|

|

- Search

| Korean J Fam Med > Volume 36(6); 2015 > Article |

Abstract

Background

Fast eating or overeating can induce gastrointestinal diseases such as gastritis. However, the association between gastritis and speed of eating is unclear. The aim of this study was to determine whether eating speed is associated with increased risk of endoscopic erosive gastritis (EEG).

Methods

We carried out a cross-sectional study involving 10,893 adults who underwent a general health checkup between 2007 and 2009. Two groups, EEG patients and EEG-free patients, were compared by using the t-test and the chi-square test. Multiple logistic regression analyses were performed to investigate the association between eating speed and EEG.

Results

The group with EEG had a higher proportion of males, average age, body mass index, and percentages of current smokers and risky drinkers than those without EEG. After adjusting for anthropometric, social, and endoscopic parameters, the group with the highest eating speed (<5 min/meal) had 1.7 times higher risk for EEG than the group with the lowest eating speed (≥15 min/meal) (odds ratio, 1.71; 95% confidence interval, 1.20-2.45).

Erosive gastritis is caused by damage to the gastric mucosa with a depressed area due to erosion on the hemispheric nodule. Although the pathophysiology of erosive gastritis has not been clarified yet, it is thought to occur because of an imbalance between the defenses of the stomach wall and offensive factors in the stomach. The defenses of the stomach wall include mucus, bicarbonate, tissue regeneration ability, and mucosal blood flow, while the offensive factors include gastric acid, pepsin, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, alcohol, and Helicobacter pylori.1)

Studies have reported a higher prevalence of digestive diseases with mucosal lesions such as erosive gastritis, gastric ulcer, and duodenal ulcer among those with a relatively higher body mass index (BMI).2,3) High eating speed and overeating are likely to be related to gastrointestinal diseases such as gastritis. Those who eat faster tend to feel less satiated than those who eat slower and, consequently, tend to eat more.4) Overeating causes food to stay in the stomach longer; this means that the gastric mucosa is exposed to gastric acid for longer durations. Thus, the likelihood of gastrointestinal diseases increases.5) Despite the likelihood of high eating speed causing digestive diseases through this mechanism, to our knowledge, no study has been conducted as yet to examine the relationship.

The present study aimed to determine the association between high eating speed and endoscopic erosive gastritis (EEG) among subjects coming to a health center for a general health checkup.

This cross-sectional study was conducted on 12,593 participants who had undergone regular health checkups between March 1, 2007 and March 31, 2009 at a health promotion center in Korea University Anam Hospital. The study participants underwent physical examination, including esophagogastroduodenoscopy, and filled a questionnaire on smoking, drinking, and eating speed. Subjects who did not undergo endoscopy (n=1,692) and whose endoscopic biopsy examination revealed cancer (n=8; seven gastric adenocarcinomas and one esophageal squamous cell carcinoma) were excluded from the study, resulting in the final total of 10,893 participants. All participants gave written informed consent, and the study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the Korea University Anam Hospital (IRB No. AN09141-001).

Height and weight were measured with the participants in light-weight clothes and stocking feet. All participants filled out a structured, self-report questionnaire through which data were collected on disease history; medication history; sociodemographic factors such as sex, age, education level, marital status, and occupation; and lifestyle factors such as smoking and drinking habits and physical activity. Risky drinking was defined as an average daily alcohol consumption of >20 g.

A registered dietitian examined the dietary habits of the participants in one-on-one interviews. The amount and frequency of food intake was examined via a food frequency questionnaire. Eating speed was classified into four categories according to the self-reported time taken to complete a meal: (1) <5 minutes, (2) 5-10 minutes, (3) 10-15 minutes, and (4) ≥15 minutes.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (GIF-H260; Olympus Optical Co., Tokyo, Japan) was performed by two gastroenterologists, each of whom had over 5 years of endoscopic experience with over 10,000 cases. Endoscopic diagnoses included 'reflux esophagitis,' 'Barrett esophagus,' 'hiatal hernia,' 'atrophic gastritis,' 'superficial gastritis,' 'erosive gastritis,' 'intestinal metaplasia,' 'gastric ulcer,' 'duodenal ulcer,' 'duodenitis,' 'stomach polyps,' and 'submucosal tumor.' Finally, another experienced endoscopist reexamined the endoscopic photographs to confirm the diagnoses.

An 'erosion' was defined as a flat or slightly depressed white lesion surrounded by a red wall or accompanied by small surface bleeding.6) 'Erosive gastritis' was diagnosed when gastritis with erosion was seen at endoscopy. Infection with H. pylori was determined by the cresyl-violet staining of mucosal tissue or with a urea breath test.

