Effect of Curcumin on Dysmenorrhea and Symptoms of Premenstrual Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Article information

Abstract

Background

Dysmenorrhea and premenstrual syndrome (PMS) are common periodic and frequent complications in women of reproductive age that can negatively affect health and quality of life. The present study examined the effects of curcumin on the severity of dysmenorrhea and PMS symptoms.

Methods

A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials was conducted by searching databases such as the Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Scopus, PubMed, and Web of Science from inception to January 2023. Article screening was performed using Endnote ver. X8 (Clarivate). Review Manager (RevMan ver. 5.3; Cochrane) was used for the quality assessment and meta-analysis. A total of 147 studies were screened, of which five were finally selected for quantitative and qualitative analyses. The studies were conducted between 2015 and 2021, and a total of 379 participants with a mean age of 23.33±5.54 years had been recruited in these studies.

Results

The meta-analysis showed that curcumin consumption could significantly reduce the severity of dysmenorrhea (mean difference, -1.25; 95% confidence interval [CI], -1.52 to -0.98; three studies; I2=31%) and the overall score of PMS (standardized mean difference, -1.41; 95% CI, -1.81 to -1.02; two studies; I2=0%).

Conclusion

The reduction in the severity of PMS and dysmenorrhea has been attributed to curcumin’s anti-inflammatory and antidepressant activities. Although the findings suggest that curcumin may be an effective treatment for reducing the severity of PMS and dysmenorrhea, further research with a larger number of participants from various socioeconomic levels and a longer duration of treatment is needed to evaluate the effective dose of curcumin.

INTRODUCTION

Dysmenorrhea and premenstrual syndrome (PMS) are prevalent and recurrent conditions that may compromise the well-being and quality of life of women of reproductive age [1]. There are two types of dysmenorrhea: primary and secondary. Primary dysmenorrhea is characterized by spasmodic cramping pain in the lower abdomen accompanied by nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, and typically lasts between 12 and 72 hours [2]. Primary dysmenorrhea is very common, and more than 50% of teenagers and 30%–50% of menstruating women suffer from various degrees of this discomfort [3]. Secondary dysmenorrhea results from underlying gynecologic disorders such as adenomyosis, uterine fibroid, or endometriosis, as well as other disorders [4]. PMS is characterized by a range of somatic and psychological symptoms that occur during the luteal phase, from ovulation to the onset of menstrual bleeding [5].

The principal underlying cause of menstrual cramps is ischemia, which is due to uterine contractions caused by prostaglandin secretion during menstruation [6]. According to an Indian systematic review, the pooled prevalence of PMS was 43%, and the prevalence of PMS in adolescence was estimated higher than others, and accounted to be 49.6% [7].

Although there is currently no definitive treatment for PMS and dysmenorrhea, different approaches have been adopted to manage symptoms. These include administration of analgesics, anti-inflammatory medicines, and herbal medicine therapy [8]. The first line of treatment for primary dysmenorrhea typically involves non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) [9]. Additionally, antidepressants and oral contraceptives are also used to manage PMS and dysmenorrhea [8,10]. However, NSAIDs are associated with contraindications, side effects, and a failure rate of approximately 20%–25% [11]. As a result, some women opt for complementary and alternative treatments to alleviate menstrual pain. However, the effectiveness and safety of this type of treatment have not been comprehensively investigated [12]. According to a systematic review in Iran, aromatherapy using Iranian herbs such as lavender and rose may significantly reduce symptoms of primary dysmenorrhea and PMS [13].

A few studies have found that curcumin can alleviate symptoms of dysmenorrhea and PMS [14-16]. curcumin is a yellow polyphenol compound that is the main ingredient of turmeric (Curcuma longa L from the Zingiberaceae family) [17]. It is used as a spice in cooking and as an herb in traditional medicine. Evidence shows that curcumin has pleiotropic effects and acts as an anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antioxidant, and antibacterial agent [18,19]. In addition, curcumin can reduce prostaglandin production [20].

