Written Asthma Action Plan Improves Asthma Control and the Quality of Life among Pediatric Asthma Patients in Malaysia: A Randomized Control Trial

Article information

Abstract

Background

A written asthma action plan (WAAP) is one of the treatment strategies to achieve good asthma control in children.

Methods

This randomized controlled trial was conducted to observe the effect of WAAP on asthma control and quality of life using the Asthma Control Questionnaire and Pediatric Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (PAQLQ) at baseline and after 3 months. A repeated measure analysis of variance was used to analyze the mean score difference between the two groups.

Results

There was no significant difference in mean score for asthma control at baseline between groups (F[degree of freedom (df)]=1.17 [1, 119], P=0.282). However, at 3 months, a significant difference in mean scores between groups was observed (F[df]=7.32 [1, 119], P=0.008). The mean±standard deviation (SD) scores in the intervention and control groups were 0.96±0.53 and 1.21±0.49, respectively. For the analysis of the PAQLQ, no significant difference was observed in the mean score for the quality of life baseline in both groups. There were significant mean score changes for the quality of life (F[df]=10.9 [1, 119], P=0.001) at 3 months follow-up, where those in the intervention group scored a mean±SD score of 6.19±0.45, and those in the control group scored 5.94±0.38. A time-group interaction analysis using repeated-measures analysis of variance showed significant differences in mean score changes (F[df]=5.03 [1, 116], P=0.027) and (F[df]=11.55 [1, 116], P=0.001) where a lower mean score was observed in the intervention group, indicating better asthma control and quality of life, respectively. A significant (P<0.001) negative Pearson correlation between asthma control and quality of life (-0.65) indicated a moderate correlation.

Conclusion

WAAP, along with standard asthma treatment, improves asthma care.

INTRODUCTION

Several international guidelines advocate the use of asthma education to improve asthma control and increase the quality of life among affected children. Good doctor-patient communication and education on family empowerment were found to be effective in achieving asthma control [1]. Importantly, asthma education can help reduce the gap in managing asthma in poor countries due to the inaccessibility of asthma medications [2]. It has been observed that a good understanding of the illness and the correct use of medications resulted in a significant reduction in hospital admissions and emergency department visits. Another study in Delhi, India, had shown a significant result, stating that standard treatment combined with asthma education will improve asthmatic control [3].

An asthma action plan is a method of asthma education. It is an individualized written instruction to a patient on how to monitor asthma control, adherence to medications, and avoidance of allergens. It also involved the recognition of acute asthma attacks, so that prompt action could be taken when they occurred. A written asthma action plan (WAAP) is recommended for patients with partly controlled asthma, patients with uncontrolled asthma, and patients with a history of severe asthma [4]. The physician can also discuss with their patients how to adjust medications in certain situations and when to seek early medical attention. A study conducted in Singapore showed that parents were more confident and had a better understanding of the illness when WAAP was used [5].

However, there are other conflicting evidences on the use of an asthma action plan in improving the quality of life and asthma control among sufferers. A study in an urban area in Malaysia did not find significant results on the use of an asthma action plan with asthma control and the quality of life [6]. Additionally, Kelso [7] found that those with WAAP had an increased rate of hospitalization among pediatric asthmatic patients.

This study was performed because there are several inconsistencies in the results of previous studies. Furthermore, several asthmatic children in Malaysia are still having poor asthma control, and yet, an asthma action plan is not widely practiced as an integral part of asthma management. The purpose of this study was to assess and demonstrate the efficacy of WAAP in improving asthma control in younger children with partly controlled and uncontrolled bronchial asthma.

METHODS

This was a single-blind, parallel, hospital-based, randomized control trial conducted among 120 asthmatic children aged 6 to 12 years old in the Pediatric Clinic, Hospital Kuala Terengganu, Malaysia. This is a multidisciplinary specialty clinic catering to various pediatric conditions, including asthma. The patients were referred from Kuala Terengganu and surrounding districts.

Participants with partly controlled and uncontrolled asthma were selected with their consent. Subsequently, they were allocated into the intervention or control groups by computer-based simple randomization. An assessment of asthma control and quality of life was done at the baseline visit. The participants were all interviewed alone by the researcher using the Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ) and Pediatric Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (PAQLQ). After completing the questionnaires, they had their peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) done 3 times, and the highest reading was taken.

