Carbohydrate-Deficient Transferrin as a Biomarker for Screening At-Risk Drinking in Elderly Men

Article information

Abstract

Background

Carbohydrate-deficient transferrin (CDT) is a useful biomarker to identify excessive alcohol consumption; however, few studies have validated the %CDT cut-off value in elderly men. This study estimated the optimal %CDT cut-off value that could identify excessive alcohol consumption in men aged ≥65 years.

Methods

This retrospective study included 120 men who visited the department of family medicine at Chungnam National University Hospital for health check-up between January 2010 and August 2013. At-risk drinking included heavy- and binge drinking. Heavy drinking was defined as more than seven standard drinks/wk, and binge drinking was defined as more than three standard drinks/d. The cut-off %CDT values for at-risk drinking were determined using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves.

Results

Based on the ROC curves, the optimal %CDT cut-off values in ≥65-year-old men were 1.95% for at-risk drinking, 1.81% for heavy drinking, and 2.07% for binge drinking. The sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values were 58.7%, 83.6%, 69.2%, and 76.2% for at-risk drinking, respectively. The AUROC were >0.7 for all three evaluated cut-offs.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that the %CDT cut-off value for at-risk drinking in elderly Korean men (≥65 years) should be readjusted to a lower value of 1.95%.

INTRODUCTION

The screening of excessive alcohol consumption in a primary care setting utilizes a brief, simple set of questions such as the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test for Consumption: a screening test comprising three items on excessive alcohol consumption. While not ideal, other screening tools such as laboratory tests can also be utilized to detect unhealthy alcohol use in settings where routine questionnaire-based universal screening cannot be implemented for any reason. A laboratory test for serum carbohydrate-deficient transferrin (CDT) can be used to detect very heavy drinking. In addition to serving as a cost-effective alternative to questionnaire-based screening, a CDT test may, when administered in addition to a questionnaire, detect heavy drinking in some instances where the results of the questionnaire alone are negative.

Biological alcohol markers are used to identify excessive alcohol consumption and include CDT, gamma-glutamyl transferase, mean corpuscular volume, aspartate aminotransferase, and alanine aminotransferase. Among the different biomarkers of chronic alcohol use, CDT is recognized worldwide as the most reliable indicator of alcohol abuse.1) CDT represents a group of minor glycoforms of human transferrin with a lower degree of glycosylation, comprising asialo-, monosialo-, and disialo-transferrin.2) Abnormal CDT level indicates the accumulated effect of alcohol consumption; can be detected for at least one week after regular alcohol consumption of 50–80 g/d, and normalizes slowly during abstinence (half-life, approximately 15 days).3) Furthermore, as the CDT levels are less affected by the presence of liver diseases,4) it has a distinct advantage over other viable alcohol abuse biomarkers and can help differentiate between alcohol-induced hepatopathy and liver disorders of other origins.

However, the CDT cut-off value used in young men may not be applicable to the elderly due to factors affected by aging. Aging is associated with changes in body composition, muscle strength, a decrease in body weight, decrease in alcohol dehydrogenase activity, and an increase in body fat, all of which may eventually affect the process of alcohol metabolism.56)

A previous epidemiological study reported that healthy men aged ≤65 years who consume more than four standard drinks/d or more than 14 drinks/wk are at an increased risk of developing alcohol-related complications.7) Another study defined at-risk drinking for healthy women and men aged ≥65 as more than three standard drinks/d or more than seven drinks/wk8); a stricter criterion than that for the general population.

Despite the different age-based moderate drinking criteria, no previous studies have reported a validated CDT cut-off value for elderly men. Therefore, this study was conducted to re-evaluate CDT cut-off value for Korean men aged ≥65 years to determine at-risk drinking based on heavy, and binge drinking definitions.

METHODS

1. Subjects

Elderly Korean men (≥65 years, n=120) who visited the department of family medicine at the Chungnam National University Hospital for a health check-up between January 2010 and August 2013 were included in this study. Further, we selected only those men who requested a health examination package that included a CDT test. Men with a recent medication history during the recent one month and those with a body mass index (BMI) of >25 kg/m2 were excluded. Also, men in whom ultrasonography imaging revealed abnormalities such as liver cirrhosis or other hepatobiliary tract diseases, were excluded. Further, we only selected participants who tested negative for hepatitis B and C.

