INTRODUCTION

Since the first century B.C., humans have smoked cigarettes; this has become widespread in the 20th century when tobacco production grew robustly. In Korea, it has only been about four centuries since cigarettes came in 1616, after the Japanese Invasion of Korea in 1592, according to the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty, and it became widely used. As of 2016, the overall smoking prevalence (among those >15 years) in South Korea was 33.5% in males and 8.8% in females [

1].

As it is well known, tobacco use is the worldŌĆÖs ŌĆ£leading preventable causeŌĆØ of death today. Globally, people suffer from tobacco-related health problems, such as cardiovascular diseases, stroke, lung cancer, and other respiratory diseases that lead to death in serious cases, which will continue to occur in the future [

2].

The World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, ŌĆ£the first international treatyŌĆØ with legislative effects on public health, was enrooted in 2003 and has evolved since then [

3]. Such and other regulatory actions were mostly effective on smokersŌĆÖ behavior mirrored by socioeconomic indicators. The figures related to cigarette smoking have been useful for authorities to establish tobacco product regulation policies to prevent the excessive economic cost of tobacco use and other secondary socioeconomic losses [

4].

Various regulations have put tobacco companies on the brink of existence, and they have begun to use new strategies for their own survival. Novel tobacco products have landed on the market with shrewd tactics, being ŌĆ£fancyŌĆØ contour and hyped up as lesser harmful than conventional ones, thereby enticing smokers using conventional cigarettes (CCs) into having hands on them with or without hope of smoking cessation. Novel tobacco products include electronic cigarettes or e-cigarettes (ECs), and heated tobacco products (HTPs). EC is an electronic device that applies heat to a solution that dissolves nicotine in a particular solvent using its own battery and vaporizes it, which makes users inhale. HTP is a hybrid form of CC and EC that heats a uniquely designed cigarette up to 350┬░C (lower than CC), vaporizes, and delivers it to users [

5]. In South Korea, the worldŌĆÖs second largest market for HTPs, HTP has been expanding its market share since 2017, after EC was briefly introduced and before going off the market. A substantial proportion of polytobacco use has been reported around the same time [

3].

The tobacco market in South Korea has been facing changes since the introduction of novel tobacco products. Smoking rate is in line with cigarette sales in South Korea, which is usually the lowest in the first quarter of every year and increases until the next year. In other words, the rate increases when sales rise and tends to decrease when the sales reduce. Contrary to previous trend, the decline in tobacco sales has slowed gradually and then turned into an uptrend since 2020, with the appearance of novel tobacco products. Furthermore, the number of visits to smoking cessation clinics decreased during the same period [

4]. Novel tobacco products have also changed the behavior of tobacco users. People who switched from CCs to HTPs had less intention to quit tobacco than CC users, as documented in previous studies [

4,

6]. It has been demonstrated that polytobacco users were more dependent on nicotine and less willing to quit tobacco use than sole users [

7].

This study aimed to verify the results of previous studies using a representative sample, the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES). It represents the general health behavior and nutritional status of Koreans and is indicative of tobacco use status. We attempted to substantiate two points: whether dual users are highly dependent on nicotine in terms of the amount of tobacco use and time to first cigarette (TTFC) or stick, and whether their intention to use tobacco decreases, as expressed by the proportions of an attempt to quit using tobacco over the past year and the preparation stage of tobacco cessation.

METHODS

1. Research Scheme and Data Collection

Raw data from the eighth KNHANES 2019, run by the Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention (currently Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency) were used in this study. As a representative database of the overall population of South Korea, the data were sampled using complex cluster sampling with two-stage stratification. We found the total number of KNHANES respondents to be 8,110. Surveys of novel tobacco products have been conducted since 2011 for ECs and 2019 for HTPs. This study was exempted by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital (2107-183-1237) because the KNHANES is open to the public. The personal identifiers of all study participants were de-identified. The requirement for obtaining informed consent was waived.

