|

|

- Search

| Korean J Fam Med > Volume 38(5); 2017 > Article |

Abstract

Background

The number of North Korean adolescent defectors entering South Korea has been increasing. The health behavior, including mental health-related behavior, and factors associated with depression in North Korean adolescent defectors residing in South Korea were investigated.

Methods

Data obtained from the Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-Based Survey (2011ŌĆō2014) dataset were utilized. In total, 206 North Korean adolescent defectors were selected, and for the control group, 618 matched South Korean adolescents were selected. Frequency analysis was used to determine the place of birth and nationality of the parents, chi-square tests were used to compare the general characteristics of the North and South Korean subjects, and multivariate logistic regressions were conducted to compare the health behavior of the two sets of subjects. To determine the factors associated with depression in the North Korean subjects, a logistic regression was performed.

Results

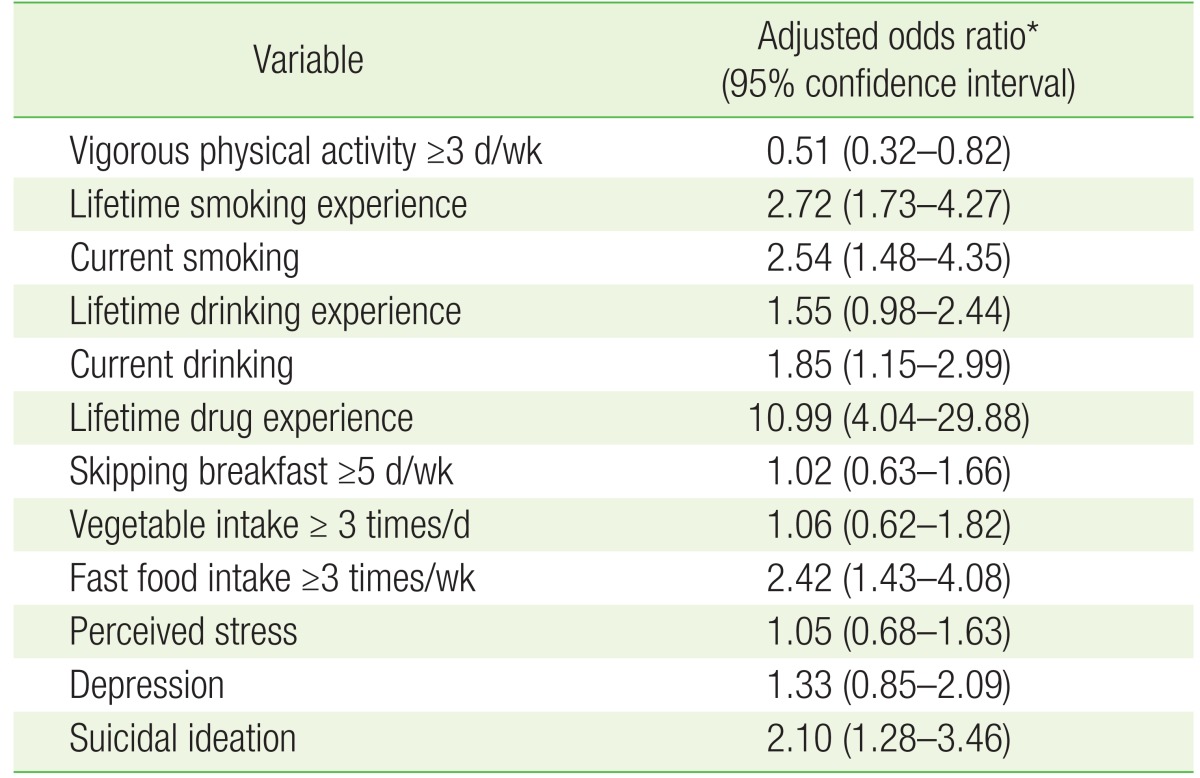

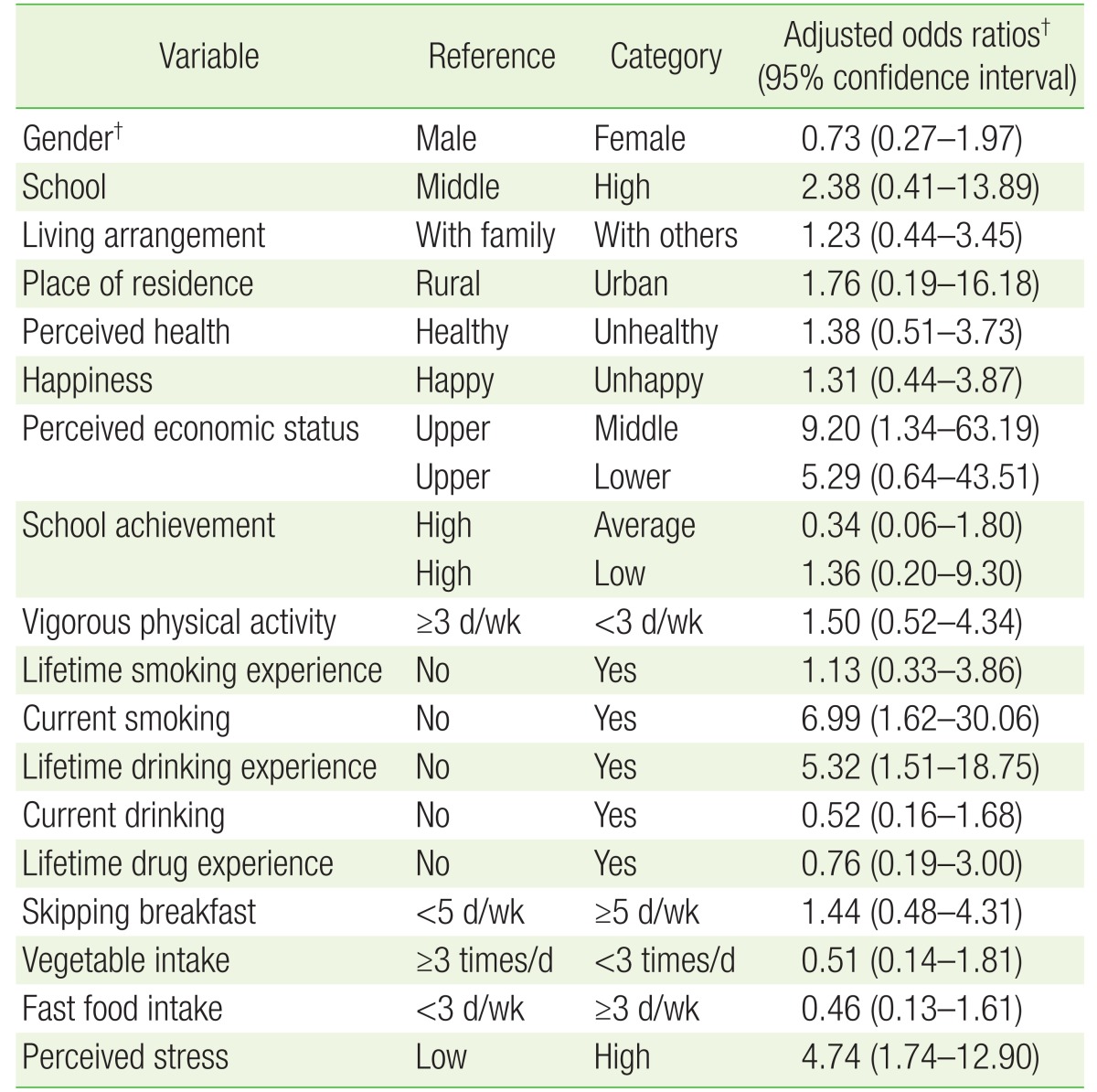

The North Korean adolescents reported higher current smoking (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.54; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.48 to 4.35), current drinking (aOR, 1.85; 95% CI, 1.15 to 2.99), and drug use rates (aOR, 10.99; 95% CI, 4.04 to 29.88) than did the South Korean adolescents. The factors associated with depression in the North Korean adolescents were current smoking (aOR, 6.99; 95% CI, 1.62 to 30.06), lifetime drinking experience (aOR, 5.32; 95% CI, 1.51 to 18.75), and perceived stress (aOR, 4.74; 95% CI, 1.74 to 12.90).

