Years of practice (y) | 0.123 | ||||

| <5 | 17 (5.9) | 31 (10.8) | 238 (83.2) | 286 (100.0) | |

| ≥5 | 2 (2.1) | 6 (6.3) | 87 (91.6) | 95 (100.0) | |

| Pharmacy type | 0.445 | ||||

| Independent pharmacy | 15 (5.4) | 30 (10.7) | 235 (83.9) | 280 (100.0) | |

| Chain pharmacy | 4 (4.0) | 7 (6.9) | 90 (89.1) | 101 (100.0) | |

| How frequently would you currently experience queries on medication use in breastfeeding (including multivitamins/nutritional supplements)? | 0.794 | ||||

| Seldom | 4 (7.3) | 7 (12.7) | 44 (80.0) | 55 (100.0) | |

| 1–2 per month | 4 (5.7) | 8 (11.4) | 58 (82.9) | 70 (100.0) | |

| 1–2 per week | 6 (4.7) | 13 (10.2) | 109 (85.2) | 128 (100.0) | |

| Daily | 5 (3.9) | 9 (7.0) | 114 (89.1) | 128 (100.0) | |

| How often do you ask women if the dispensed medications are for breastfeeding ladies? | 0.000 | ||||

| Never | 1 (33.3) | 0 | 2 (66.7) | 3 (100.0) | |

| Rarely | 4 (25.0) | 4 (25.0) | 8 (50.0) | 16 (100.0) | |

| Sometimes | 5 (5.7) | 10 (11.5) | 72 (82.8) | 87 (100.0) | |

| Very often | 2 (1.9) | 8 (7.7) | 94 (90.4) | 104 (100.0) | |

| Always | 7 (4.1) | 15 (8.8) | 149 (87.1) | 171 (100.0) | |

| How often do you consult a hard copy resource for breastfeeding women? | 0.005 | ||||

| Never | 5 (15.6) | 4 (12.5) | 23 (71.9) | 32 (100.0) | |

| Rarely | 9 (10.0) | 9 (10.0) | 72 (80.0) | 90 (100.0) | |

| Sometimes | 4 (2.8) | 16 (11.0) | 125 (86.2) | 145 (100.0) | |

| Very often | 0 | 4 (5.1) | 75 (94.9) | 79 (100.0) | |

| Always | 1 (2.9) | 4 (11.4) | 30 (85.7) | 35 (100.0) | |

| How often do you consult an online resource for breastfeeding women? | 0.484 | ||||

| Never | 2 (9.5) | 4 (19.0) | 15 (71.4) | 21 (100.0) | |

| Rarely | 2 (3.5) | 5 (8.8) | 50 (87.7) | 57 (100.0) | |

| Sometimes | 4 (3.2) | 13 (10.3) | 109 (86.5) | 126 (100.0) | |

| Very often | 9 (7.8) | 11 (9.5) | 96 (82.8) | 116 (100.0) | |

| Always | 2 (3.3) | 4 (6.6) | 55 (90.2) | 61 (100.0) | |

| How often do you receive prescriptions for medications that are not recommended in breastfeeding? | 0.335 | ||||

| Never | 1 (5.9) | 0 | 16 (94.1) | 17 (100.0) | |

| Rarely | 7 (6.5) | 14 (13.1) | 86 (80.4) | 107 (100.0) | |

| Sometimes | 10 (5.6) | 17 (9.5) | 152 (84.9) | 179 (100.0) | |

| Very often | 1 (1.8) | 6 (10.7) | 49 (87.5) | 56 (100.0) | |

| Always | 0 | 0 | 22 (100.0) | 22 (100.0) | |

| Product label/patient information leaflet | 0.732 | ||||

| No | 6 (5.3) | 9 (7.9) | 99 (86.8) | 114 (100.0) | |

| Yes | 13 (4.9) | 28 (10.5) | 226 (84.6) | 267 (100.0) | |

| American Academy of Pediatrics and World Health Organization recommendations | 0.660 | ||||

| No | 14 (5.1) | 29 (10.5) | 232 (84.4) | 275 (100.0) | |

| Yes | 5 (4.7) | 8 (7.5) | 93 (87.7) | 106 (100.0) | |

| Books | 0.572 | ||||

| No | 14 (5.3) | 28 (10.6) | 221 (84.0) | 263 (100.0) | |

| Yes | 5 (4.2) | 9 (7.6) | 104 (88.1) | 118 (100.0) | |

| Articles | 0.107 | ||||

| No | 17 (6.3) | 29 (10.7) | 226 (83.1) | 272 (100.0) | |

| Yes | 2 (1.8) | 8 (7.3) | 99 (90.8) | 109 (100.0) | |

| Internet search engines/websites | 0.907 | ||||

| No | 7 (5.1) | 12 (98.8) | 117 (86.0) | 136 (100.0) | |

| Yes | 12 (4.9) | 25 (10.2) | 208 (84.9) | 245 (100.0) | |

| Other | 0.383 | ||||

| No | 18 (4.9) | 37 (10.2) | 309 (84.9) | 364 (100.0) | |

| Yes | 1 (5.9) | 0 | 16 (94.1) | 17 (100.0) | |

Values are presented as number (the distribution relative to each row %). Statistically significant results are marked in bold.