Asthma education was provided and individualized WAAP were explained to the patients and caretakers in the intervention group during the first visit. The WAAP was brought home as guidance and was to be used when patients had an asthmatic exacerbation. In contrast, the patients and caretakers in the control group only received asthma education and a verbal asthma action plan during the first visit. A 3-month follow-up appointment date was given to all participants, during which the post-intervention assessment of ACQ and PAQLQ was conducted.

The study kits, which contained research tools, were put in sealed, non-transparent envelopes and were color coded to differentiate between the interventional (receiving WAAP) and control groups (not receiving WAAP). Those in the interventional group received ACQ, PAQLQ, WAAP, and asthma education pamphlets, while those in the control group only received ACQ, PAQLQ, and asthma education pamphlets. The participants came into the interviewer’s room with their call numbers, and using the computer-generated sequence before, they received the study kit as per their assigned group (Figure 1).

Study flowchart. ACQ, Asthma Control Questionnaire; PAQLQ, Pediatric Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire.

1. Research Tools

There were a few research tools that were used in the study. The first tool was the asthma education flip chart. It was a laminated, colorful flip chart used to deliver standard asthma education to both caretakers and patients. It was obtained from the Health Education Department, Ministry of Health Malaysia. The content of the pamphlet included the nature of the disease, exacerbating factors, different uses of medications, and inhaler techniques. The correct inhaler technique was discussed and emphasized during the visit. Notably, several caregivers and patients were comfortable with using a spacer for better delivery of medications. The researcher explained and demonstrated the correct use of a metered-dose inhaler (MDI) and spacer using a sample MDI and spacer.

The second research tool was a WAAP. An asthma action plan is an individualized written instruction to the patients and caretakers on how to monitor the symptoms of asthma, adherence to medications, and how to recognize exacerbations; thus, prompt action can be taken at home. They were taught how to recognize the severity of an exacerbation and, thus, adjust the medications accordingly. They were also educated on when to seek early medical attention.

The third tool was ACQ. This study had written permission to use ACQ, which was developed by Dr. Elizabeth Juniper. It is a worldwide validated questionnaire that is used with subjects aged 7–17 years. ACQ has strong evaluative and discriminative properties and can be used with confidence to measure asthma control [8]. It includes seven questions regarding the daytime and nighttime symptoms, limitation of daily activity, wheezing, bronchodilator use, and measurement of forced expiratory volume at 1 second or PEFR. Patients were asked to recall their asthma symptoms over the previous week and respond to questions on a 7-point scale. For analysis, a higher score indicated worse asthma control. A score of ≤0.75 was regarded as controlled asthma, and ≥1.5 was regarded as uncontrolled asthma. An in-between value was regarded as partly controlled asthma.

ACQ had been translated into Malay, widely used across the regions, and has been translated by the Modified Asthma Predictive Index (MAPI) Research Institute, Lyon, France [9]. Interviewer-administered ACQ took place without the caretakers in the room to avoid bias. Generally, all the patients recruited were able to describe their symptoms well. However, when the research was conducted, a recall bias was anticipated, and to minimize this, the PEFR value was compared with the previous PEFR for medication adjustment.

The fourth tool was PAQLQ. It was also developed by Dr. Elizabeth Juniper and showed good validity as an evaluative instrument in patients aged 7–17 years [10]. Studies showed that children as young as 7 years old had no difficulties understanding the questions and were able to provide accurate responses with a Cronbach’s α of 0.87 [11,12]. A study that used the Malay-translated PAQLQ also did not report any difficulties in using the questionnaires when given to patients aged 6–17 years [6].

The PAQLQ consisted of 23 questions covering three major domains in assessing the quality of life: activity limitations, symptoms, and emotional function. It is a Likert-scaled questionnaire, scoring 1 to 7, where 1 indicates severe impairment and 7 indicates no impairment. Thus, in PAQLQ scoring and analysis, a higher score reflects a better quality of life and is analyzed using the mean score. The validity was tested in several countries. It was culturally adapted and translated into multiple languages again by the MAPI Research Institute, Lyon, France [13].

2. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to describe univariable data. The objectives of the study were to determine the effectiveness of WAAP by comparing the asthma control and quality of life of both the control and interventional groups at baseline and follow-up using a repeated-measures ANOVA (RM ANOVA) as statistical analysis.