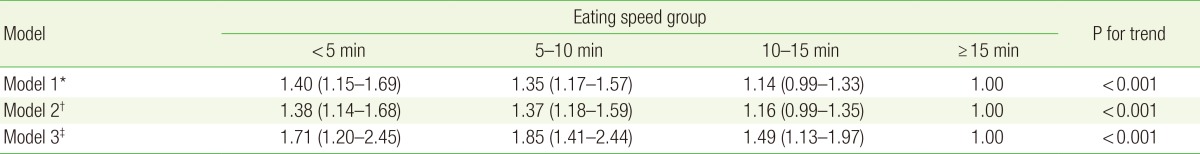

The EEG group and EEG-free group were compared in terms of clinical characteristics, lifestyle factors, eating speed, and endoscopic findings using the t-test and the chi-square test. The relationship between eating speed and erosive gastritis was examined with logistic regression analysis. Variables that were significantly associated with erosive gastritis in the univariate analysis (P<0.05) were included as covariates in multivariate analysis. In model 1, sex, age, and BMI were included as covariates, and in model 2, current smoking and risky drinking were included in addition to the covariates in model 1. In model 3, the covariates included reflux esophagitis, atrophic gastritis, gastric ulcer, duodenal ulcer, duodenitis, and H. pylori infection in addition to the covariates of model 2. For the trend analysis, eating speed as a continuous variable was applied to the logistic regression model. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS ver. 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and a two-sided P-value <0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

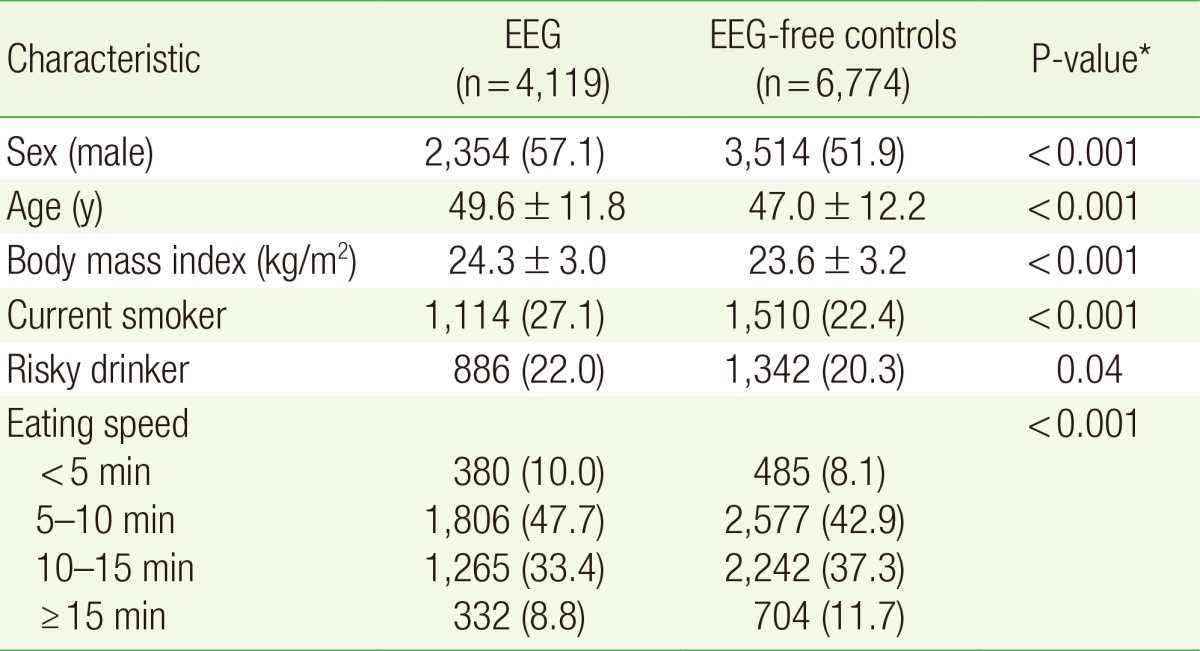

The general characteristics of the subjects are shown in Table 1. In all, 4,119 (37.8%) of the 10,893 subjects were found to have EEG. The EEG group had a higher proportion of men and higher average age and BMI than the EEG-free group (P<0.001). The proportions of current smokers and risky drinkers were higher in the EEG group (P<0.05) as also the proportion of those who reported high eating speeds (P<0.001).