Khayat et al. [15] found that curcumin can alleviate symptoms experienced before menstruation without any adverse effects. Furthermore, curcumin in women with PMS may also regulate neurotransmitters and biomolecules, exert antioxidant and analgesic effects, and reduce oxidative stress [21]. Therefore, the present study aimed to systematically investigate the effects of curcumin on the severity of dysmenorrhea and PMS symptoms.

METHODS

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in compliance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) checklist [22].

1. Search Strategies

Databases, including Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Scopus, PubMed, and Web of Science, were searched from inception to January 2023. The search terms used in this review were: Curcuma OR Curcumin OR Turmeric OR Curcuma zedoaria OR Zedoary zedoaria OR Curcuma longa AND Dysmenorrhea OR Menstrual Pain OR Painful Menstruation OR Menstruation OR Premenstrual Syndrome OR Premenstrual Tension OR Premenstrual Tensions AND Girl? OR Woman OR women.

2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) written in English with accessible full texts were included in the review. We excluded quasi-experimental papers, review articles, studies written in languages other than English, books, articles with descriptive, qualitative, and cross-sectional designs, congress presentations, case reports, and study protocols.

3. Types of Participants

Participants included reproductive-aged women (aged 15–49 years) with primary dysmenorrhea or PMS who had no pelvic pathology based on pelvic examination, ultrasound, or laparoscopy and self-reported primary dysmenorrhea or PMS.

4. Types of Interventions and Comparisons

The RCTs included in this review involved oral administration of curcumin (in the form of capsules, pills, or powders) for the management of dysmenorrhea or PMS. No restriction was set on curcumin dosage, form, or length of treatment. Only RCTs that used drug therapies or placebo as controls were included in this review. All included studies used sugar or carbohydrate as a placebo, which is not considered a treatment for dysmenorrhea or PMS. RCTs using waiting lists, including those with no therapy or relying on complementary or alternative medicine, were excluded.

5. Types of Outcome Measures

Primary outcomes were measured as follows: (1) The severity of dysmenorrhea was measured using a Visual Analog Scale (VAS). (2) PMS severity was measured using a questionnaire. Secondary outcomes were measured as follows: (1) behavioral symptoms of PMS, (2) mood symptoms of PMS, and (3) physical symptoms of PMS were assessed using a questionnaire based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, Self-Rating Scale.

6. Selection of Studies and Data Extraction

The fifth author (M.Z.) conducted the search. The two authors (F.S. and S.F.S.) independently screened the titles and abstracts of all retrieved articles according to the inclusion criteria. The full texts of the relevant studies were thoroughly examined by the same two authors, who independently extracted the data from the included studies. Conflicts were resolved by discussion or assistance from a fourth research team member (Z.M.). All screenings were performed using Endnote ver. X8 (Clarivate, Philadelphia, PA, USA). To extract the data, a table was prepared, including information about the study authors, study location, study design, sample size, participants’ age, questionnaire, intervention, placebo, and outcomes.

7. Assessment of Risk of Bias in the Included Studies

The two authors (F.S. and S.F.S.) independently assessed the risk of bias in the included studies based on the criteria of Cochrane guidelines for assessing the quality randomized clinical trials: (1) allocation concealment (selection bias), (2) random sequence generation (selection bias), (3) blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), (4) blinding of the participants and the personnel (performance bias), (5) incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), (6) selective reporting (reporting bias), and (7) other risks of bias (e.g., calculation of sample size, power of study, receiving consent from participants, and ethical approval) [23].

8. Statistical Analysis

The Review Manager (RevMan ver. 5.3; Cochrane, London, UK) was used to conduct the meta-analysis. The significance level was set at P<0.05. Mean differences (MD) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used to compare variables between the groups. If outcomes were measured using different scales, the standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI were used. The Z-test was used to determine the significance. The heterogeneity of the included studies was evaluated using I2. Forest plots were used to determine the effect sizes and 95% CI. For all the pooled studies, fixed effects were used by default. Based on the initial heterogeneity assessment, we used the random-effects model for I2>35%. Sensitivity analyses were performed by removing individual studies to evaluate the role of moderating papers.

