Validity and Reliability of the Korean Version of Neighborhood Physical Activity Questionnaire

Article information

Abstract

Background

Given that a substantial number of daily activities take place in neighborhoods, a convenient and effective method for measuring the physical activity of individuals is needed. Therefore, we tested the validity and reliability of the Korean version of the Neighborhood Physical Activity Questionnaire (K-NPAQ), which was developed through translation and back-translation of the NPAQ.

Methods

The K-NPAQ was administered twice, with a 1-week interval, to participants in the study who were recruited at a health promotion center. We assessed energy expenditure and compliance using an accelerometer and an activity diary. The Kappa statistic and Spearman correlation coefficient were used to evaluate the test-retest reliability of the K-NPAQ, and the Spearman rank correlation was used to assess the validity.

Results

Of the 122 participants, 43 were excluded owing to a lack of compliance. The Kappa values for all items that were used to assess walking or cycling within or outside the neighborhood were >0.424; 0.251-0.902 for 5 items related to the purpose of the physical activity; 0.232-0.912 for most items related to the number of times and the duration for each types of physical activity. The total energy expenditure and the energy expenditure in the neighborhood were significantly correlated with the K-NPAQ and the accelerometer, with correlation coefficients of 0.192-0.264.

Conclusion

The K-NPAQ is a valid and reliable tool for measuring physical activity in the neighborhood, and it can be used for individual education and counseling in order to augment physical activity in specific neighborhood environments.

INTRODUCTION

Obesity and decreased physical activity have been associated with cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, colorectal cancer, breast cancer, and premature death among both sexes, regardless of the etiology.1,2) Regular exercise with moderate-to-high intensity can reduce the incidence of obesity, prevent cardiovascular disease, increase life expectancy, and extend the life span without cardiovascular disease.3) Additionally, aerobic and muscular strength exercises performed at regular intervals have been associated with a significant reduction in the prevalence of psychological illnesses such as depression, anxiety, and panic disorders.4)

Given that a considerable proportion of the daily activities of an individual take place in the surrounding neighborhood, a number of studies have reported on the association between factors in the residential environment and physical activity.5) In areas where walking is favored, the number of people who exercise adequately and with the recommended intensity was higher, while the prevalence of obesity and senile depression was lower.6,7)

Although there have been a few physical activity questionnaires that discriminated the places between within and outside the neighborhood where walking or bicycling were performed, the exact amount of physical activity that took place within the neighborhood could not be calculated.8,9) Giles-Corti et al.10) presented and confirmed the reliability of the Neighborhood Physical Activity Questionnaire (NPAQ) for measuring walking and overall activity within the neighborhood. Thirty-five items were developed to measure the frequency and duration of walking and cycling within and outside the local neighborhood, to assess the specific place where the activity was performed, and to measure the frequency and duration of other physical activities. Adequate reliabilities were observed for all items among Australian, Canadian, and Belgian adults, and the validity of the walking components was satisfactory among elderly Chinese individuals.10,11,12,13)

This study was designed in order to develop a Korean version of the Neighborhood Physical Activity Questionnaire (K-NPAQ), which was related to the walkable environment of the neighborhood, to confirm both the validity and reliability of this tool.

METHODS

1. Translations of the Questionnaire

After receiving permission from the original NPAQ development team, we followed the standard methods for translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the questionnaires.14) Two highly educated translators who were fluent in both English and Korean translated the NPAQ into Korean. The research study group developed a single form using the cross-cultural adaptation procedures. Two native English speakers independently back translated the document, and the research group described the results in a single document. The original NPAQ development team then confirmed the similarity for the backward translated questionnaires with the original one.

2. Participants

Study volunteers who were 20 to 71 years of age were recruited from a health promotion center where healthy individuals underwent periodic health examinations and cancer screening tests. The exclusion criteria were the following: acute or chronic illnesses that interfered with physical activity, and night shift workers who were expected to perform irregular daytime activities.

The NPAQ development study enrolled 121 participants, and the test-retest reliability analysis was performed on 82 subjects.10) Assuming a correlation coefficient of 0.4 to 0.6 between the assessment tool and the actual physical activity measurement, and considering a drop-out rate of 35%, an α error of 0.05, and a β error of 0.1, the number of participants needed for the study was calculated using the following equation:

3. Study Design and Measures

The K-NPAQ was administered to participants with an interviewer-assisted self-report questionnaire. The neighborhood was defined as all areas that were within a 10 to 15 minutes walk from the home of the participant. For the test-retest reliability analysis, the same questionnaire was also administered 7 days later.

