INTRODUCTION

Thyroid eye disease (TED) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the eye that can occur in patients with systemic thyroid disorder. It is the most common cause of bilateral and unilateral proptosis with a female preponderance and peak incidence in the 5th decade of life.1) Although thyroid ophthalmopathy is not uncommon, its pathogenesis has not been thoroughly studied and remains unclear. A consistent pathogenic link between Graves' disease and ophthalmopathy has yet to be identified.2) The pathogenesis involves immunoglobulin G antibody and an organ-specific autoimmune reaction. T-cell lymphocytes and thyroid follicular cells with shared antigenic epitopes are thought to react in the retro-orbital space. Sight-threatening compressive optic neuropathy is one of the most feared complications of thyroid ophthalmopathy. However, the occurrence of optic neuropathy is rare and constitutes about 4% to 8% of all complications.3,4) Management of thyroid eye disease is based on the consensus statement produced by the European Group on Graves' Orbitopathy. Thyroid eye disease is usually self-limiting; its frequency is declining; and 3% to 5% cases are sight threatening.5) Treatment for Graves' disease is directed towards alleviating symptoms, managing hyperthyroidism, and addressing issues such as smoking and other aggravating factors. The following cases illustrate the atypical and subtle presentations of sight-threatening thyroid eye disease that can be missed during an initial visit. They also illustrate the worsening of thyroid eye disease and its relationship to radioactive iodine (RAI) therapy.

CASE REPORTS

1. Case 1

A 67-year-old Malay man presented with gradual onset of bilateral eye redness and tearing for 2 months after receiving a second RAI therapy for thyrotoxicosis without oral steroid coverage. He was treated for dry eyes 2 months prior to presentation.

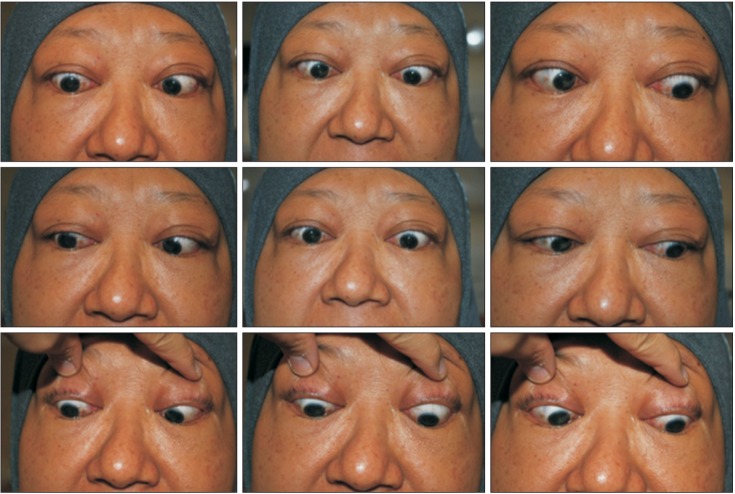

Upon presentation, ocular examination revealed a poor visual acuity of 6/60 and N24 bilaterally with an absence of relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD). Extraocular muscle examinations revealed generalized restriction in all positions of gaze particularly on downgaze (Figure 1). Anterior segment examination of both eyes revealed fullness and redness of the eyelids, both of which appeared ptotic. Conjunctival injection and chemosis, as well as caruncle swelling and redness were also present. There was no evidence of proptosis. Both eyes, however, were dry with superficial punctate keratopathy of the cornea. There were minimal nuclear sclerosis cataracts present bilaterally and intraocular pressures were normal in both the primary gaze and upgaze. The exophthalmometer measurements were 19 mm. Fundus examination revealed normal looking optic discs and no disc swelling. Clinical findings indicated signs of active TED with a Mourits activity score of 5/7.