The number of North Korean defectors has been continually increasing ever since the North Korean famine of the mid-90s. The number of North Korean defectors entering South Korea was 100 in 1999, exceeding 1,000 in 2002, and exceeding 2,000 in 2006. By February 2007, the number of defectors exceeded 10,000, and by November 2010, it exceeded 20,000. However, since 2012, the number of North Korean defectors entering South Korea has been decreasing by 1,500 every year. According to statistics from the Ministry of Unification,1) the percentage of female entrants exceeded 50% in 2002, and in 2015, it exceeded 80% (1,025 out of the 1,276 entrants were female).

Since many North Korean female defectors enter South Korea with their children, the number of North Korean child and adolescent defectors has increased in proportion to the number of mothers entering South Korea. According to the 2014 statistics on North Korean adolescent defectors released by the Ministry of Education,2) the number of North Korean adolescent defectors has continued to increase. From among the total of 2,183 North Korean adolescent defectors, 1,128 attended elementary school (51.7%), 684 attended middle school (31.3%), and 371 attended high school (17.0%). The number of North Korean adolescent defectors born in countries other than North Korea and South Korea (third countries hereafter) was 979 in 2014; out of these, 594 attended elementary school (60.7%), 371 attended middle school (37.9%), and 14 attended high school (1.4%). According to a survey conducted by the North Korean Refugees Foundation,3) North Korean adolescent defectors came to South Korea to be with their families, to gain freedom, or to escape economic difficulties. North Korean adolescent defectors are likely to be vulnerable to various problems during the immigration process, such as family dissolution, mental health problems due to psychological trauma, family conflicts, and adaptation to the South Korean culture. According to Lee et al.,4) many North Korean adolescent defectors who are enrolled as students at Hanawon (Settlement Support Center for North Korean Refugees) suffer from posttraumatic stress disorder due to the psychological and emotional pressure they experience while entering South Korea. Furthermore, because of other problems like cultural differences, having missed school for long periods of time, age gaps between them and their classmates, and failure to adjust to the educational system, the dropout rate (2.5%) of North Korean adolescent defectors is far higher than the rate observed in typical South Korean adolescents (0.9%).2) According to one study conducted on North Korean adolescent and young adult defectors, anxiety and depression are related to their low quality of life.5) In another study that compared 102 North Korean adolescent defectors attending transitional school with 766 South Korean adolescents residing in the same region, the anxiety/depression score of North Korean adolescent defectors was higher than that of the South Korean adolescents.6)

In this study, we aimed (1) to comparatively analyze the general characteristics of North Korean adolescent defectors and South Korean adolescents, (2) to comparatively analyze the health behaviors of North Korean adolescent defectors and South Korean adolescents, and (3) to identify the factors associated with depressionŌĆöan index of overall mental healthŌĆöin North Korean adolescent defectors. Our ultimate purpose was to provide a foundation for the growth of North Korean adolescent defectors as sound South Korean citizens and to facilitate their adaptation to South Korean society.

This study used data from the 7th to 10th Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-Based Survey conducted between 2011 and 2014. This survey is an anonymous self-administered online survey that is conducted in order to analyze the health risk behavior of middle school and high school students in South Korea. The survey, a government-approved survey conducted on the basis of Article 19 of the Law for the Promotion of the Nation's Health, has been conducted annually since 2005 by the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Health and Welfare, and Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The subjects of this study were selected from among the 294,324 middle and high school students who participated in the above-mentioned survey. The survey participants comprised 206 North Korean adolescent defectors, 270,403 South Korean adolescents, and 23,715 adolescents from multicultural families (meaning neither South nor North Korean). Since there was missing data concerning the age of 75 (36.4%) of the North Korean adolescent defectors, 618 South Korean adolescentsŌĆöthree times the number of North Korean adolescent defectorsŌĆömatched for survey year and gender with their South Korean counterparts were selected. The selection was made by referring to Kim et al.7) The total number of subjects selected was 824.