Physical activity on the K-NPAQ was divided into walking for transport (2.5 metabolic equivalents, MET), walking for recreation/health (3.5 MET), cycling for transport (6.8 MET), cycling for recreation/health (8.0 MET), other moderate activity during leisure time (4.0 MET), and vigorous activity during leisure time (8.0 MET), based on the previous compendium.16) The location where the activities were performed was divided into 'neighborhood' and 'at a distance,' and the list of behavior-specific destinations was provided. The energy expenditure (kcal/6 days) for specific types of physical activities and the total energy expenditure (TEE) were calculated. The TEE was calculated based on the sum of all activities including both moderate and vigorous, regardless of the place where the activities were performed. The neighborhood energy expenditure (NEE) was calculated only using walking and cycling within the neighborhood, as the questionnaire did not distinguish between locations for moderate and vigorous activities.

An accelerometer (Lifecorder, Kenz, Japan) was used to assess the TEE and NEE over 6 consecutive days. The Lifecorder is a uniaxial accelerometer that has been used to precisely assess physical activity.17,18,19) The participants were instructed to wear the Lifecorder upon awakening in the morning and to remove it just before going to bed at night. Additionally, a self-administered activity log was recorded for 6 days in which the time of awakening, sleeping, and entering or exiting the neighborhood was documented.

Physical activity measured by the accelerometer was calculated in terms of the TEE, total hours of activity over 6 days, the NEE, and hours of activity in the neighborhood using raw data derived from the instrument and the activity log. The intensity of the activity was expressed as grades 0-9, with the Lifecorder representing 0, <1.8, 2.3, 2.9, 3.6, 4.3, 5.2, 6.1, 7.1, and 9.1 MET, respectively.19) Grades 0 was not counted as actual physical activity. Grades 1-3 were designated as mild, grades 4-6 as moderate, and grades 7-9 as vigorous activity. The total activity time was defined based on the activity log as the total hours, with the exception of sleeping hours, over 6 consecutive days.

Compliance was considered to be good when the total activity time was >96 hours and when the accelerometer was worn for >70% of the total activity time. Participants who were poorly compliant with respect to the accelerometer and those who did not complete the second K-NPAQ were excluded from the analysis.

4. Statistics

Test-retest reliability was assessed using the Kappa value and the percent agreement for dichotomous variables. The Spearman correlation coefficient was used for continuous variables after an examination for a normal distribution showed that every data set had skewed deviations. The degree of agreement was defined as slight agreement (<0.2), fair (0.2-0.4), moderate (0.4-0.6), substantial (0.6-0.8), and almost perfect (>0.8), based on the Kappa value and the Spearman correlation coefficient.20)

The Spearman rank correlation was used to assess the validity of the K-NPAQ by comparing the level of daily activity from the initial K-NPAQ data with the actual energy expenditure data from the accelerometer, which was regarded as the gold standard. The statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS ver. 22.0 for Windows (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA).

5. Ethics Statement

The study volunteers provided written informed consent. This study protocol was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of Seoul National University Hospital (IRB approval No. H-0809-098-258).

RESULTS

1. Characteristics of the Study Subjects

Of a total of 122 subjects who were enrolled in the study, 43 were excluded from the analysis owing to either missing the second questionnaire (n=22) or a lack of compliance with the accelerometer (n=38). Thus, 79 subjects were included in the statistical analysis. The number of subjects for each analysis differed with respect to the different response rates to each of the items.