3. Ethical Consideration

This study (research identification no., NMRR-15-193526169; ID no., 26169) was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of Medical Sciences, Health Campus, Universiti Sains Malaysia with study protocol code USM/JEPeM/15030085. Since the study site was a government hospital, the study was also approved by the National Medical Research Committee and Ministry of Health Malaysia Ethical Committee. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

RESULTS

A total of 120 of the 129 children completed the study, with a response rate of 93%. Notably, 61 children received WAAP (intervention group), whereas 59 children did not receive WAAP (control group). Nine children were withdrawn because they did not attend the follow-up visit.

1. Socio-Demographic Data of the Studied Subjects

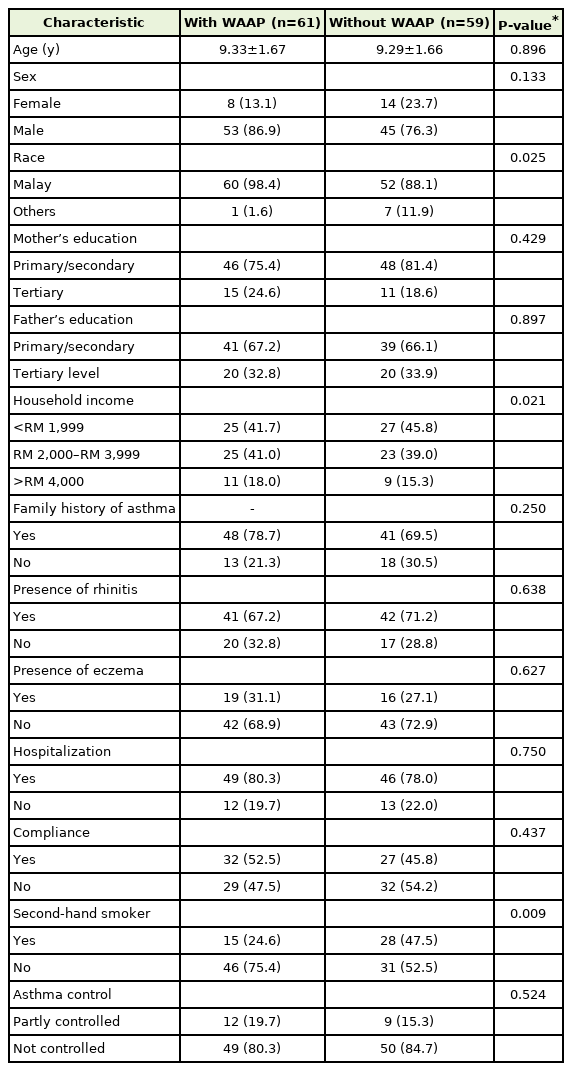

Table 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the subjects. There were no significant differences in the characteristics of the respondents between the intervention and control groups at baseline except for race, household income, and exposure to being a secondhand smoker.

2. The Effectiveness of the Written Asthma Action Plan on Asthma Control Using Asthma Control Questionnaires

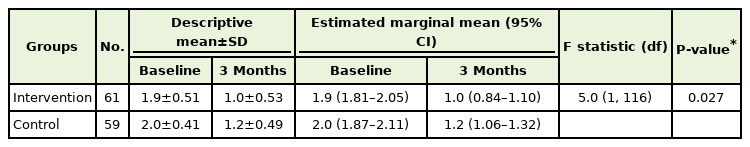

Table 2 shows an RM ANOVA analysis comparing the mean scores of both groups based on the time-group interaction while adjusting for compliance and second-hand smokers. Race and household income were not adjusted because asthma was not found to be associated with ethnicity, and local studies in Malaysia countries show that household income has no effect on asthma control [14,15]. Furthermore, the numbers of non-Malays were small, and children in Malaysia country are fully funded by medical care when attending government medical centers. Therefore, those factors were not included in the main RM ANOVA analysis.

Comparison of the Asthma Control Questionnaire score between the intervention and control group based on time-group interaction (N=120)

1) Descriptive analysis

In the intervention group, the mean score±SD was 1.9±0.51 at baseline and improved to 1.0±0.53 at 3 months. In the control group, the mean score was 2.00±0.41 and has also improved to 1.2±0.49.

2) Univariate analysis

An ANOVA analysis showed no significant difference in the mean score of both groups at baseline (F[degree of freedom (df)]=1.17 [1,119], P=0.282); however, a significant difference was seen at the 3-month follow-up (F[df]=7.32 [1, 119], P=0.008). Those who had received WAAP had a lower crude mean compared to those who did not receive WAAP.