According to Article 2.1 of the Act on the Protection and Settlement Support of Residents Escaping from North Korea, North Korean defectors are defined as those whose past addresses fall within the northern part of the military demarcation line (hereunder, North Korea), those who have or used to have spouses, workplaces, and family members in their direct line of descent in North Korea, and those who have escaped from North Korea with no foreign citizenship acquired in the new country of entry. The Ministry of Education, however, in the context of policies, defines North Korean adolescent defectors as ŌĆ£North Korean defectors born in North Korea, residing currently in South Korea, and aged between 6 and 24,ŌĆØ as well as ŌĆ£children and adolescents whose fathers and/or mothers are North Korean defectors and whose birthplace is a third country such as China (adolescents born in third countries).ŌĆØ Accordingly, to include North Korean adolescents born in third countries in the analysis, North Korean adolescent defectors were defined as those who responded with ŌĆ£North Korea,ŌĆØ to the question, ŌĆ£In what country was your father born?ŌĆØ or to the question ŌĆ£In what country was your mother born?ŌĆØ

Further, in the case of South Korean adolescents, in order to exclude adolescents from multicultural family backgrounds, those who responded with ŌĆ£South KoreaŌĆØ to both ŌĆ£In what country was your father born?ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£In what country was your mother born?ŌĆØ were defined as South Korean adolescents.

General characteristics included factors such as age, gender, height, weight, school, living arrangement, place of residence, perceived health, happiness, perceived economic status, and school achievement. Based on their living arrangement, the subjects were divided into those living with their family and those living with others (e.g., those living with relatives, in lodging accommodations, in dormitories, and in childcare centers). With regard to place of residence, counties, small/middle-sized cities, and large cities were all considered as urban areas. In the case of perceived health, those who viewed themselves as very healthy or healthy were categorized as healthy individuals. With regard to happiness, those who viewed themselves as very or somewhat happy were categorized as happy individuals, and were differentiated from those with lower levels of happiness. Perceived economic status and school achievement were divided into five categories, namely, upper, upper-middle, middle, lower-middle, and lower, and high, above average, average, below average, and low, respectively. Among these, upper-middle, middle, and lower-middle were redefined as middle for economic status and above average, average, and below average were redefined as average for school achievement, so that there were only three levels for each variable: upper, middle, and lower for economic status, and high, average, and low for school achievement.

The items regarding physical activity questioned the subjects about whether they engaged in vigorous physical activity at least three days a week. ŌĆ£Vigorous physical activity at least three days a weekŌĆØ implied that the survey participants engaged in at least 20 minutes of exercise that made them significantly breathless or sweat on at least three of the past seven days.

Tobacco smoking experience was divided into ŌĆ£lifetime smoking experienceŌĆØ and ŌĆ£current smoking.ŌĆØ Lifetime smoking experience was the category denoting that the individual had taken at least a couple of puffs on a cigarette in his/her lifetime. Current smoking was the category implying that the individual had smoked at least once in the past 30 days. With regard to drinking alcohol, the category ŌĆ£lifetime drinking experienceŌĆØ implied that the person had drunk at least one glass of alcohol in his/her entire life, and the category ŌĆ£current drinkingŌĆØ implied that the person had drunk at least one glass of alcohol in the last 30 days. Lifetime drug experience was the category used to describe individuals who had consumed cough medicines and expectorant agents in large quantities; had consumed nervous sedatives, stimulant drugs including butane gas and glue, methamphetamine, amphetamine, narcotics, and other drugs during their life to change their mood; and had had hallucinations, or had lost a substantial amount of weight on account of their drug/substance use.

With regard to items related to diet, ŌĆ£skipping breakfastŌĆØ implied that the person missed breakfast completely, or drank only milk or juice in the morning, for at least five of the past seven days. The variable ŌĆ£vegetable intakeŌĆØ was used to assess whether the individual ate vegetables as side dishes at least three times a day over the past seven days. The variable ŌĆ£fast food intakeŌĆØ meant that the person ate fast food such as pizza, hamburgers, and fried chicken at least three times in the past seven days.

The following variables related to mental health were also assessed. With regard to perceived stress, ŌĆ£high stressŌĆØ implied that the person felt considerably high or very high stress on ordinary days. The experience of depression was defined as having felt sad or hopeless to the extent that the individual could not continue his/her daily routine for two consecutive weeks during the past 12 months. Suicidal ideation was defined as having seriously considered suicide during the past 12 months.