9. Ethics Approval

The Ethics Committee of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences approved the present study (reference no., IR.KUMS.REC.1402.277).

RESULTS

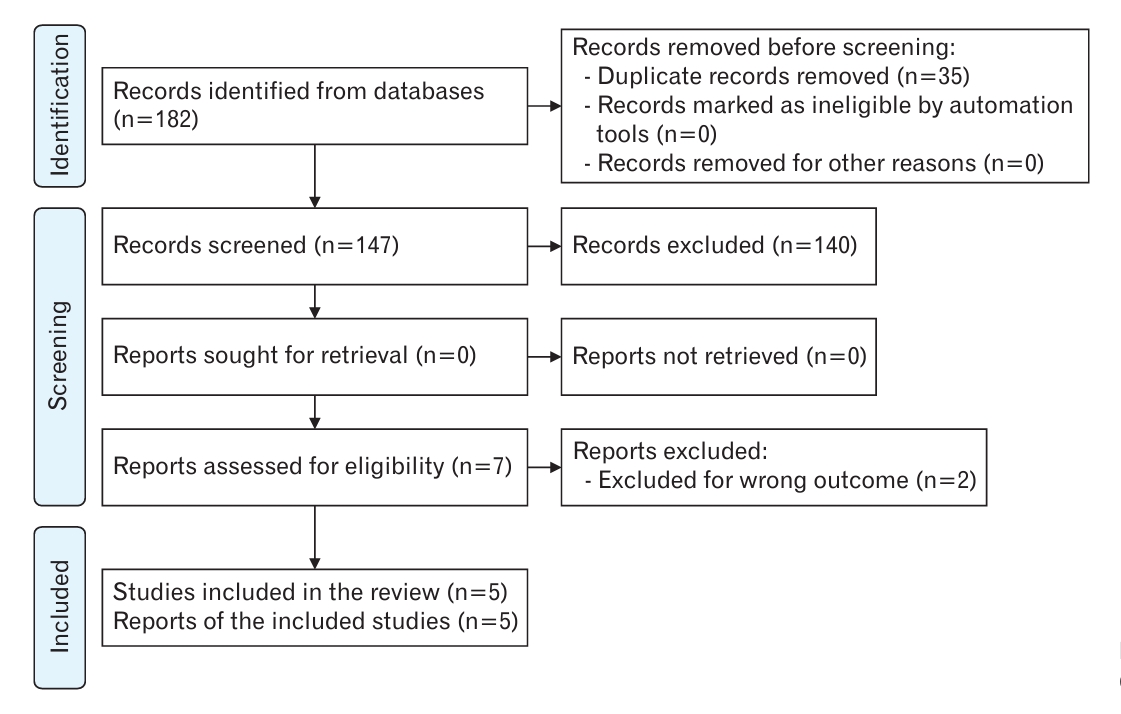

We initially identified 182 published articles after the database search. One hundred forty-seven articles were screened by removing duplicates (n=35); of the remaining articles, seven full-text studies were evaluated in terms of eligibility. Finally, five papers were subjected to quantitative and qualitative analyses [15,24-27]. Figure 1 shows the study flow diagram of the search and selection process of the articles. Two papers were excluded due to wrong outcomes [12,28].

1. Characteristics of the Study

The characteristics of all five randomized, double-, or triple-blind placebo-controlled trials are shown in Table 1. The publication dates of the articles were 2015–2021. A total of 379 participants were recruited in these studies, of which 188 received intervention and 191 received placebo. The sample size of each study was 61–118 women. All included studies were conducted in Iran. The VAS score was used to measure the severity of dysmenorrhea, and a questionnaire designed by the American Psychiatric Association (2000) was used to estimate the severity of PMS. The mean age of the participants was 23.33±5.54 years. All included studies used oral curcumin in various forms (pill, capsule, or powdered) at different dosages, mostly 500 mg once to twice a day [24-26], and in two studies, 100 mg every 12 hours [15,27], for managing dysmenorrhea or PMS.