3) Time-group interaction

The time-group interaction using RM ANOVA after adjusting for compliance and second-hand smoke showed a significant difference in mean score changes (F[df]=5.03 [1, 116], P=0.027) between the intervention and control groups. At the 3-month follow-up, there was a lower mean±SD score of 1.0±0.53 in the intervention group, indicating better asthma control in this group compared to the control group with a mean±SD score of 1.2±0.49.

3. The Effectiveness of a Written Asthma Action Plan on the Quality of Life Using the Pediatric Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire

Table 3 showed the total and subdomain means of a score of PAQLQ between the intervention and control groups.

1)Descriptive analysis

There was a significant difference in the total mean total score (F[df ]=10.9 [1, 119], P=0.001) and subdomain mean score at the 3-month follow-up, where a higher mean±SD score was seen in the intervention group: 6.2±0.45 compared to the control group; 5.9±0.38 indicating a better overall quality of life in those with WAAP at the 3-month follow-up.

2) Time-group interaction

The RM ANOVA analysis showed significant differences in the mean PAQLQ change scores between both groups (F[df]=11.55 [1, 116], P=0.001) after adjusting for compliance and second-hand smokers, based on Table 4. During the follow-up at 3 months, the intervention group scored higher than that of the control group, indicating a better quality of life among pediatric asthmatic patients in the former group.

Comparison of subdomain of PAQLQ score between the intervention (N=61) and control groups (N=59) based on time-group interaction (N=120)

Further analysis of the subdomains of the PAQLQ revealed that there were significant mean PAQLQ score changes in the symptoms and emotional function domains at 3 months but not in the activity limitation domain (F[df]=204 [1, 116], P=0.155). Although those with WAAP scored better than those without WAAP, there was no significant difference in the activity limitation domain mean score.

There was a significant (P<0.001) negative Pearson correlation between asthma control and quality of life (-0.65) between asthma control and quality of life among pediatric asthma patients, indicating a moderate correlation. This means that better asthma control will increase the quality of life of the subjects using a WAAP.

DISCUSSION

This study showed that the majority of the respondents were Malays, which constituted about 93% of the total respondents. This is because the study was conducted in Kuala Terengganu and was based on the 2010 National Census. Approximately 94.7% of the total population of Terengganu is Malays, which is higher than the national numbers, constituting only 63.1% [16].

In this study population, more children came from a lower household income group placed in the control group compared to the interventional group. This may be because the selection of the respondents into both the interventional and control groups was done by simple randomization; thus, the distribution into groups was by chance. Studies in Western countries suggest that parents with lower socioeconomic status are predisposed to the risk of severe asthma due to limited health insurance coverage in this group [17,18]. This situation might not be applicable in this study as these children were receiving government-funded medical care. Thus, the issue of inaccessibility to medical treatment due to lack of insurance coverage might not be a significant contributing factor among children in this study.

In this study, 43 subjects (36%) were exposed to tobacco smoke at home. Being a second-hand smoker reduced the efficacy of inhaled corticosteroids and affected the child’s school performance as the number of sick days increased [19]. However, in this study, being a secondhand smoker was not strictly defined. From the data presented, the distribution of second-hand smokers was not equally distributed between groups. It can be observed that a larger number of pediatric asthmatic patients who were second-hand smokers were placed in the control group. Since patients were randomly assigned to either the interventional or control group, this effect was beyond control and can be buffered if we can recruit more respondents to this study. However, during data analysis, second-hand smoker exposure was controlled during the assessment of asthma control and quality of life.

1. The Effectiveness of a Written Asthma Action Plan on the Asthma Control

In the current study, both groups showed better asthma outcomes at the 3-month follow-up based on the ACQ score. As shown in Table 2, those in the intervention group had a lower mean ACQ score, which was 1.0, compared to the control group, which was 1.2. Although both groups only achieved a partly controlled asthma status after 3 months, those in the intervention group had a better score by using WAAP in asthma management. This finding was similar to a study conducted in India, where participants also achieved a controlled asthma status after education intervention over a 3-month study period. Their results also showed a statistically significant difference in the mean asthma control score in a few domains of ACQ [3].