BSc, Bachelor of Science; PharmD, Doctor of Pharmacy; MSc, Master of Science; PhD, Doctor of Philosophy.

* To streamline the analysis, the confidence levels were regrouped into three categories: “unconfident,” which includes “very unconfident” and “somewhat unconfident,” “neutral,” which remains unchanged, and “confident,” which includes “somewhat confident” and “very confident.” This adjustment maintains the inclusion of the neutral category while simplifying the analysis into three distinct confidence levels.

Table 5.

| Characteristic |

Comfortability level* |

Total | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncomfortable | Neutral | Comfortable | |||

| Gender | 0.098 | ||||

| Male | 3 (5.8) | 20 (38.5) | 29 (55.8) | 52 (100.0) | |

| Female | 22 (6.7) | 80 (24.3) | 227 (69.0) | 329 (100.0) | |

| Age groups (y) | 0.340 | ||||

| 23–30 | 22 (7.3) | 82 (27.3) | 196 (65.3) | 300 (100.0) | |

| 31–40 | 2 (3.6) | 10 (18.2) | 43 (78.2) | 55 (100.0) | |

| 41–50 | 1 (4.5) | 8 (36.4) | 13 (59.1) | 22 (100.0) | |

| >50 | 0 | 0 | 4 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | |

| Marital status | 0.373 | ||||

| Single | 19 (8.6) | 61 (27.6) | 141 (63.8) | 221 (100.0) | |

| Married | 5 (3.3) | 37 (24.3) | 110 (72.4) | 152 (100.0) | |

| Divorced | 1 (14.3) | 2 (28.6) | 4 (57.1) | 7 (100.0) | |

| Widow | 0 | 0 | 1 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) | |

| Do you have any children? | 0.249 | ||||

| No | 21 (7.9) | 70 (26.4) | 174 (65.7) | 265 (100.0) | |

| Yes | 4 (3.4) | 30 (25.9) | 82 (70.7) | 116 (100.0) | |

| Education level | 0.423 | ||||

| BSc | 16 (6.8) | 56 (23.9) | 162 (69.2) | 234 (100.0) | |

| PharmD | 5 (5.2) | 27 (28.1) | 64 (66.7) | 96 (100.0) | |

| MSc | 4 (10.3) | 11 (28.2) | 24 (61.5) | 39 (100.0) | |

| PhD | 0 | 6 (50.0) | 6 (50.0) | 12 (100.0) | |

| Work location | 0.178 | ||||

| Urban (city) | 23 (7.8) | 78 (26.4) | 194 (65.8) | 295 (100.0) | |

| Rural (village) | 2 (2.3) | 22 (25.6) | 62 (72.1) | 86 (100.0) | |

| Do you have personal experience in breastfeeding?† | 0.721 | ||||

| No | 13 (7.6) | 43 (25.1) | 115 (67.3) | 171 (100.0) | |

| Yes | 12 (5.7) | 57 (27.1) | 141 (67.1) | 210 (100.0) | |

| Pharmacy type | 0.116 | ||||

| Independent pharmacy | 21 (7.5) | 79 (28.2) | 180 (64.3) | 280 (100.0) | |

| Chain pharmacy | 4 (4.0) | 21 (20.8) | 76 (75.2) | 101 (100.0) | |

| Years of practice (y) | 0.295 | ||||

| <5 | 22 (7.7) | 75 (26.2) | 189 (66.1) | 286 (100.0) | |

| ≥5 | 3 (3.2) | 25 (26.3) | 67 (70.5) | 95 (100.0) | |

| How frequently would you currently experience queries on medication use in breastfeeding (including multivitamins/nutritional supplements)? | 0.034 | ||||

| Seldom | 7 (12.7) | 17 (30.9) | 31 (56.4) | 55 (100.0) | |

| 1–2 per month | 6 (8.6) | 25 (35.7) | 39 (55.7) | 70 (100.0) | |

| 1–2 per week | 8 (6.3) | 29 (22.7) | 91 (71.1) | 128 (100.0) | |

| Daily | 4 (3.1) | 29 (22.7) | 95 (74.2) | 128 (100.0) | |

| How often do you ask women if the dispensed medications are for breastfeeding ladies? | 0.000 | ||||