Two reviewers (S.F.S. and F.S.) assessed the quality of the studies based on the Cochrane Risk-of-Bias tool using the RevMan software (Cochrane). Consultation with a fourth author (Z.M.) was sought if there was any disagreement. Figure 2 illustrates the authors’ judgments regarding the risk of bias in the analyzed studies. As shown in this figure, all studies were in the low-risk area in terms of performance, attrition, and reporting biases. All studies adequately described the randomization technique. However, only one article had mentioned the allocation concealment method. Over 75% of the included papers were in the low-risk area of detection bias.

2. The Severity of Dysmenorrhea

The severity of dysmenorrhea in the curcumin and control groups was assessed in three studies [24-26]. The results showed a significant decrease in dysmenorrhea severity in the curcumin group compared to the control group (MD, -1.25; 95% CI, -1.52 to -0.98; three studies) with low heterogeneity (I2=31%) (Figure 3).

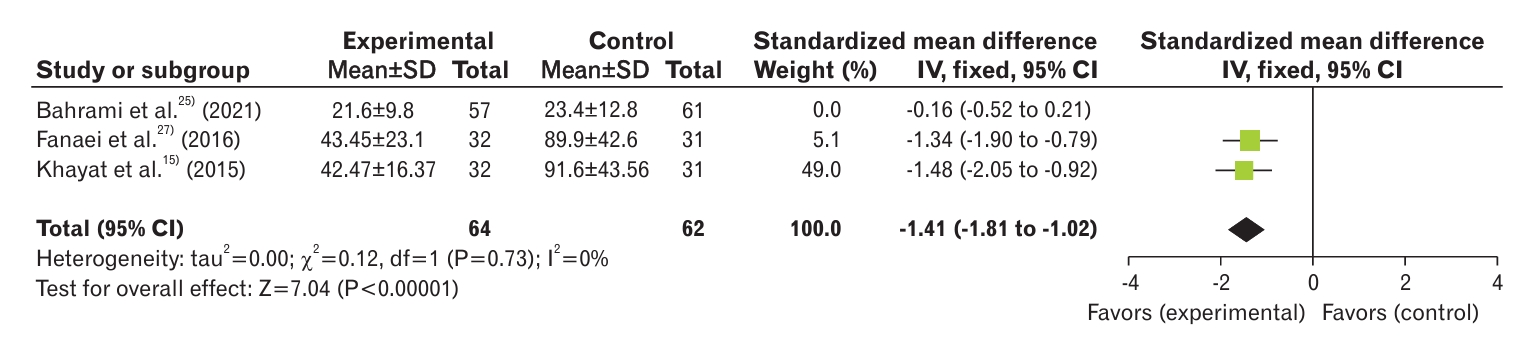

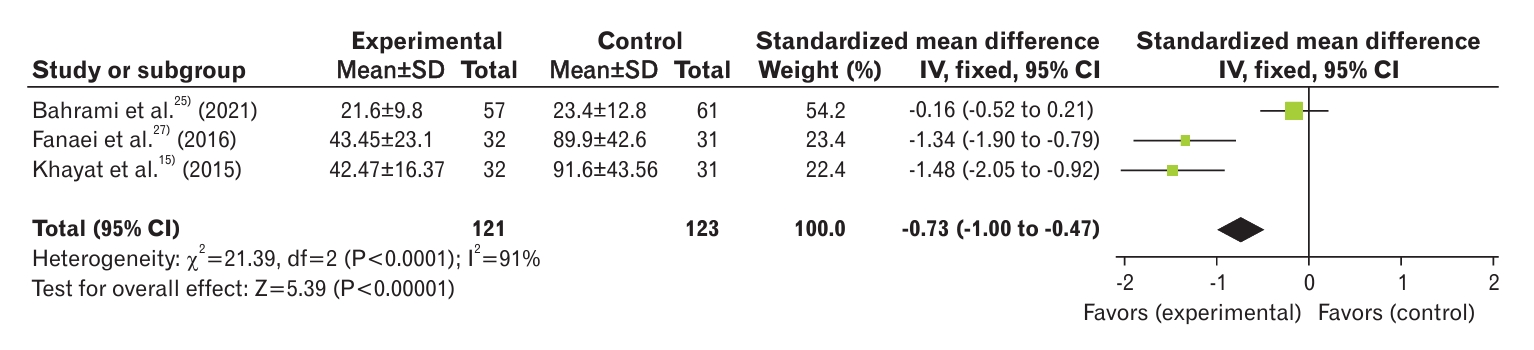

3. Severity of Premenstrual Syndrome

Three studies analyzed the severity of PMS in curcumin and control groups [15,25,27]. The results showed a significant decrease in PMS severity in the curcumin group compared with the control group (SMD, -0.73; 95% CI, -1.00 to -0.47; three studies) with high heterogeneity (I2=91%) (Figure 4). In the study by Bahrami et al. [25], the decrease in PMS intensity in the placebo group was as significant as that in the curcumin group. The results of this study showed no