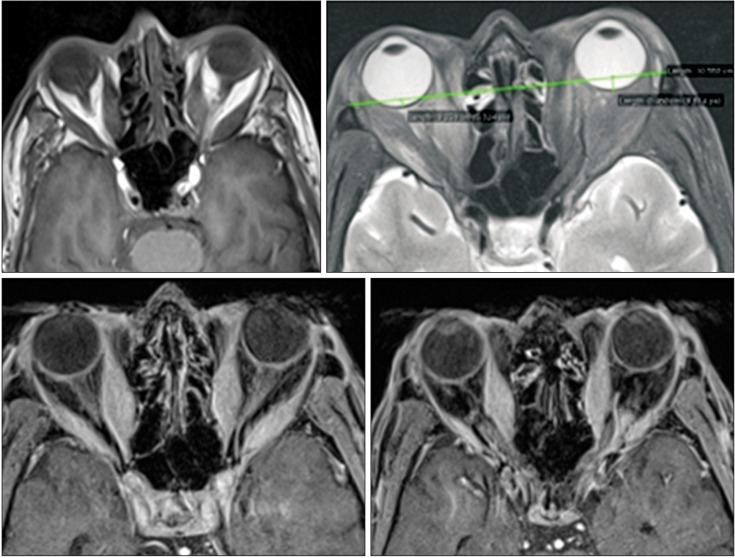

Further color vision, Hess chart, Binocular single vision, and Bjerrum visual fields tests were performed, all of which revealed a derangement of color vision with D15 testing and constricted visual fields consistent with aspects of compressive optic neuropathy in both eyes. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the orbit (Figure 2) revealed crowding of the orbital apex consistent with thyroid ophthalmopathy. A thyroid function test revealed that the patient, although taking oral thyrosine, was biochemically hypothyroid.

The patient was admitted, and a regimen of high-dose pulse intravenous methylprednisolone was commenced. After the fourth week of treatment, his visual acuity improved to 6/9 bilaterally, and a gradual resolution of the clinical signs and symptoms of thyroid eye disease was noted (Figure 3).

2. Case 2

A 48-year-old Malay woman presented with diplopia on upward gaze for 2 months following RAI therapy without oral steroid coverage for her thyrotoxicosis. She was newly diagnosed with thyrotoxicosis 4 months prior to the RAI therapy.

Upon presentation, ocular examination of the right eye revealed a visual acuity of 6/36, 6/12 with a pinhole occluder, and a near vision of N36, while examination of the left eye revealed a visual acuity of 6/12 with a pinhole occluder and a near vision of N6. There was grade 1 RAPD over the left eye with positive red desaturation. Both eyes appeared proptosed, and extra-ocular muscle examination revealed restrictions in all gaze positions, especially in the upgaze (Figure 4). There was periorbital swelling and lid retraction. Redness of the eyelid was not present. Anterior segment examination revealed conjunctiva chemosis and injection particularly at the site of recti-muscle insertion. Both eyes were dry with superficial punctate keratopathy more marked at inferior cornea. Nuclear sclerosis cataracts affecting the patient's vision were present bilaterally, and were more pronounced over the right eye. Her intraocular pressures (IOP) were high in both the primary gaze and upgaze. The exophthalmometer measurements were 20 mm. Fundus examination revealed a slightly hyperemic and swollen superior edge of the right optic disc, while the optic disc over the left eye was normal.