2. Setting Eligibility Criteria

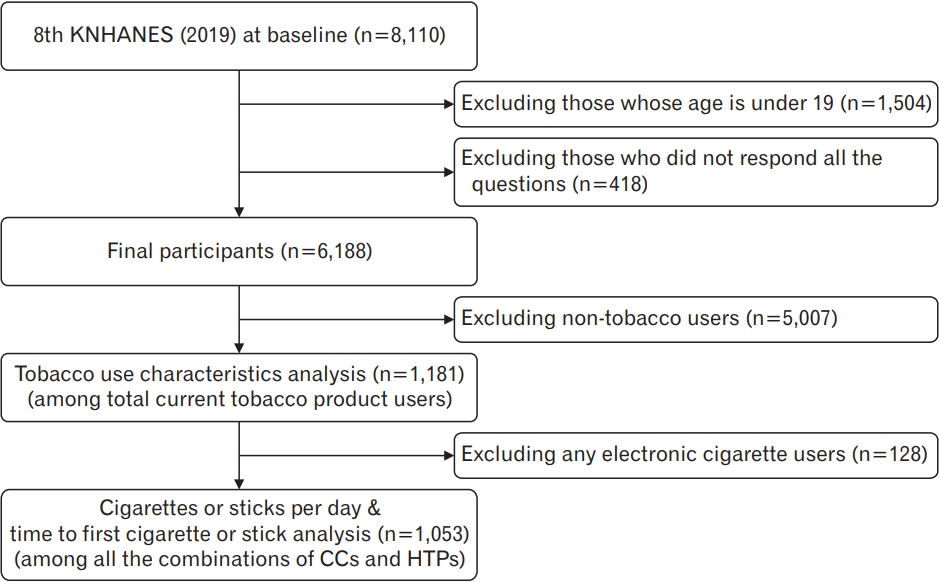

Of the 8,110 respondents in the baseline data, those who were 19 years of age at the time of the survey (n=1,504) and did not complete the questionnaire (n=418) were excluded from the study (

Figure 1). Finally, 6,188 participants were included in the study. The participants were divided into various groups, depending on whether they used tobacco products, and if so, what kind of products they used.

3. Definition of Variables

We used the term ŌĆ£userŌĆØ instead of ŌĆ£smokerŌĆØ for tobacco use, considering that existing smoking terms do not fully reflect the use of novel tobacco products; for example, vaping and heating are differentiated from smoking. Tobacco use status among different types of products was classified into three groups: current, former, and never users, including smokers, as mentioned in a previous study [

8]. In the case of CCs, current and former smokers were defined as those who smoked more than five packs (equivalent to 100 cigarettes) in their lifetime, but they were sorted according to whether they smoke or not at the time of the survey, i.e., ŌĆ£yesŌĆØ for the current smokers and ŌĆ£noŌĆØ for the former ones. Current smokers were subdivided into daily and intermittent users, depending on the frequency of use, especially for dual users, in a similar manner according to a study by Borland et al. [

9].

This description was also applied to ECs and HTPs, albeit with slightly different definitions. Lifetime experience with ECs and HTPs was defined as not equal to CCs, but ŌĆ£ever-use in their lifetimeŌĆØ and so was current experience as ŌĆ£ever-use in the past one monthŌĆØ at the same period. Former users were those who answered ŌĆ£not applicableŌĆØ in current use for EC users and did so in the same way as CC for HTP users.

We first defined new terms ŌĆ£total current tobacco product usersŌĆØ and ŌĆ£non-tobacco users,ŌĆØ as mentioned in the following: All current tobacco users, including CCs, ECs, and HTPs were defined as total current tobacco users (n=1,181), and former (n=1,228) and never (n=3,779) users, as non-tobacco users (n=5,007).