difference between the two groups in terms of reducing the severity of PMS symptoms, which resulted in high heterogeneity in our meta-analysis. To reduce the heterogeneity of the studies, the random effects model and sensitivity analysis were used. After removal of the paper of Bahrami et al. [25], there was 0% heterogeneity, and the groups were still significantly different (SMD, -1.41; 95% CI, -1.81 to -1.02; two studies) (Figure 5).

Forest plot of comparison of severity of premenstrual syndrome between curcumin and control groups. SD, standard deviation; IV, inverse variance; CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom.

4. Behavioral Symptoms of Premenstrual Syndrome

Two studies were included in this meta-analysis [15,27]. The results showed statistically significant differences between the groups regarding the behavioral symptoms of PMS (MD, -12.90; 95% CI, -17.82 to -7.99) with low heterogeneity (I2=0%) (Figure 6). On the other hand, the severity of behavioral symptoms in women with PMS was reduced after consumption of curcumin.

5. Mood Symptoms of Premenstrual Syndrome

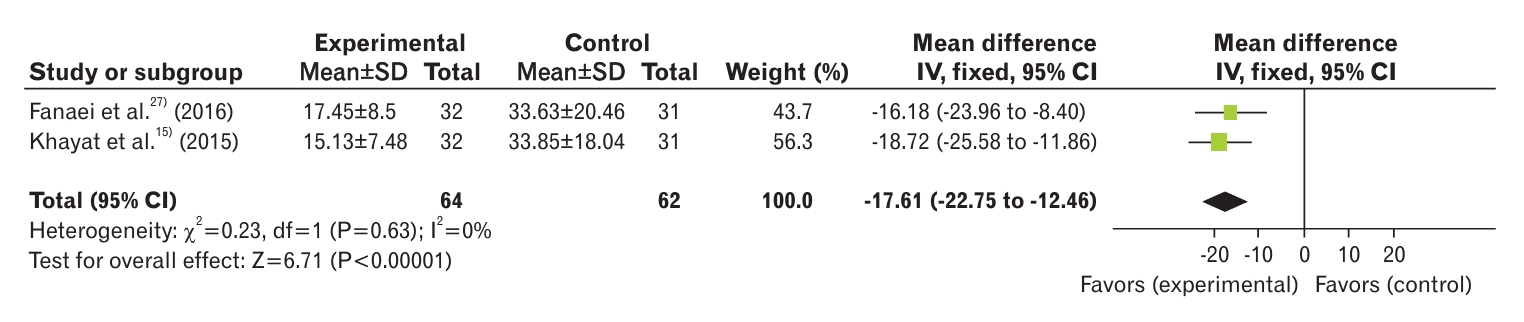

The results of the two included studies in this meta-analysis showed that the two groups were significantly different regarding mood symptoms of PMS (MD, -17.61; 95% CI, -22.75 to -12.46; I2=0%) (Figure 7) [15,27].

6. Physical Symptoms of Premenstrual Syndrome

The results of the two included studies showed a significant decrease in the MDs in physical symptoms after intervention (MD, -19.65; 95% CI, -25.50 to -13.80; I2=0%) (Figure 8) [15,27].