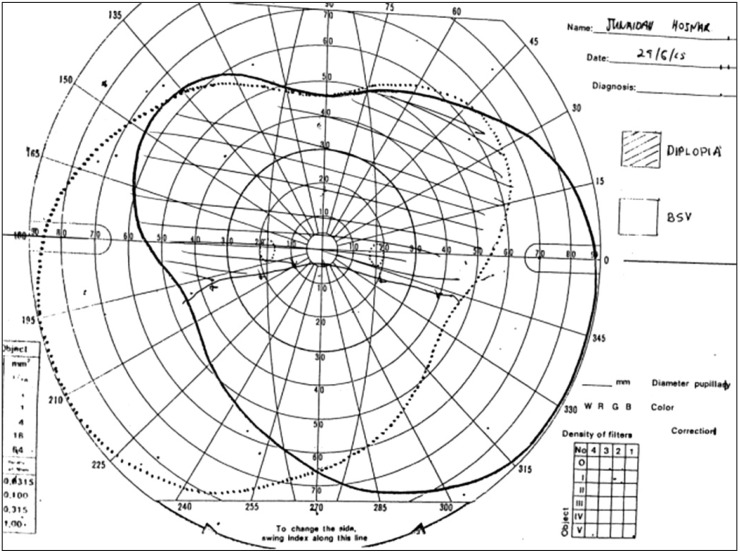

Binocular single vision testing revealed diplopia at all gazes except the inferior gaze (Figure 5). Hess chart, color vision, and Bjerrum visual field tests were normal. Computed tomography of the orbit with contrast showed a crowding of the right orbital apex with hypertrophy of all the extraocular muscles. These results are consistent with thyroid ophthalmopathy. Considering the clinical evidence for optic neuropathy, the patient was admitted and pulsed with a high dose of intravenous methylprednisolone.

DISCUSSION

Treatment of hyperthyroidism is associated with the development or progression of ophthalmopathy. Therefore, detection of this condition during clinical examination is highly important so that it can be efficiently managed.

Progression of ophthalmopathy was more common in patients treated with RAI than in those who received anti-thyroid drugs or surgery.1,6) One study proposed that the development or progression of ophthalmopathy after RAI therapy may be related to the release of thyroid antigens as a result of radiation injury and to the subsequent enhancement of autoimmune responses directed toward antigens shared by the thyroid and orbit.7) RAI for Graves' hyperthyroidism was followed by the development, or more often, the progression of ophthalmopathy in patients treated with RAI alone, but not in those treated with RAI and prednisolone.8) In these two cases, both patients were not administered oral steroids prior to or during RAI therapy.

In case 1, the patient's eyes appeared not proptosed, but ptotic. Nevertheless, he had active and sight-threatening thyroid eye disease. There was evidence of optic neuropathy confirmed by constriction of the visual field, and MRI of the orbit showed crowding of the orbital apex due to enlargement of the extraocular muscles. This pathogenesis is due to the accumulation of glycosaminoglycans, which leads to a retention of water, increasing the intraorbital soft tissue volume and pushing the eye forward, resulting in proptosis. Therefore, the absence of proptosis in active TED increases the risk of optic nerve compression, because the swollen soft tissue within the confined space of the orbit prevents forward decompression of the optic nerve. Diagnosis of optic nerve dysfunction might be missed if there is no obvious proptosis as highlighted in case 1.9) It also stated that an increase in orbital pressure will precipitate dysthyroid optic neuropathy when there is lack of proptosis. The lack of RAPD detection may suggest that there was equal and bilateral involvement of the optic nerves by compression. In case 2, both eyes appeared proptosed and there was grade 1 RAPD over the left eye with secondary high IOP in both eyes. These cases illustrate the importance of good clinical skills. The subtle signs of optic neuropathy must be detected quickly, so that a treatment plan can be initiated to prevent further vision loss.

Both patients were treated with 500 mg pulse intravenous methylprednisolone for 6 weeks and then 250 mg once weekly for another 6 weeks (total period of 12 weeks with total dose of 4,500 mg). This treatment regime was adapted according to the recommendation by Kahaly et al.10) In patients receiving radiotherapy for TED, modifying the treatment can slow the development of ophthalmopathy.2) The administration of glucocorticoids prior to RAI is generally expected to limit the progression of ophthalmopathy.11)

In conclusion, active thyroid eye disease often presents as pseudoptosis instead of the classical lid retraction with 'starry' gaze (Kocher sign). Physicians need to be aware of this atypical presentation. Although RAI therapy is one of the primary treatment modalities for TED, it can also have a disastrous effect on the vision. Therefore, it is imperative for the patient to be administered glucocorticoids prior to treatment with RAI for hyperthyroidism. Family medicine practitioners and physicians need to anticipate the possibility for the development or worsening of thyroid eye disease post-RAI treatment, as timely intervention can prevent the vision loss that results from compressive optic neuropathy in active thyroid eye disease.