Frequency analysis was conducted to analyze the parents' nationalities. The number of South Korean adolescents was three times that of the North Korean adolescent defectors, and the South Korean adolescents were matched with the North Korean adolescent defectors on survey year and gender. To compare the age, height, and weight of the North Korean adolescent defectors with those of the South Korean adolescents, independent samples t-tests were conducted, and to compare the other general characteristics and health behavior, chi-square tests were utilized. Moreover, after adjusting for gender, age, school, place of residence, perceived economic status, and school achievement, multivariate logistic regression analysis was conducted to obtain the odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the comparison between the health behavior of the North Korean adolescent defectors and that of the South Korean adolescents. To verify the factors associated with the North Korean adolescent defectors' experiences of depression, multivariate logistic regression analysis was conducted. The odds ratios and 95% CIs were calculated by means of the ENTER method, and the relevant variables were investigated. The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was also conducted. The results were deemed to be statistically significant when P<0.05. PASW SPSS ver. 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all the statistical analyses.

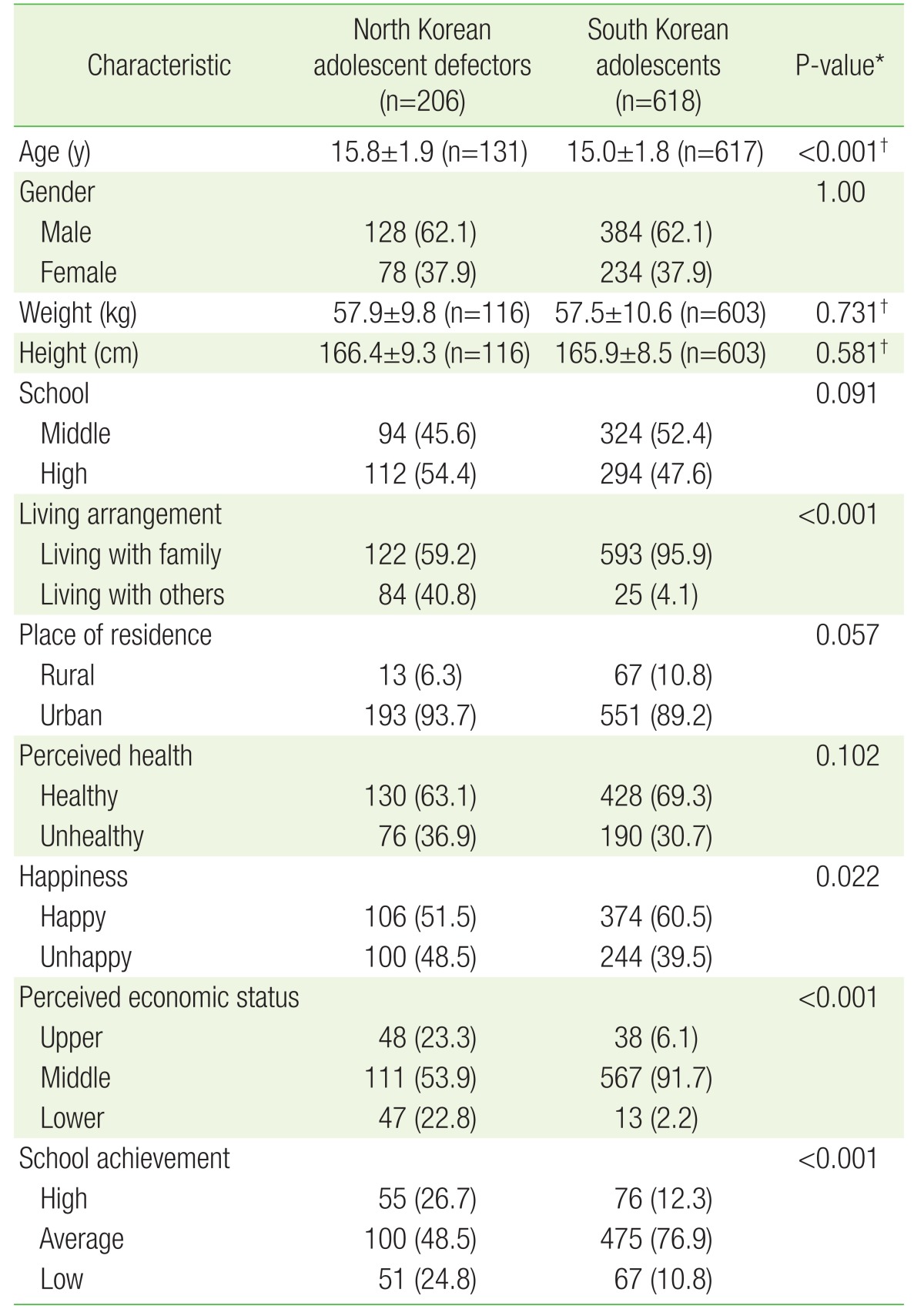

The demographic characteristics of the 206 North Korean adolescent defectors and 618 South Korean adolescents are shown in Table 1. There was a significant difference between the mean age of the North Korean adolescent defectors (15.8 years) and the mean age of the South Korean adolescents (15.0 years). The proportion of North Korean adolescent defectors who were living with their families was 59.2%, whereas most of the South Korean adolescents (95.9%) were living with their families. The proportion of North Korean adolescent defectors who felt happy was 51.5%, whereas the proportion of South Korean adolescents who felt happy was 60.5%. While most of the South Korean adolescents (91.7%) believed that they were middle class, only 53.9% of the North Korean adolescent defectors believed that they were middle class. Regarding school achievement, 26.7%, 48.5%, and 24.8% of the North Korean adolescent defectors believed that their academic achievement was high, average, and low, respectively, whereas 12.3%, 76.9%, and 10.8% of the South Korean adolescents believed that their academic achievement was high, average, and low, respectively.

Table 2 shows the difference in health behavior between the North Korean adolescent defectors and South Korean adolescents. There was a significant difference between the two groups with respect to health behavior, with the exception of skipping breakfast, vegetable intake, and perceived stress. North Korean adolescent defectors reported a higher rate of current smoking, current drinking, lifetime drug experience, depression, and suicidal ideation than did the South Korean adolescents.

Table 3 presents the results of multivariate logistic regression, which shows the odds ratios of health behavior for the North Korean adolescent defectors compared to those for the South Korean adolescents. The North Korean adolescent defectors were 2.72 times more likely to have had a lifetime smoking experience (95% CI, 1.73 to 4.27) and 2.54 times more likely to be smoking (95% CI, 1.48 to 4.35) than were the South Korean adolescents. The North Korean adolescent defectors were also 1.85 times more likely to be drinking (95% CI, 1.15 to 2.99) and 10.99 times more likely to have had a lifetime drug experience (95% CI, 4.04 to 29.88) than were the South Korean adolescents. Further, the North Korean adolescent defectors were 2.10 times more likely to have had suicidal ideation (95% CI, 1.28 to 3.46) than were the South Korean adolescents.

With regard to the factors related to depression for the North Korean adolescent defectors, the results of the multivariate logistic regression analysis are presented in Table 4. According to the Hosmer-Lemeshow test, the model showed no evidence of lack of fit (P=0.81). Among the North Korean adolescent defectors, the current smokers had had a depression experience 6.99 times more than the non-smokers (95% CI, 1.62 to 30.06). Furthermore, the depression experience was 5.32-fold higher when the North Korean adolescent defectors had had a lifetime drinking experience (95% CI, 1.51 to 18.75). The North Korean adolescent defectors who felt a great deal of stress had had a depression experience 4.74 times more than those who did not (95% CI, 1.74 to 12.90). With regard to the other variables, there was no statistical significance between the North Korean adolescent defectors and the South Korean adolescents.

Most North Korean child and adolescent defectors take the preliminary education course at Hanawon (Settlement Support Center for North Korean Refugees) immediately after entering South Korea. After completing the course, those who are at the age appropriate for middle or high school take a six-month to one-year transitional education course at Hangyeore School, after which they complete the resettlement schooling program (at regular or alternative schools).8) According to the 2014 statistics provided by the Ministry of Education, a total of 2,183 North Korean adolescent defectors reside in South Korea, and 1,055 of them attend middle and high schools.2) In this study, the number of North Korean adolescent defectors was 206, and this number accounted for 19.5% of all North Korean adolescent defectors in South Korea. This study compared the characteristics of North Korean adolescent defectors attending regular middle or high schools and those of South Korean adolescents, with the aim of uncovering the factors related to the depression of North Korean adolescent defectors.