Based on the time and group interaction analysis, a significant difference in the mean ACQ was seen at the 3-month follow-up with P=0.00. This reflected the fact that WAAP is an important and useful method to improve asthma control among pediatric patients. A subanalysis of the study also found that those in the intervention group had few unscheduled doctor visits due to the exacerbation of asthma (F[df]=11.29 [1, 119], P=0.001). This finding was in contrast to a local study at University Malaya Medical Centre in 2010 [6]. They found that WAAP did not reduce unscheduled doctor visits even though asthma control was better. The reason for the difference is not clear; however, it may have something to do with a different study population. The study comparison emphasized the WAAP alone; however, this study also included standard asthma education as a part of the routine management of childhood asthma. This finding suggested that WAAP should be given as a part of asthma education, as suggested by other studies, as it would not be beneficial if used alone [7].

However, by providing an asthma action plan in the health center setting, caretakers were more confident in adjusting the medications where needed without putting the child at risk by delaying the decision to seek acute care at health facilities [5,20]. Thus, caretakers able to assess the severity of the asthmatic symptoms will seek treatment appropriately. Therefore, we can advocate the use of WAAP in the clinical setting for managing pediatric asthma patients.

As suggested by Global Initiative for Asthma guidelines, the WAAP included instructions to increase the controller and reliever MDI doses and add on oral corticosteroids [21]. However, in this study, the caretakers and patients were only advised to increase the doses of the reliever MDI. This was because several patients were on the maximum dose of inhaled corticosteroids and there was limited evidence to suggest that doubling the inhaled corticosteroid during exacerbation will reduce the need for oral corticosteroids [22]. Besides, the practice of prescribing oral corticosteroids as per need when developing exacerbation of asthma at home is not practiced widely in Malaysia.

Nevertheless, the long-term effect of WAAP on maintaining good asthma control was not studied in this study due to the time limitations of the study period. A study by Kotwani and Chhabra [3] assessed the effect of WAAP for 12 weeks. They studied whether the asthma action plan had a legacy effect over time when the respondents were followed up after 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks of post asthma education [3]. In this study, they found out that the effect of the educational intervention persisted until the 12-week follow-up in terms of asthma control indicating that standard asthma education gave a positive effect on asthma control over a period of time. There was another study done over 9 months that showed a positive effect on WAAP and asthma control even though it was not statistically significant [6].

Studies on the effectiveness of asthma education on asthma control were robust with different study outcomes. However, a systematic review proposed that for asthma education, including an asthma action plan, to be effectively delivered as a part of an asthma control program, it should be individualized, continuous, progressive, sequential, and dynamic [23]. The asthma action plan is an option to be delivered to caretakers during follow-ups as a reminder, as it is an individualized and dynamic plan on asthma management catering to different severities of symptoms of asthma in a child. It is also a tool with which health care providers, especially attending doctors, can have more focused management of various problems faced by the caretakers or the asthmatic children at home during their regular follow-up visits. The practice has been shown to have a greater impact on health indicators and quality of life.

2. The Effectiveness of Written Asthma Action Plan on Pediatric Asthma Quality of Life

The mean PAQLQ score was 5.3 at baseline for both groups (P=0.94). However, at the 3-month follow-up, there was a significant increment in the PAQLQ score in both groups, with high increments seen in those receiving WAAP at 3 months, which was statistically significant. The mean±SD score for those in the interventional group was 6.2±0.45 as compared to the control group’s 6.0±0.38 (P=0.001). It was an anticipated outcome, as the quality of life perceived by the patients usually reflected their experience and satisfaction with the treatment given to them. Thus, the quality of life is expected to be better if the disease outcome is improved.

A better quality of life, which was assessed, reflected the improvement in daily activities, symptoms, and emotional function. Several studies were able to demonstrate the improvement in the quality of life of pediatric asthmatic patients after asthma education interventions [24]. It is known that the quality of life is related to the improvement of asthma control, and better asthma control is related to knowledge of the disease [25]. Face-to-face asthma education and an asthma action plan were given during the study. When the discussion was made, the caretakers were open to discussing the illness. Face-to-face asthma education was observed to be more effective in improving asthma control and, subsequently, the quality of life as compared to home-based interventions [3,26]. In terms of an individualized asthma action plan, symptoms-based asthma management modification was used rather than a PEFR-based action plan. Thus, the caretakers will take the initial steps even when their children develop exacerbation symptoms. The assessment of symptoms to predict exacerbation is better than PEFRbased prediction for prompt action to be taken by caregivers at home to prevent further deterioration of symptoms at home [27].

The study outcome showed an overall significant improvement in the quality of life among partly controlled and uncontrolled asthmatic patients when a WAAP was provided as an adjunct to asthma education. However, based on the analysis of the subdomains of the PAQLQ, there was only a statistically significant improvement in the symptoms and emotional function subdomains in the intervention group but not in the activity limitation domain (F[df]=2.04 [1, 116], P=0.155). This was contrary to a study done in a tertiary center in Iran that showed asthma education significantly improved the quality of life among pediatric asthmatic patients in all domains after the 2-week intervention [28]. In the study, they provided intensive asthma education to the caretakers and patients over 4 weeks, and the outcomes were assessed 2 weeks later. In another study, it was found that there was a significant limitation of activity among uncontrolled asthmatic patients as compared to patients with asthma with controlled and partly controlled statuses [25]. This study studied the effect of WAAP along with brief standard asthma education and the outcome measured after 12 weeks. Thus, we suggest that more intensive and regular educational intervention is needed to improve the activity limitation among pediatric asthmatic patients.

There were multiple factors causing inactivity among pediatric asthmatic patients. It can be due to the policy of schools to limit children with asthma on physical activity at school, misinterpretation of the symptoms while exercising, and acceptance of the caretakers regarding their children’s illness and limitations [29]. However, we should encourage asthmatic children to go out playing for their overall health and socio-emotional development.

After 3 months of study, the overall control status of the participants’ asthma was partly controlled. The finding may explain the non-significant improvement in daily activities among patients, as asthmatic children with partly controlled asthma were more affected compared to patients with controlled asthmatic status in terms of physical activity limitations [29]. When exercising, the children need to know the symptoms of exacerbation; thus, prompt action can be taken during the exacerbation to plan the type and intensity of the exercise in the future.

Other subdomains studied included symptoms and emotional function. The children were questioned about the presence of asthma symptoms, such as coughing, wheezing, nighttime symptoms, and asthmatic attacks, for the past week. The uncontrolled symptoms affected the school performance of asthmatic children since they felt sleepy at school, increased school absenteeism, and increased unscheduled doctor visits [20,30]. Subsequently, they were assessed on the emotional function due to the illness, for example, feeling isolated or different from others, frustration, irritability due to asthma, and anticipation of asthmatic attacks, which made them more careful. The impact on the social function of the child with asthma should be recognized; additionally, this study shows similar findings to other studies showing that the improvement of the quality of life is correlated with control of asthma status [28].

The improvement of the quality of life is important as children are growing, and during this age group, they need to be recognized and function socially; thus, it should be ensured that the emotional health and self-esteem of a child are not affected by the disease. This is important for preparing them to be better and healthier individuals in the future. The use of WAAP can help the caretakers and patients to be in control of their asthma where they are more aware of the illness, empower themselves in the self-management of asthma at home, and subsequently improve the asthma outcomes in terms of asthma control and the quality of life.

3. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study has shown positive outcomes of the use of WAAP in improving asthma control and indirectly improving the quality of life among asthmatic pediatric patients who had partly controlled and uncontrolled asthma among the semi-urban population in the clinical setting. WAAP should be used as an adjunct tool to standard face-to-face asthma education for caretakers and patients.

4. Study Limitations

This study examined the effectiveness of WAAP in improving asthma control and quality of life among pediatric asthmatic patients aged 6 to 12 years old. The asthma control and quality of life were assessed using the ACQ and PAQLQ questionnaires, and the children were interviewed individually. Thus, recall bias may be a limitation of this study.

Compared to another study, this study only analyzed the effectiveness of the WAAP over a 3-month duration. The long-term effect of WAAP was not studied due to time limitations. The study needed to be extended during the patients’ recruitment phase as it was quite difficult to recruit participants that fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Thus, the long-term sustainability effect of WAAP in improving asthma control and quality of life could not be studied.

During the study, several respondents who were not in the WAAP group had smokers in their homes. As discussed previously, smoke negatively impacts asthma control. Thus, the outcome of this study in the control group may be affected by the presence of smokers in the house.

5. Recommendations

This study recommends that an individualized WAAP be given to caregivers and pediatric asthma patients, especially for those with partly controlled and uncontrolled asthmatic status, to improve the disease outcome. However, WAAP did not substitute the role of asthma education as a part of the management of asthma. Future studies should be carried out to observe the long-term effectiveness of WAAP with a proper definition of tobacco smoke exposure to reduce biases in the study.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.