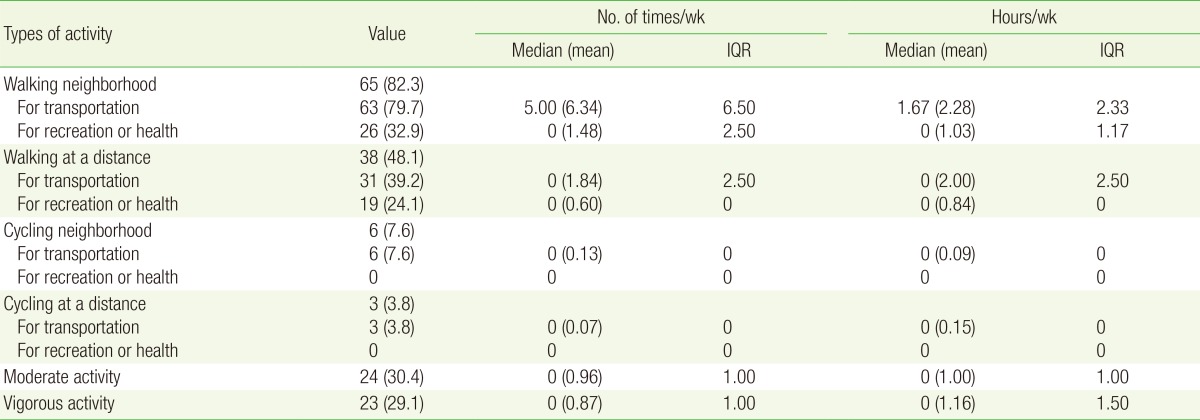

Among the respondents, 53.2% answered that they exercised regularly and 24.1% of the participants had at least one chronic metabolic disease (Table 1). Among the different types of physical activities, walking in the neighborhood for transportation had the highest frequency (79.7%), with median values of 5 times and 1.67 hours per week. In terms of the other types of physical activity, less than half of the participants answered that they typically performed these activities (Table 2).

None of the subjects reported cycling for recreation within or outside the neighborhood. Normal distributions were observed for the total activity time, hours of wearing the accelerometer, TEE, and TEE with mild intensity. However, skewed deviations were observed for the other variables (Table 3).

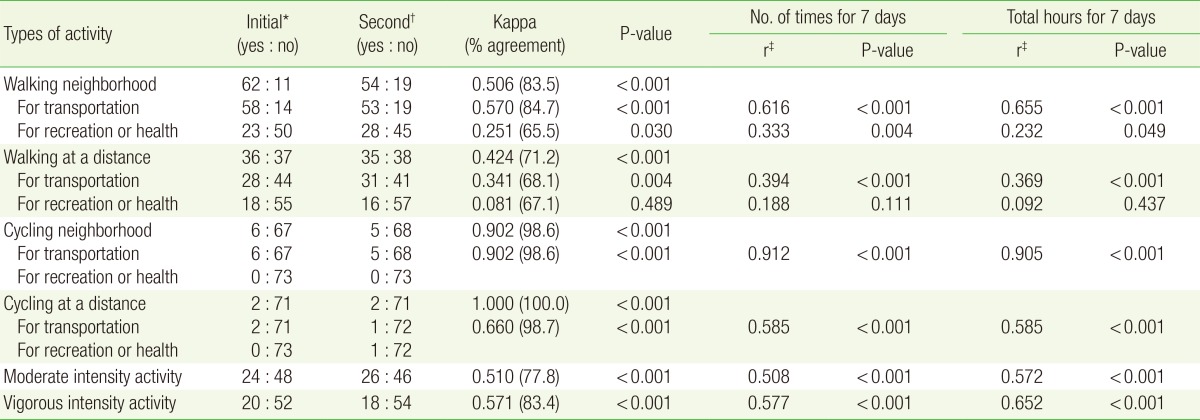

2. Reliability

The Kappa values for items that assessed walking in the neighborhood, walking at a distance, cycling in the neighborhood, cycling at a distance, moderate activity, and vigorous activity were >0.424, which was indicative of a moderate correlation. Items regarding the purpose of physical activity had different levels of reliability: there was a moderate correlation with walking in the neighborhood for transport, a fair correlation with walking in the neighborhood for recreation/health and walking at a distance for transport, no significant correlation with walking at a distance for recreation/health, and a substantial to almost perfect correlation with cycling for transport. The Kappa values were not calculated for cycling for recreation/health (Table 4).

Items regarding cycling in the neighborhood for transport showed almost perfect agreement with both the number of times the activities were performed and the duration. Items regarding walking in the neighborhood for transport were substantially correlated, while cycling at a distance for transport, moderate activity, and vigorous activity were only moderately correlated with both the number of times the activities were performed and the duration. Items regarding walking in the neighborhood for recreation and walking at a distance for transport were fairly in agreement with both the number of times the activities were performed and the duration. Analysis of cycling for recreation was not performed (Table 4).

All items regarding the usual places of walking in the neighborhood for transport showed moderate-to-good agreement with the Kappa values (0.450-0.793). Items for the places of walking in the neighborhood for recreation, the Kappa values were significant for the beach/lakeshore (0.412) and shopping (0.225) items. For walking at a distance for transport, work (0.332), a friend's house (0.412), public transport (0.359), and shopping (0.274) were statistically significant. For walking at a distance for recreation, only the sidewalk (0.793) was significant. For cycling in the neighborhood for transport, only shopping (0.66) was significant. Finally, for cycling at a distance for transport, no items showed statistically significant agreement (data not shown).