DISCUSSION

Among the wide variety of natural remedies, turmeric has profound medicinal value, and a large body of research has been conducted on this plant. This meta-analysis included five randomized controlled trials involving 379 women, which indicated that curcumin, a constituent of turmeric, significantly alleviated the severity of dysmenorrhea and PMS compared with placebo. Similarly, curcumin significantly reduced the symptoms of PMS (behavior, mood, and physical disorders).

The present study revealed that curcumin consumption immediately before or during menstruation could alleviate the severity of dysmenorrhea. Delgado et al. [29] in 2018 determined the minimal clinically significant difference in VAS score before and after treatment to be more than 1.4 cm in a 10 cm strip. In our study, the pain reduction rate was 1.25 cm with a 95% CI of 0.98 to 1.52, suggesting that curcumin may be clinically effective in the reduction of dysmenorrhea severity [29]. In line with the present study, limited systematic reviews conducted without undertaking meta-analysis have assessed the effect of curcumin on primary dysmenorrhea and PMS [14,30]. A meta-analysis in 2015 reported that extracts of the Zingiberaceae family (turmeric, ginger, etc.) are effective hypoalgesia agents, even safer than NSAIDs, and can decrease chronic pain [31]. These pain-relieving effects of curcumin are probably due to its anti-inflammatory properties, which down-regulate nuclear factor-kB, and cyclooxygenase 2 (Cox-2) [32]. In-vitro studies have demonstrated that curcumin has anti-inflammatory features by decreasing COX-2 expression and prostaglandin E2 release [33]. In laboratory conditions, curcumin has also been reported to have potential tocolytic effects on non-pregnant mice’s uterine contractions [34], confirming its effectiveness in inhibiting uterine contractions among women with dysmenorrhea.

Furthermore, the present study revealed that curcumin has therapeutic potential for ameliorating premenstrual symptoms. Recently, a systematic review examining the safety and therapeutic effects of Iranian herbal medicine for the treatment of PMS reported that curcumin is an effective and safe remedy for alleviating PMS symptoms [35]. PMS is characterized by physical, emotional, and behavioral symptoms that occur during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. It significantly disrupts women’s daily lives, including work and personal activities, and resolves itself automatically within a few days after the start of menstruation. The anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of curcumin make it a potential candidate for alleviating physical symptoms of PMS [30], while it influences the behavioral and emotional symptoms through its antidepressant actions (modulating the concentration of neurotransmitters, reducing inflammatory mediators, modulating hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal disorders, and reducing insulin resistance and oxidative stress substances) [36]. In a study on mice developing behavioral disorders, Abu-Taweel [37] in 2016 showed that curcumin had protective effects on social behavior and could prevent behavioral disorders. In an RCT, curcumin and ginger reduced the severity of psychological, behavioral, and physical symptoms of PMS, with curcumin exhibiting a more profound effect compared to ginger [16]. In two additional studies, the antidepressant effects of curcumin were comparable with the effect of famous antidepressant medications including to those of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (fluoxetine and imipramine) [38,39].

A potential limitation of the current study is the poor methodology used in most of the articles we examined. The small sample size, insufficient treatment allocation, imprecise method of blinding, and unspecified randomization technique used in these studies may all have affected the validity of the results. Although we performed a comprehensive search, our assessments may have been influenced by publication bias, which is a common drawback in most medical and health research [40], and this issue may be more pronounced in alternative medicine research [41]. Further research recruiting a larger number of participants from different socioeconomic backgrounds and testing different doses of herbal medicine for longer treatment periods, without the use of a placebo, is recommended to obtain more conclusive results regarding the effectiveness and safety of the tested herbal medicine. Another limitation of this study was that our search was limited to studies published in English.

In conclusion, the findings of our meta-analysis showed that using various forms of curcumin could reduce the severity of PMS and dysmenorrhea owing to its anti-inflammatory and antidepressant activities. Therefore, it could be regarded as an appropriate alternative for women with PMS and dysmenorrhea to improve their quality of life.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Acknowledgements

This study is the result of research project No. 50003124 approved by Student Research Committee, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran. We express our gratitude to the officials of the Clinical Research Development Center, Motazedi Hospital, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran.