INTRODUCTION

Ependymomas are rare primary tumors of the cranial nervous system (CNS) and can occur in any age group [1]. In children, while 90% of the tumors affect the brain, only 10% originate from the spine. Ependymoma is a slow-growing tumor that tends to displace adjacent structures. It can occur in any part of the CNS, and the manifestation of its symptoms usually correlates to the tumor location. Spinal cord tumors can present with low back pain, sciatica, and weakness [2]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumors, the four types of ependymal tumors are subependymoma WHO grade I, myxopapillary ependymoma WHO grade I, ependymoma WHO grade II, and anaplastic ependymoma WHO grade III [3].

Back pain and lower limb weakness are the most common symptoms in spinal ependymoma [1], followed by sensory dysfunction related to urinary and bowel impairments [4]. Owing to the rarity of its incidence in children and its often ill-defined clinical feature, ependymoma poses a great challenge in terms of clinical suspicion and detection, especially at the early stage when its clinical presentation lacks specificity. The challenge in primary care is enhanced when chronic lower back pain is prevalent and often considered self-limiting and non-life-threatening. Chronic lower back pain can mask potential underlying causes and can easily be mismanaged. Therefore, primary care physicians tend to continue symptomatic treatment and innocently disregard ependymoma as the potential differential diagnosis. Delayed diagnosis leads to progression of neurological deficits, increases the risk of surgery-related complications, and ultimately poses poor morbidity after surgery.

This case report describes an unfortunate case that demonstrates the need for primary care physicians to be vigilant and to raise their suspicion index for early symptoms of ependymoma in young adults presenting with chronic low back pain.

CASE REPORT

A 14-year-old girl, accompanied by his father, presented to a university primary care clinic with a complaint of intolerable low back pain after two recent falls. On further history taking, she had been experiencing a chronic back pain for the last 2 years. She described her initial pain to be acute in onset, occurring at the lower back because of prolonged sitting on the floor, after which she had an ongoing chronic low back pain. In her current boarding school training, children were accustomed to be sitting on the floor for many hours to learn the Koran.

She could perform her daily activities but distanced herself from any sports. Having developed increasing pain in her back, she requested her father to take her to a general practitioner (GP), which required her to be excused from school activities. Hence, her father became suspicious of her real intention and attributed her complaint of pain to the secondary intention of wanting to be away from school. Her father, who had a strong character, dominated the consultation and tried to convince the physician to the idea that his daughter feigned the back pain as an excuse to be away from school.

Over the last 24 months, she had visited multiple GP clinics. Her recurrent clinic visits were initially driven by symptoms of low back pain, sciatica, and later, lower limb numbness and weakness. The latter was noticeable 21 months after the first clinic visit. On recalling her history, she revealed four crucial time points at which she sought medical help for symptom progression. Most of the time, she was attended by different physicians during her clinic visits. The GP whom she visited several times gathered information on her history mainly from her father, who downrated and attributed her symptoms to prolonged sitting with lack of stretching.

Her first clinic visit was at 12 years of age for a complaint of intermittent low back pain without neurological deficit. A diagnosis of nonspecific low back pain was made, and a paracetamol with topical ointments was prescribed.

Approximately 18 months later, at the age of 13 years, she started to experiencing persistent low back pain, for which she visited the GPŌĆÖs clinic on a monthly basis. The pain started to radiate to the right lower leg on walking. At that time, she could still maintain her schooling and other activities of daily living. Her symptoms were treated conservatively as muscular pain and sciatica. No radiological imaging was ordered at that time. Continuous analgesia, topical ointment, and multi-vitamins were prescribed by different GPs.

Three months later, she started to develop persistent weakness and numbness on her right lower limb, especially on sitting. This was worsened by lifting objects and ambulation. A diagnosis of sciatica was consistently made by her physicians. Management of her condition remained conservative with regular analgesia and back care. In addition, multiple medical leave certificates were issued, which her father disliked.

Three months later, when she was 14 years old, she visited our primary care center with a severe low back pain triggered by two incidents of fall in the bathroom. The pain disturbed her sleep, and her right lower limb weakness and numbness worsened. She was unable to ambulate well. On examination, she walked with antalgic gain due to pain. No spinal tenderness was elicited upon palpation, but paraspinal muscle stiffness was observed. Her lumbar spine range of motion was restricted at 45┬░ on forward flexion. Straight leg raising was up to 45┬░ bilaterally, with evidence of nerve root tension. Sacroiliac and hip joint dysfunction test results were negative. A neurological examination of her lower limbs revealed a depressed deep tendon reflex in both knees. Her muscle strength was graded 4/5 on hip flexion, knee flexion, and extension, but was slightly weaker on the right side. Her tone was normal bilaterally. She felt patchy reduced sensation to light and sharp touches in the right lower limb at L2 to L5 dermatomes. No saddle paresthesia was observed. A lumbosacral radiograph showed loss of normal lumbar lordosis.

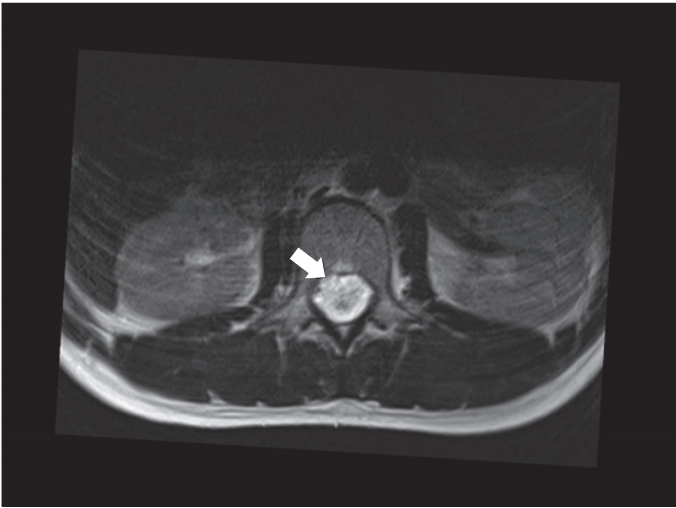

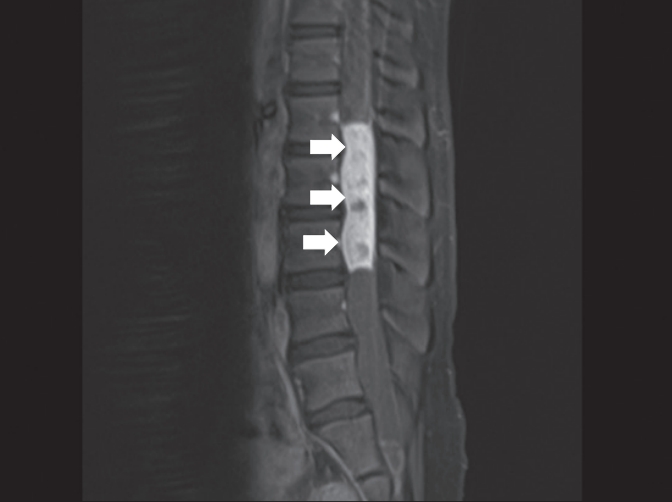

Our primary care center, located within a university-based hospital, provides an added advantage of direct access to advanced radiological services. We liaised with the radiologist who suggested performing magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spine urgently. Upon detection of the spinal lesion, a contrast medium was administered during the MRI. An immediate report revealed an enhancing spinal mass in the region of the conus medullaris, which suggested an ependymoma as shown in Figures 1 and 2.

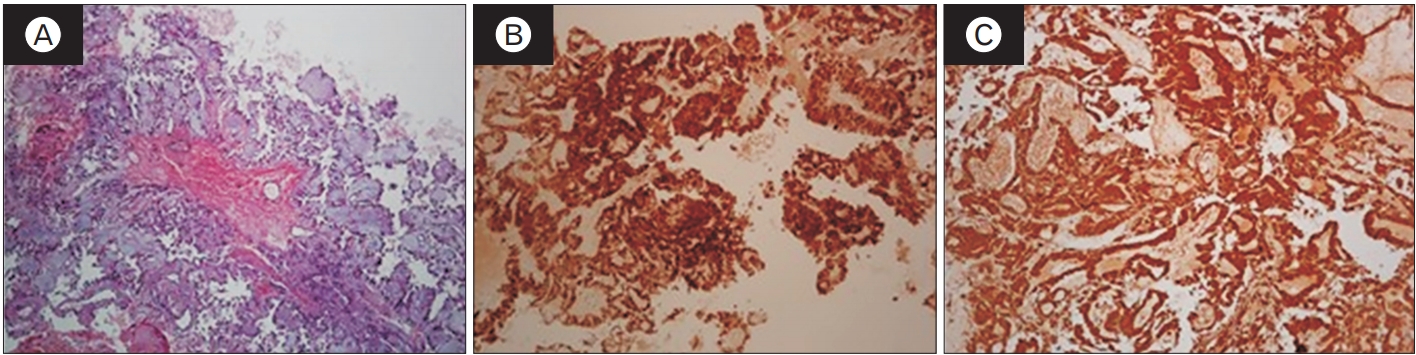

Subsequently, she underwent L1 to L3 laminectomy and gross tumor excision. Histopathological examination (HPE) of the spinal mass showed features consistent with ependymoma WHO grade II as shown in Figure 3. After the surgery, her right-sided lower limb weakness improved tremendously. However, she developed bladder and bowel dysfunctions, which are possible complications of any spinal cord surgery. Assessment by a rehabilitation specialist revealed a significant neurogenic bladder on the basis of the failed trial without a catheter. Further evaluation using single-channel cystometry revealed detrusor acontractility with high residual volume. The 4-hourly, clean, intermittent, self-catheterization residual volume was >20%. A bowel assessment revealed an upper motor neuron type of neurogenic bowel. Five months after the surgery, her neurogenic bladder and bowel remained. She needed regular rectal enema with manual evacuation to empty her bowel. Moreover, she needed to perform 4-hourly intermittent self-catheterization to empty her urinary bladder. While her right lower limb and saddle paresthesia only gradually improved, her lower limb weakness completely resolved.