The combinations of current tobacco product users were indicated as follows: any users were defined as those who currently use at least one type, single users for only one type, dual users for two types, and triple users for all three types of products. Each group was represented by the following terms: ŌĆ£any CC,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£any EC,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£any HTPŌĆØ for any users of each type, ŌĆ£CC only,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£EC only,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£HTP onlyŌĆØ for single users of it and ŌĆ£CC+HTP dual,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£CC+EC dual,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£EC+HTP dual,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£CC+EC+HTP tripleŌĆØ for redundant users. The ŌĆ£+ŌĆØ sign between the letters stands for combination.

4. Tools for Tobacco Use and Cessation Behavior

Targeted for all current tobacco product users, we analyzed tobacco use and cessation behavior using several measures. First, as indices of nicotine dependence, the terms cigarettes per day (CPD) and TTFC in the morning in the Fagerstr├Čm Test for Nicotine Dependence were used with slight modifications to the definition in the study, reflecting changes in tobacco use behavior: CPD as cigarettes or sticks per day and TTFC as time to first cigarette or stick in the morning. They were applied only to the CC and HTP users, and not the EC users because of the absence of a measure for them. Cigarettes or sticks per day were divided into four groups: Ōēż10, 11ŌĆō20, 21ŌĆō30, and >30 cigarettes or sticks. TTFC was split into four groups: 5 or less, 6 to 30, 31 to 60, and more than 60 minutes (1 hour). Both tools were evaluated through respondents answering the question, ŌĆ£How many cigarettes or sticks do you use per day?ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£How long does it take to use your first cigarette or stick in the morning?ŌĆØ

Second, attempts and motivation to quit using tobacco were assessed using a transtheoretical model for those who responded to the question, ŌĆ£Have you ever ceased to use tobacco for more than a day (24 hours) with the intention of quitting in the past year?ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£Do you have any plan to quit using tobacco in the next month?ŌĆØ Answers were distinguished by ŌĆ£yesŌĆØ or ŌĆ£noŌĆØ for the first one and ŌĆ£within 1 month,ŌĆØ ŌĆØwithin 6 months,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£not within 6 months, but someday,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£not at all at the moment,ŌĆØ for the other one, which is thought to be a ŌĆ£preparation stage (only for the first option)ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£others (including the others), respectively.

5. Sociodemographic Characteristics

As shown in

Table 1, sociodemographic factors, such as age, gender, residential area, educational level, occupation, household income, marital status, and frequency of alcohol consumption were included in the analysis. Household income was divided into quartiles as follows: ŌĆ£Low (less than 1 million in South Korean won [KRW])ŌĆØ for the first, ŌĆ£middle-low (between 1 and 2 million KRW)ŌĆØ for the second, ŌĆ£middle-high (between 2 and 3 million KRW)ŌĆØ for the third, and ŌĆ£high (more than 3 million KRW)ŌĆØ for the last quartile. In the employment survey, except for military services, those who answered, ŌĆ£managers, experts, and associated workersŌĆØ were deemed ŌĆ£professional jobsŌĆØ and the others ŌĆ£manual labor or unemployed.ŌĆØ

6. Statistical Analyses

We conducted weighted analyses to comprehensively understand the changes in population behavior. The chi-square test was used to investigate the association between tobacco use and smoking cessation behavior in all combinations made by CC and HTP, that is, CC only, HTP only, and CC+HTP dual users, with a P-value of <0.05, which was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were carried out using STATA ver. 16.1 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA) throughout the study.

DISCUSSION

The release of novel tobacco products has had a tremendous impact on individuals and society in the global tobacco market. Since its debut in the market in 2003, it has been reported that EC has numerous potential risks to humans at various levels. Its use was restricted after an outbreak of e-cigarette or vaping use-associated lung injury (EVALI) in 2019, defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as an acute or subacute pulmonary disorder with a mixture of respiratory symptoms and death. The pathogenesis of EVALI is unclear, but vitamin E acetate in the component of EC is considered one of the major causes of EVALI [

10].