The odds of current smoking, current drinking, and lifetime drug experience were higher in the North Korean adolescent defectors than in the South Korean adolescents, which corresponds to the findings of previous research.7) According to the World Health Organization's data on worldwide tobacco smoking,9) 43.9% of adult men in North Korea smoke every day; thus, the relatively high smoking rates of North Korean adolescent defectors could have been influenced by the high smoking rates of their parents from North Korea.7) Chang et al.10) reported that the risk of alcohol consumption in adolescents increased when their stress levels were high, when they had experienced depression, when they had experienced suicidal ideation, and when their perceived levels of happiness were low. Further, the risk of alcohol consumption also increased when the adolescents smoked or had used drugs. Such findings may be applicable to the North Korean adolescent defectors in this study. With regard to lifetime drug experience, the odds were 10.99 times greater in North Korean adolescent defectors than in South Korean adolescents. North Korea is known to produce drugs and sell them in other countries in order to earn revenue. Therefore, it is possible that North Korean adolescent defectors resort to drug smuggling to support themselves while leaving the country.11)

With regard to the mental health-related variables, the North Korean adolescent defectors showed higher levels of perceived stress, depression, and suicidal ideation than did the South Korean adolescents. Depression is a general term, which includes a range of feelingsŌĆöright from sadness, misery, and disappointment, to self-blame, despair and hopelessnessŌĆöand an intense sense of aggression directed toward the self (or a part of the self). It can be experienced in varying degrees of severity and duration throughout the course of a person's life. The extreme form of depression (in terms of degree) is clinical depression.12) According to the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition (American Psychiatric Association),13) the diagnostic criteria for a major depressive episode include change in sleep and suicidal ideation, or a plan or attempt to commit suicide. In other words, among the above-mentioned mental health-related variables, depression is the most comprehensive variable; thus, the present study focused on the depression of North Korean adolescent defectors.

In the regression analysis conducted to uncover the factors related to the North Korean adolescent defectors' experiences of depression, three significantly related variablesŌĆöcurrent smoking, lifetime drinking experience, and perceived stressŌĆöwere identified. These results were similar to the findings of previous studies on adolescent depression in South Korea.14,15)

A previous study on depression among young North Korean defectors revealed that it was highly probable that they would suffer depression in the early stages of resettlement, that is, within one year of entering South Korea.5) The study also revealed that the prevalence of depression in North Korean adolescent and young adult defectors was similar to that in the general South Korean population. On the other hand, the North Korean adolescent defectors assessed in this study had been in South Korea for over a year after entering South Korea, in accordance with the general settlement process, and a higher percentage of them than the South Korean adolescents had experienced depression. This trend seems to be associated with stress in everyday life, which arises from difficulties in school, cultural difficulties, language problems, and the fact that the education that the North Korean defectors receive in South Korea does not often correspond to their actual ages.

In a study investigating factors affecting depression in South Korean high school students, female students were 1.52 times more likely than male students to be depressed.14) Park and Sohn15) also reported that the female gender was associated with a greater prevalence of depression in South Korea. Furthermore, Kim and Shin16) reported that the levels of posttraumatic stress and unease were higher among female North Korean adolescent defectors than among their male counterparts. In this study, however, the prevalence of depression did not significantly differ according to gender in the North Korean adolescent defectors. This could be influenced by the fact that the number of female subjects was 78, accounting for only 37.9% of the North Korean adolescent defectors.