The patient provided written informed consent for the publication of clinical details and images.

DISCUSSION

Unlike intracranial ependymoma, spinal cord ependymoma is uncommon in children, accounting for 10% to 13% of all ependymomas [2,5]. The present case is a confirmed classic ependymoma WHO stage II in the conus medullaris region, as evident in the MRI and HPE findings [1].

In ependymoma, generally, early symptoms are clinically mild. Most patients could walk independently without objective evidence of neurological deficits, which often lead to delayed diagnosis. In the later stages, pain is the most common presenting symptom [1,4-6]. Additional accompanying symptoms are common and location dependent, correlating to the original location and displacement of the tumor [1]. In our case of ependymoma originating from the conus medullaris, low back pain was the initial presenting symptom, which then progressed to sciatica. The additional symptoms commonly cited in spinal ependymoma in general are motor weakness, spasticity, and sensory impairment involving the bladder and bowel dysfunction [4]. On average, the symptoms can be present for 16 to 22 months prior to diagnosis and treatment, respectively [4,6]. In our case, the diagnosis was made 24 months after commencement of the intermittent low back pain.

Spinal ependymoma presenting with acute intermittent and chronic low back pain has been reported in the primary care setting. Ngo et al. [7] reported the case of a 19-year-old man with myxopapillary ependymoma of the L2ŌĆōL4 regions who presented with an intermittent, non-troubling low back pain for 3 years. An initial referral to an orthopedic surgeon was made on the basis of the recurrent low back pain, which was symptomatically managed. However, appearance of a neurological deficit such as erectile dysfunction 1 year later prompted another referral to an orthopedic surgeon. The low back pain was initially attended by primary care physicians. Referral and further imaging were initiated on the basis of the chronic intermittent lower back pain, worsening of the low back pain, and new neurological deficits [7]. These findings are similar to the clinical progression in our case. The acute exacerbation of the lower back pain triggered further investigations, which led to the diagnosis [6].

In our case, the patient had delayed assessment for diagnostic imaging. She had no noticeable progression of back pain from localized low back pain to sciatica, which was missed by the GPs. It was not until she had a fall that the pain was exacerbated at an uncontrollable rate that caused concern to her parents and a red flag sign to the physician; thus, urgent MRI was initiated. This could be attributed partly to three important factors. First was the downrating of her low back pain by her father, who attributed the pain to her intent to attain social gain. Second was the deficiency of the GPs to fully assess adolescent patients for more-confirmatory sign and symptoms. A more delicate issue in this case was on important history taking from adolescents, which could be difficult when adolescents are not cooperative. In addition, parents might significantly mask the real history when they dominate the consultation. Using a few special techniques to communicate with adolescents effectively, for example, by having part of the visit consultation without the parents being present can yield successful history taking [8]. Third, having many different GPs examining the patient could have contributed to the lack of continuation of care, which resulted in the inability to monitor the progression of back pain and ultimately delayed the initiation of further investigations.

Recovery of patients with spinal ependymoma is dependent on the extent of the neurological symptoms at presentation. Children who presented with good neurological function preoperatively tended to maintain neurological function after surgery [4]. In our case, after surgery, no gross motor impairment occurred. The patient could walk independently. However, the newly developed neurogenic bladder and bowel suggest the presence of some damage to the sciatic nerve during the surgical procedure for tumor removal. This led to the need for intermittent self-catheterization and use of rectal enema and manual evacuation of bowel. Five months after surgery is too early to suggest permanent disability. Intensive rehabilitation is key, as patient symptoms could still have time to improve because 2 years of rehabilitation therapy is needed before symptoms start to plateau. Meanwhile, intermittent self-catheterization of the urinary bladder can potentially pose severe reduction in quality of life. Especially for adolescents, this can lead to reduced social interaction [9] and depression [10].

In the primary care setting, a high index of suspicion is needed to determine the pathological cause in young adults with chronic lower back pain. This case demonstrates the importance of clinical examination and continued vigilance for pain progression and neurological deterioration in young adults with low back pain to detect the early stage of ependymoma. After surgical resection of the tumor, long-term follow-up is important especially when neurological impairment is present. This is so that continuous support and measures can be executed to manage its associated complications. The multidisciplinary team involvement in this case highlights the significant role each specialty plays, from the time of diagnosis up to the time of follow-up.