| Never | 1 (33.3) | 0 | 2 (66.7) | 3 (100.0) | |

| Rarely | 7 (43.8) | 4 (25.0) | 5 (31.3) | 16 (100.0) | |

| Sometimes | 5 (5.7) | 32 (36.8) | 50 (57.5) | 87 (100.0) | |

| Very often | 5 (4.8) | 23 (22.1) | 76 (73.1) | 104 (100.0) | |

| Always | 7 (4.1) | 41 (24.0) | 123 (71.9) | 171 (100.0) | |

| How often do you consult a hard copy resource for breastfeeding women? | 0.038 | ||||

| Never | 4 (12.5) | 8 (25.0) | 20 (62.5) | 32 (100.0) | |

| Rarely | 11 (12.2) | 26 (28.9) | 53 (58.9) | 90 (100.0) | |

| Sometimes | 10 (6.9) | 34 (23.4) | 101 (69.7) | 145 (100.0) | |

| Very often | 0 | 21 (26.6) | 58 (73.4) | 79 (100.0) | |

| Always | 0 | 11 (31.4) | 24 (68.6) | 35 (100.0) | |

| How often do you consult an online resource for breastfeeding women? | 0.057 | ||||

| Never | 4 (19.0) | 8 (38.1) | 9 (42.9) | 21 (100.0) | |

| Rarely | 4 (7.0) | 11 (19.3) | 42 (73.7) | 57 (100.0) | |

| Sometimes | 6 (4.8) | 39 (31.0) | 81 (64.3) | 126 (100.0) | |

| Very often | 10 (8.6) | 27 (23.3) | 79 (68.1) | 116 (100.0) | |

| Always | 1 (1.6) | 15 (24.6) | 45 (73.8) | 61 (100.0) | |

| How often do you receive prescriptions for medications that are not recommended in breastfeeding? | 0.570 | ||||

| Never | 2 (11.8) | 3 (17.6) | 12 (70.6) | 17 (100.0) | |

| Rarely | 10 (9.3) | 26 (24.3) | 71 (66.4) | 107 (100.0) | |

| Sometimes | 11 (6.1) | 51 (28.5) | 117 (65.4) | 179 (100.0) | |

| Very often | 2 (3.6) | 16 (28.6) | 38 (67.9) | 56 (100.0) | |

| Always | 0 | 4 (18.2) | 18 (81.8) | 22 (100.0) | |

| Product label/patient information leaflet | 0.526 | ||||

| No | 9 (7.9) | 33 (28.9) | 72 (63.2) | 114 (100.0) | |

| Yes | 16 (6.0) | 67 (25.1) | 184 (68.9) | 267 (100.0) | |

| American Academy of Pediatrics and World Health Organization recommendations | 0.248 | ||||

| No | 21 (7.6) | 75 (27.3) | 179 (65.1) | 275 (100.0) | |

| Yes | 4 (3.8) | 25 (23.6) | 77 (72.6) | 106 (100.0) | |

| Books | 0.500 | ||||

| No | 19 (7.2) | 72 (27.4) | 172 (65.4) | 263 (100.0) | |

| Yes | 6 (5.1) | 28 (23.7) | 84 (71.2) | 118 (100.0) | |

| Articles | 0.136 | ||||

| No | 18 (6.6) | 79 (29.0) | 175 (64.3) | 272 (100.0) | |

| Yes | 7 (6.4) | 21 (19.3) | 81 (74.3) | 109 (100.0) | |

| Internet search engines/websites | 0.996 | ||||

| No | 9 (6.6) | 36 (26.5) | 91 (66.9) | 136 (100.0) | |

| Yes | 16 (6.5) | 64 (26.1) | 165 (67.3) | 245 (100.0) | |

| Other | 0.136 | ||||

| No | 24 (6.6) | 99 (27.2) | 241 (66.2) | 364 (100.0) | |

| Yes | 1 (5.9) | 1 (5.9) | 15 (88.2) | 17 (100.0) | |

Values are presented as number (the distribution relative to each row %). Statistically significant results are marked in bold.

BSc, Bachelor of Science; PharmD, Doctor of Pharmacy; MSc, Master of Science; PhD, Doctor of Philosophy.

* To simplify the analysis, the comfortability levels were regrouped into three categories: “uncomfortable,” which includes “very uncomfortable” and “somewhat uncomfortable,” “neutral,” which remains unchanged, and “comfortable,” which includes “somewhat comfortable” and “very comfortable.” This adjustment maintains the inclusion of the neutral category while simplifying the analysis into three distinct comfortability levels.