This study has several limitations. First, our study was based on cross-sectional data obtained from the Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-Based Survey conducted between 2011 and 2014, and causality has not been clarified. Second, the North Korean adolescent defectors for whom age-related data was missing could have been over 19 years, which may have led to the misinterpretation of the results. Third, the number of North Korean adolescent defectors born in third countries is gradually increasing,2) and linguistic and cultural differences exist between North Korean adolescent defectors born in third countries and those born in North Korea. Since the present study examined the characteristics of North Korean adolescent defectors without considering such differences which could have affected the results of the study. Thus, future studies would need to classify North Korean defectors according to their country of birth. Fourth, although differences in adaptation or satisfaction, based on the length of residence in South Korea, were observed in a previous survey on North Korean defectors,3) information on the North Korean adolescent defectors according to their country of entry could not be obtained. Fifth, the study subjects do not represent all the North Korean adolescent defectors living in South Korea. Although it is assumed that the North Korean adolescent refugees who do not attend a school may experience more stress,6) they could not be included in the study due to the nature of the data.

This study is significant in that it comparatively analyzed the health behavior, including mental health-related behavior, of North Korean adolescent defectors attending regular schools and the corresponding behavior of South Korean adolescents, and identified the factors associated with depression, which can serve as an overall index of mental health, in North Korean adolescent defectors. The health behavior and depression of North Korean adolescent defectors involved more negative elements than was the case in the health behavior and depression of South Korean adolescents; thus, management plans seeking to enhance the adjustment of North Korean adolescent defectors may need to address issues related to smoking, drinking, drug use, and depression among North Korean adolescent defectors. Various support measures for North Korean adolescent defectors, that tackle the areas of lifestyle modification, education, and mental health are necessary to promote their adaptation to South Korean society.

References

1. Ministry of Unification. North Korean refugees and resettlement [Internet]. Seoul: Ministry of Unification; 2016. [cited 2016 Jan 31]. Available from: http://eng.unikorea.go.kr/content.do?cmsid=3026

2. Ministry of Education. Statistics of North Korean defector student, 2014 [Internet]. Sejong: Ministry of Education; 2014. [cited 2015 Feb 8]. Available from: www.moe.go.kr/web/100026/ko/board/view.do?bbsId=294&encodeYn=Y&pageSize=10&boardSeq=55691¤tPage=7&mode=view

3. North Korean Refugees Foundation. 2014 Survey for the North Korean adolescent refugees. Seoul: North Korean Refugees Foundation; 2014.

4. Lee IS, Park HR, Kim YS, Park HJ. Physical and psychological health status of North Korean defector children. J Korean Acad Child Health Nurs 2011;17:256-263.

5. Choi SK, Min SJ, Cho MS, Joung H, Park SM. Anxiety and depression among North Korean young defectors in South Korea and their association with health-related quality of life. Yonsei Med J 2011;52:502-509. PMID: 21488195.

6. Lee YM, Shin OJ, Lim MH. The psychological problems of North Korean adolescent refugees living in South Korea. Psychiatry Investig 2012;9:217-222.

7. Kim H, Han MA, Park J, Ryu SY, Choi SW. Health behavior of North Korean, multicultural and Korean family adolescents in Korea: the Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey, 2011-2013. Health Policy Manag 2015;25:22-30.

8. Ministry of Education. Plan for support of educating North Korean defectors, 2015 [Internet]. Sejong: Ministry of Education; 2015. [cited 2015 Mar 7]. Available from: http://www.moe.go.kr/web/106888/ko/board/view.do?bbsId=339&boardSeq=58635

9. World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2015. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

10. Chang D, Kim H, Cha S, Choi H, Lee E. Factors associated with drinking and problem drinking among Korean adolescents: using the 2013 Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey (KYRBS) data. Health Serv Manag Rev 2015;9:27-36.

11. Kim SH, Choi JY, Lee YH. The theoretical review on cause and real condition of crimes by North Korean defectors. J Peace Unification Stud 2015;7:49-94.

12. Briggs S. Risks and opportunities in adolescence: understanding adolescent mental health difficulties. J Soc Work Pract 2009;23:49-64.

13. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. Arlington (VA): American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

14. Son SY. The study on predictors of depression for Korean high school students. J Korea Soc Wellness 2012;7:97-106.

15. Park E, Sohn S. The relating factors on depression among adolescents in South Korea. J Korean Soc Sch Health 2009;22:85-95.

Table┬Ā1

Demographic characteristics of North Korean adolescent defectors and South Korean adolescents

Table┬Ā2

The difference in health behavior between North Korean adolescent defectors and South Korean adolescents

- TOOLS