3. Validity

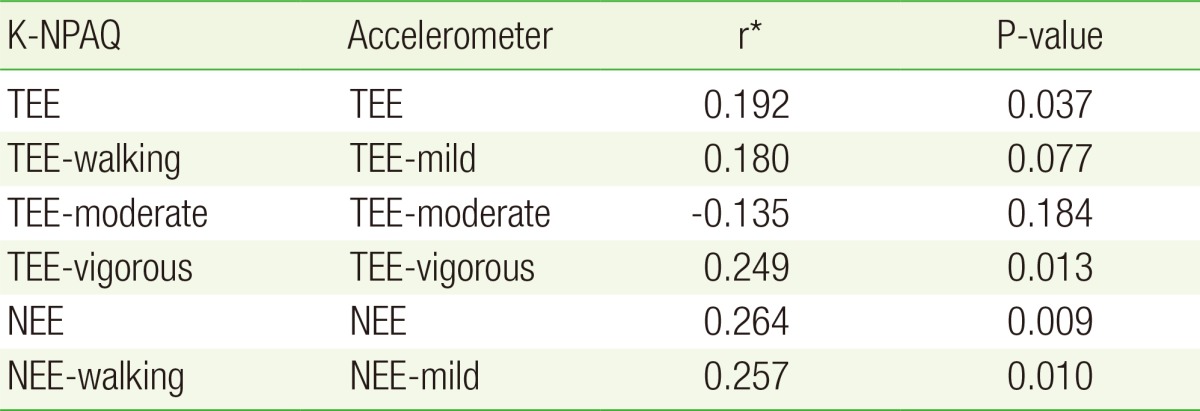

The TEE, TEE-vigorous, NEE, and energy expenditure calculated for walking in the neighborhood were statistically significant but showed poor agreement with the accelerometer (correlation coefficient 0.192-0.264, P<0.05), whereas the other variables did not show statistically significant agreement with the Spearman rank correlation (Table 5).

4. Activity Distribution from the Accelerometer

The NEE was 60.4% of the TEE. Mild, moderate, and vigorous intensity NEE accounted for 61.6%, 55.6%, and 66.7% of the TEE, respectively. The neighborhood activity time was 42.6% of the total activity time. Mild intensity activity was responsible for 74.4% of the TEE and 75.8% of the NEE, moderate intensity activity accounted for 22.4% of the TEE and 20.6% of the NEE, and vigorous intensity activity accounted for 3.2% of the TEE and 3.5% of the NEE.

DISCUSSION

This study was performed in order to develop the K-NPAQ as a convenient and efficient tool for measuring physical activities around the neighborhood, and to assess the reliability and validity of this questionnaire. Among various types of physical activity, mild intensity activity within the residential area such as walking around the neighborhood has significant implications for total daily activities among many Korean individuals. A survey of health behaviors performed by the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey showed that the preferred exercises were walking, mountain hiking or climbing, jogging, and fitness. The results indicated that 60.7% of individuals who performed regular exercise chose walking as their exercise.21) Among our study participants, 90% reported that they walked for transport or recreation inside or outside the neighborhood. Only a small number of individuals participated in bicycling, 6 of who biked for transport within the neighborhood, 2 for transport at a distance, and none for recreation and/or fitness. Additionally, although the time spent around the neighborhood was 42.6% of the total activity time, the amount of neighborhood physical activity was around 60% of the total, with mild intensity activity accounting for 75% of the total activity.

The energy expenditure calculated with the K-NPAQ was only 23.1% to 45.2% of the actual energy expenditure measured with the accelerometer for most activity intensities, with the exception of vigorous activity. These results were similar to the outcomes reported in previous studies.22,23) Daytime activities such as housework and standing/riding in cars were not included in the questionnaire. Some events may have been omitted owing to recall bias. The actual METs could have been higher than those reported in the compendium. Some participants answered that they were performing vigorous exercise aside from the measured data.

In conclusion, we have confirmed the validity and reliability of the K-NPAQ for the assessment of mild intensity physical activity within the neighborhood, which accounts for the large amount of typical daytime physical activity. In addition to assessing and encouraging physical activity among individuals, the K-NPAQ may also contribute to the design of new instruments for the investigation of walkable surroundings, which could support public health and city planning activities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Research Settlement Fund for new faculty at Seoul National University.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.