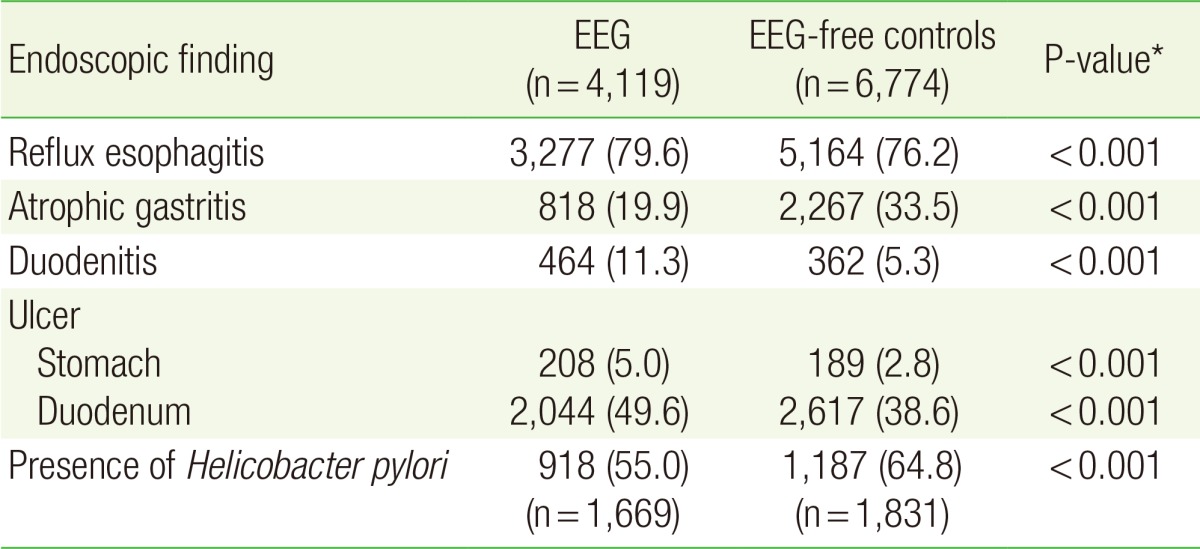

Endoscopic findings other than erosive gastritis were compared between the EEG group and the EEG-free group (Table 2). The EEG group showed higher prevalence of reflux esophagitis, duodenitis, gastric ulcer, and duodenal ulcer than the EEG-free group (P<0.001), but lower prevalence of atrophic gastritis and H. pylori infection (P<0.001).

In all three models, subjects with an eating speed < 5 minutes and 5-10 minutes showed a higher risk of EEG than those with an eating speed ≥15 minutes (Table 3). In model 3, in which all possible confounding variables were included, the risk of EEG increased as the eating speed increased (P for trend <0.001), with the risk being 71% higher among subjects with an eating speed of <5 minutes compared to those with an eating speed of ≥15 minutes (odds ratio, 1.71; 95% confidence interval, 1.20-2.45).

This study examined the association between eating speed and EEG. The results showed that high eating speed was associated with increased risk of EEG. It was found to be an independent risk factor for EEG, even after adjusting for variables such as BMI, lifestyle, and other endoscopic findings.

To explain the association between high eating speed and increased risk of EEG, the following mechanisms can be considered. The first is the possibility that the gastric mucosa is damaged due to the increased time during which food remains in the stomach. Those who eat fast are likely to chew the food less in terms of the number of chews before swallowing and the total time spent chewing.7) Since the stomach is exposed to gastric acid for a longer time because of the time for which food remains in it, the likelihood of damage to the mucosa also increases.5) The second possibility is the increased likelihood of overeating when eating fast. Those who eat fast are often under psychological stress, which increases cortisol levels, thereby regulating homeostasis and metabolism of the body, and leading to overeating.8) In addition, fast eating can lead to overeating because reduced exposure to gustatory, olfactory, and visual stimuli can result in delayed satiety.4) Fast eating may also cause less satiety by slowing down the reactions of peptide YY or glucagon-like peptide 1, which suppress appetite.9)

Examination of the relationship between EEG and the other endoscopic findings shows a higher prevalence of reflux esophagitis, duodenitis, gastric ulcer, and duodenal ulcer among patients with EEG than among the EEG-free group. Since reflux esophagitis, duodenitis, gastric ulcer, and duodenal ulcer are closely related to gastric acid exposure, the possibility that gastric acid plays an important role in the genesis of EEG should be considered.10)

The relationship between H. pylori infection and EEG is currently unclear. It has been reported that H. pylori infection independently increases the risk of erosive lesions such as gastric ulcer as well as of ulcerative bleeding.11) On the other hand, it has also been reported that subjects with erosive gastritis and chronic gastritis showed no significant difference compared to controls in terms of H. pylori infection rates.12) In the present study, the H. pylori infection rate was relatively higher in the subjects without erosive gastritis. In acute H. pylori infection, increased somatostatin and reduced histamine secretion causes suppression of gastric acid secretion.13) Similarly, in chronic H. pylori infection, the atrophy of gastric mucosa that is seen in most patients causes reduced gastric acid secretion.14,15) Therefore, it may be concluded that erosive gastritis resulting from excessive gastric acid and H. pylori infection are negatively associated. The high prevalence of atrophic gastritis among subjects without erosive gastritis in this study may also be attributable to H. pylori infection. However, the results should be interpreted cautiously, given that this study was conducted on subjects coming for routine health checkups and, in this group, it is likely that the H. pylori test was performed selectively in those with known gastric lesions such as gastroduodenal ulcers or atrophic gastritis rather than in randomly selected subjects.