2. Data Collection

Data on alcohol consumption frequency and pattern, and on the patients' CDT levels were obtained from medical records. The CDT level was measured through immunonephelometry using N Latex CDT Kit (Siemens, Marburg, Germany), and was expressed as %CDT.

Age, weight, BMI, smoking status, and exercise frequency were assessed. Based on smoking history, patients were classified as either smokers, ex-smokers, or non-smokers. Patients' exercise frequency was classified as no exercise, irregular exercise, or regular exercise, which was defined as 30 minutes of moderate activity five times/wk, or at least 20 minutes of vigorous activity three times/wk.9) At-risk drinking included heavy and binge drinking. We utilized the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA)8) guideline to define heavy drinking as more than seven drinks/wk, and binge drinking as more than three standard drinks/d for healthy men aged ≥65 years. A standard drink was defined as 14 g of alcohol, as set by the NIAAA guidelines.8)

3. Statistical Analysis

The cut-off %CDT values for at-risk, heavy, and binge drinking were estimated based on the highest Youden index for areas under independent receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) curves. Youden index was calculated using the following formula: sensitivity+specificity-1. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value for all estimated cut-off values were calculated. The Window SPSS software ver. 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all statistical analyses, and a value of P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

1. General Characteristics of the Study Participants

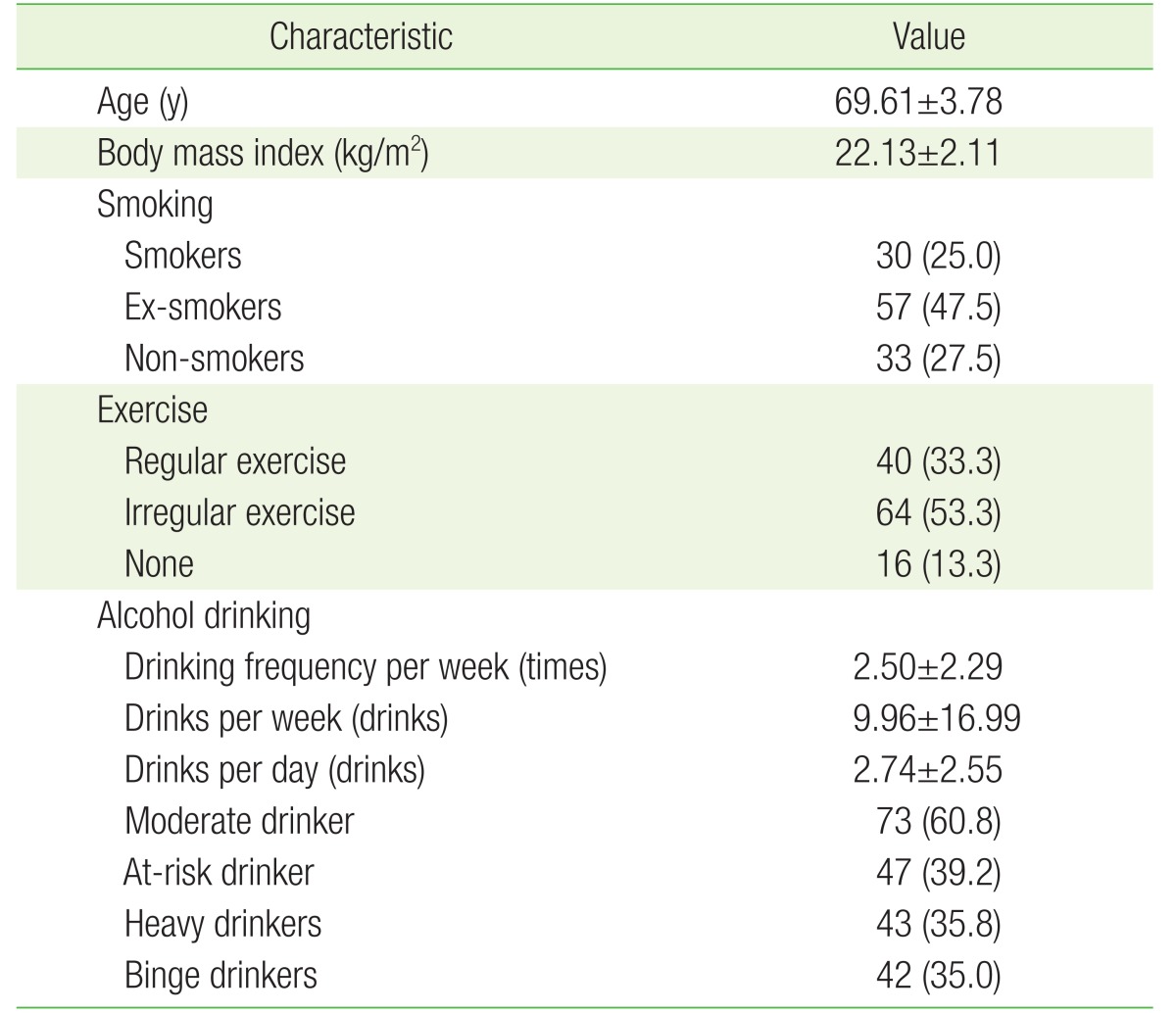

The mean age of the study population was 69.61±3.78 years, and the mean BMI was 22.13±2.11 kg/m2. Based on smoking history, 30 subjects (25.0%) were current smokers, 57 (47.5%) were ex-smokers, and 33 (27.5%) were non-smokers. Based on exercise frequency, 40 subjects (33.3%) exercised regularly, 64 (53.3%) exercised irregularly, and 16 subjects (13.3%) did not exercise. The average drinking frequency (mean±standard deviation) was 2.50±2.29 times/wk, the average alcohol consumption was 2.74±2.55 drinks/drinking day, and the weekly drinking average was 9.96±16.99 drinks/wk. Seventy-three (60.8%) of the 120 participants were moderate drinkers, and 47 (39.2%) were at-risk drinkers. Forty-three subjects (35.8%) were heavy drinkers, and 42 (35.0%) were binge drinkers (Table 1).

2. %CDT Cut-Off Values, Sensitivity, Specificity, Positive, and Negative Predictive Values, and the AUROC for At-Risk, Heavy, and Binge Drinking

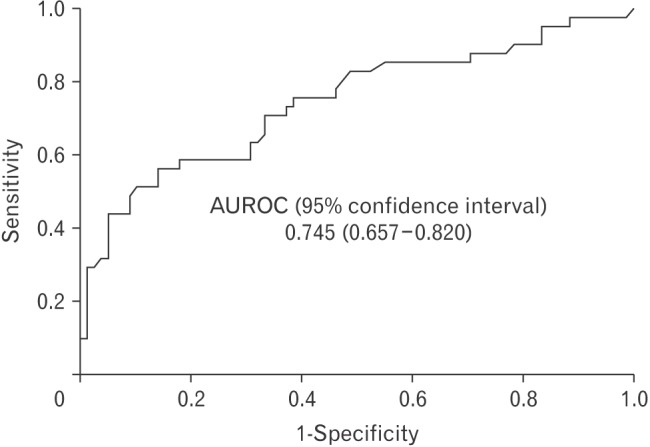

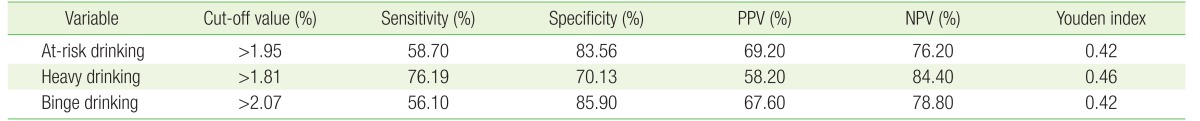

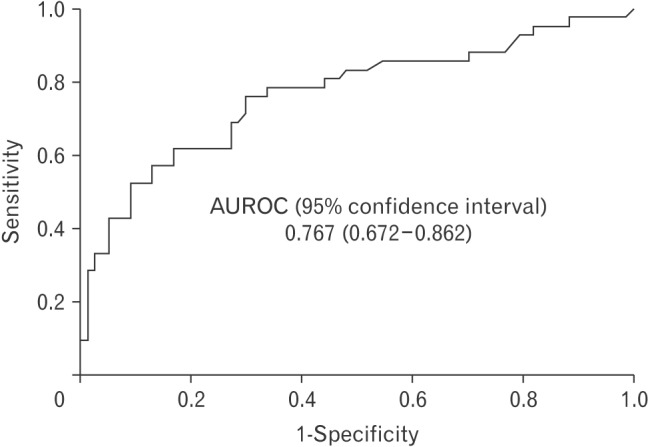

The optimal %CDT cut-off values were estimated using receiver operating characteristics curves and was 1.95% for at-risk drinking in men aged ≥65 years, with the highest Youden index of 0.42. The optimal %CDT cut-off values, along with their highest Youden index, for heavy drinking and binge drinking were 1.81% and 0.46, and 2.07% and 0.42, respectively. The sensitivity, specificity, positive, and negative predictive values for the optimal at-risk drinking %CDT cut-off were: 58.7%, 83.6%, 69.2%, and 76.2% (Table 2). The AUROC were >0.7 for all three evaluated cut-offs (Figures 1,2,3).

Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV for %CDT in screening at-risk, heavy, and binge drinking among elderly Korean men aged 65 years and above

Receiver operating characteristic curve for %CDT in screening at-risk drinking among elderly Korean men (≥65 years). AUROC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; CDT, carbohydrate-deficient transferrin.

Receiver operating characteristic curve for %CDT in screening heavy drinking among elderly Korean men (≥65 years). AUROC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; CDT, carbohydrate-deficient transferrin.

DISCUSSION

Despite the different age-dependent the criteria to define standard drinking, no previous studies have evaluated and validated the optimal %CDT cut-off value in elderly men. We conducted this study to reevaluate the %CDT cut-off value in ≥65-year-old Korean men for at-risk drinking based on the heavy drinking and binge drinking definitions of NIAAA.

In a previously published study, the cut-off value recommended an upper limit of %CDT of 2.47%, while we readjusted the value to 1.95% as the optimal %CDT cut-off value. However, in that study, an elevated alcohol consumption level in the study population was excluded by only selecting nonalcoholic healthy men.10)

Both age and alcohol consumption patterns are known to affect the levels of alcohol biomarkers,11) and in this respect, previous studies support our findings. Studies by Yersin et al.12) and Huseby et al.13) reported that the %CDT values decreased with age and that the highest %CDT levels were observed in younger patients. While alcohol consumption in moderate quantity confers general health benefits, the elderly subjects may experience negative health consequences from even moderate alcohol consumption (e.g., 1–2 drinks on most days).14) Furthermore, in considering other age-related factors common to the elderly, such as a higher use of medications and decreased physical activity, lowering the %CDT cut-off value may be of importance and may help physicians screen and counsel this specific group of patients.

In our study, the sensitivity and specificity of %CDT cut-off values were 58.70% and 83.56% for at-risk drinking, 76.19% and 70.13% for heavy drinking, and 56.10% and 85.90% for binge drinking, respectively. Nystrom et al.15) recommended serum %CDT as the early detection method to identify heavy drinking in young students. However, the %CDT cut-off, in that case, exhibited a low sensitivity of 21.7%. In another study, Agelink et al.16) reported that %CDT was more sensitive in patients aged >40 years than in younger patients. The researchers classified their study population into two age-based subgroups: group I, ≤40 years; and group II, >40 years. In doing so, the sensitivity of the evaluated %CDT cut-off was 81% in group II subjects aged >40 years even after 5 days of abstinence, whereas, in group I, the sensitivity was only 35%.

The diagnostic accuracy of a test may be interpreted using the AUROC analysis; an area >0.9 demonstrates a higher diagnostic accuracy, while 0.7–0.9 indicates a moderate accuracy, and 0.5–0.7 indicates a low diagnostic accuracy.17) In our study, all three drinking patterns exhibited an AUROC of >0.7, and showing statistical significance.

However, the following limitations should be considered when interpreting our findings. As the drinking frequency and quantity were self-reported, some patients may have under-reported their drinking frequency and may thus have been misclassified. Nonetheless, evidence suggests that self-reported alcohol consumption frequency tends to be reliable, and therefore, valid.18) Secondly, as this study was retrospective in design and included a small study population of selectively chosen men, the results may not be adequately generalizable.

In summary, our study suggests that when identifying at-risk drinking in ≥65-year-old elderly men, the %CDT cut-off value should be adjusted to a lower value of 1.95%. Patient histories and the administration of universal screening questionnaires are essential in detecting unhealthy alcohol use. However, when the physician time is limited and screening methods are not adaptable, biological alcohol markers such as CDT may aid in identifying elderly patients at an increased risk of increased alcohol consumption and can prevent the underestimation of heavy drinking in the elderly.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.