Launched in 2014, HTP is rapidly expanding its market share. Based on Euromonitor data in 2019, the worldŌĆÖs largest market for HTPs is Japan (8.6 billion in US dollar [USD]), followed by South Korea (1.6 billion USD), Italy (1 billion USD), Russia (rapidly increasing two times in the market since 2018), and other European countries [

11]. The most popular brand of HTP is IQOS made by Phillip Morris International, sold in 66 countries as of March 2021, and is expected to expand to 100 countries by 2025. Other brands, such as Glo and Lil, made by the British American Tobacco and Korea Tobacco & Ginseng Corporation (KT&Q), respectively, account for substantial market share. The number one tobacco manufacturer in South Korea, KT&Q, introduced Lil to the domestic market in the fourth quarter of 2017, contributing to the market share of novel tobacco products [

12,

13].

It is well known that younger generations access HTPs by virtue of their ease of use and the pursuit of healthy features. Many factors, such as health, financial, physical, practical, psychological, and social factors, are related to HTP use and its relevant behavior independently and with one another [

14,

15]. Even though the majority of tobacco manufacturers insist that HTP contains less nicotine level that will make smokers less dependent on and then get healthier than any other CC user, a lot of the facts have not yet been elucidated regarding the health impact on humans.

Given that the WHO argued to explore and implement strategies to minimize net impairment of health consumption regardless of how many nicotine-containing products are consumed, tobacco harm reduction strategies seem to be effective not only for conventional smokers but also for novel product users willing to reduce their own amount of tobacco use [

16].

Several pieces of evidence contradict this argument. In contrast to the manufacturerŌĆÖs opinion, several independent researchers reported that there was a comparable level of nicotine and other additives, such as volatile materials, heavy metals, and even unknown materials, which will have an adverse effect on humans through a collection of undisclosed mechanisms [

17]. Even a small amount of tobacco use can elevate the risk of cardiovascular diseases [

18,

19]; even one-cigarette smoking can affect health. Chang et al. [

20] reported that total mortality and cardiovascular diseases cannot be reduced even if smoking amount is reduced, meaning that the novel tobacco products still pose a detrimental effect on health in a small amount. There is no doubt that it will take several decades to shed light on the long-term harmful effects of tobacco use, and in the case of HTPs, there are some studies for only a short period of time, but no long-term effects [

21].

Despite many efforts to reduce the harmful consequences of tobacco use, tobacco use and cessation practices have moved away from the existing trend after the introduction of novel tobacco products. The awkward trend has been accelerating since 2017 when HTPs were introduced in South Korea. The overall tobacco sales, sum of CCs, and novel tobacco products have not diminished since 2017, albeit with a decrease in that of CCs. Along with the fact that the number of visits to tobacco cessation clinics has declined during the same period, the novel tobacco products are considered successful in the market for tobacco manufacturers against the pre-existing endeavor for tobacco cessation. Although many countries have established regulation policies, including for novel products, the type and extent of methods vary greatly among them, and it is difficult to control the subsequent short- and long-term effects of product use. To determine what is going on tobacco use status per se by previous surveys consisting of a questionnaire related to CCs, it will be necessary to investigate the changes in the pattern over time to establish and execute tobacco control policies based on national statistics reflecting the behavior of novel tobacco product use [

5,

22].

More serious problems related to tobacco use remain among the adolescents. Adolescents are disposed of using dual products and are associated with allergic diseases with the entrance of novel tobacco products into the market [

23]. Moreover, they are vulnerable to substance abuse, such as alcohol use problems, especially in females, and proper action is needed to establish a sustainable and healthy society [

24,

25].