This study has several limitations. First, this study used data collected from individuals who participated in health checkups and, therefore, it is difficult to generalize the study results to the general population. Second, due to the nature of the checkup, endoscopic biopsy was performed only on selected patients and, any interpretation of the H. pylori infection rates is therefore of limited value. Third, the measurement of the eating speed was based on self-reported estimate of the duration of the meal consumption and, as such, its accuracy can be questioned. For example, those with functional gastrointestinal diseases may have underreported the length of their meal consumption because of the widespread belief among Koreans that fast eating is not good for digestion. Fourth, because this is a cross-sectional study, the temporal association between high eating speed and erosive gastritis is unclear and therefore causality cannot be established.

In conclusion, high eating speed was found to be associated with an increased risk of EEG. Prospective studies and further research on the mechanisms that may be involved are needed to identify the specific role of high eating speed in the development of gastritis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Korea University Anam Hospital Health Promotion

Center for data collection and management.

References

1. DeFoneska A, Kaunitz JD. Gastroduodenal mucosal defense. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2010;26:604-610. PMID: 20948371.

2. Kim HJ, Yoo TW, Park DI, Park JH, Cho YK, Sohn CI, et al. Influence of overweight and obesity on upper endoscopic findings. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;22:477-481. PMID: 17376036.

3. Garrow D, Delegge MH. Risk factors for gastrointestinal ulcer disease in the US population. Dig Dis Sci 2010;55:66-72. PMID: 19160043.

4. De Graaf C, Kok FJ. Slow food, fast food and the control of food intake. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2010;6:290-293. PMID: 20351697.

5. Zhang HF, Xue YW. Empirical study in the relation of gastric mucosal lesion with gastric emptying and gastric acid secretion. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi 2008;11:472-476. PMID: 18803054.

6. Yamamoto S, Watabe K, Tsutsui S, Kiso S, Hamasaki T, Kato M, et al. Lower serum level of adiponectin is associated with increased risk of endoscopic erosive gastritis. Dig Dis Sci 2011;56:2354-2360. PMID: 21448696.

7. Ekuni D, Furuta M, Takeuchi N, Tomofuji T, Morita M. Self-reports of eating quickly are related to a decreased number of chews until first swallow, total number of chews, and total duration of chewing in young people. Arch Oral Biol 2012;57:981-986. PMID: 22381534.

8. Torres SJ, Nowson CA. Relationship between stress, eating behavior, and obesity. Nutrition 2007;23:887-894. PMID: 17869482.

9. Kokkinos A, le Roux CW, Alexiadou K, Tentolouris N, Vincent RP, Kyriaki D, et al. Eating slowly increases the postprandial response of the anorexigenic gut hormones, peptide YY and glucagon-like peptide-1. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:333-337. PMID: 19875483.

10. Malfertheiner P, Chan FK, McColl KE. Peptic ulcer disease. Lancet 2009;374:1449-1461. PMID: 19683340.

11. Huang JQ, Sridhar S, Hunt RH. Role of Helicobacter pylori infection and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in peptic-ulcer disease: a meta-analysis. Lancet 2002;359:14-22. PMID: 11809181.

12. Kate V, Ananthakrishnan N, Badrinath S, Amarnath SK, Balamurugan M, Ratnakar C. Helicobacter pylori infection and erosive gastritis. J Assoc Physicians India 1998;46:436-437. PMID: 11273284.

13. Zaki M, Coudron PE, McCuen RW, Harrington L, Chu S, Schubert ML. H. pylori acutely inhibits gastric secretion by activating CGRP sensory neurons coupled to stimulation of somatostatin and inhibition of histamine secretion. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2013;304:G715-G722. PMID: 23392237.

14. El-Omar EM. Mechanisms of increased acid secretion after eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection. Gut 2006;55:144-146. PMID: 16407378.

15. El-Omar EM, Oien K, El-Nujumi A, Gillen D, Wirz A, Dahill S, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and chronic gastric acid hyposecretion. Gastroenterology 1997;113:15-24. PMID: 9207257.

Table 3

Odds ratios (and 95% confidence intervals) for endoscopic erosive gastritis according to eating speed

Values are presented as odds ratios (95% confidence intervals).

*Adjusted for sex, age, and body mass index. †Adjusted for all covariates in model 1, plus current smoking and risky drinking (average daily alcohol consumption of >20 g). ‡Adjusted for all covariates in model 2, plus reflux esophagitis, atrophic gastritis, gastric ulcer, duodenal ulcer, duodenitis, and the presence of Helicobacter pylori.