Among the different types of current tobacco users, the finding in

Table 1 that CC users were the most followed by any HTP and any EC users regardless of gender reflects the recent boom and steady upward trend of HTPs in South Korea, similar to the percentage of HTP use in the previous study [

26]. This is more noticeable in

Table 2, which shows each product userŌĆÖs own behavior with tobacco product use by gender, especially among female users. In females with a small proportion of current tobacco product users, the relative ratio of HTP to CC and EC use, even in a very small percentage, was by no means small, consistent with a previous study that reported a gradual increase in female HTP users, from 5.5% in 2015 to 7.5% in 2018 for adult women, and from 2.7% in 2016 to 3.8% in 2019 for adolescent women [

4].

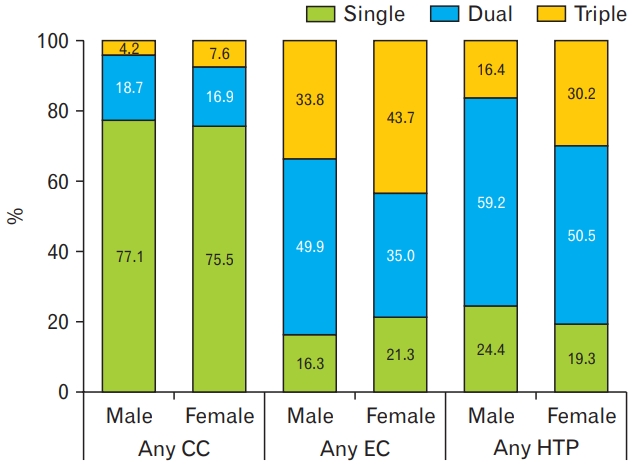

It is noteworthy that the finding that there were about 70% of concurrent CC users among any EC and HTP users (

Table 2) and more than 70% of redundant users among HTP users, as shown in

Figure 2, has a similar trend to that of Kim et al. [

3] and Tabuchi et al. [

27]; however, with slightly different proportions because they were based on online survey data. Another finding that no ŌĆ£never CC experienceŌĆØ and a substantial fraction of ŌĆ£current CC experienceŌĆØ as shown in

Table 2 suggests that all novel tobacco product users have already experienced and are currently experiencing CCs in adults. That should be noted because it shows the possibility against an existing theory, ŌĆ£Gateway theory,ŌĆØ which states that novel tobacco products could be a gateway to nicotine addiction through subsequent use and moving on to the ŌĆ£harderŌĆØ step by vulnerable users, such as adolescents [

28], as shown in a previous study with higher concurrent use of CC and EC among them [

29]. A longitudinal study of Korean adolescents is necessary to confirm this hypothesis.

Furthermore, among all combinations of CC and HTP, comprising the largest proportion of total current tobacco product users, it is remarkable that there was the lowest percentage of HTP users who have tried tobacco cessation in the past year and most recently, but different proportions, as shown in

Table 3, which is in line with previous studies [

4,

6].

Considering that the respondents could make duplicate answers to the survey on how to quit tobacco use, HTP only users had the highest percentage of direct actions, such as by themselves and visiting tobacco cessation clinics in public health centers, pharmacies, and hospitals compared to the others. The discrepancy between attempts to quit tobacco use at different periods could be explained by two factors. First, those who had strived for tobacco cessation in the past year did the same thing most recently, leading to a response at a lower rate. Second, inconsistent responses would be possible, given the decrease in different rates from quitting tobacco in the past year to most recently among the groups in

Table 3.

Given the finding of different tobacco use and cessation behaviors among daily and intermittent users of any type of tobacco products in

Table 4, it is presumed that there were different degrees of nicotine dependence among themŌĆōhigher in dual users than single users and in daily users than intermittent ones, which is similar to the study by Borland et al. [

9], except that it dealt with ECs rather than HTPs.

This study has several limitations. It is difficult to know specific behavioral changes in the tobacco product users in view of the fact that it is based on cross-sectional research in 2019. Because the study is based on a self-reporting questionnaire, there are vague expressions, for example, ŌĆ£most recently,ŌĆØ and the criteria for when is unclear. This can confuse respondents, requiring more definite questions to accurately reflect their behavior and reduce the gap; about 40% reported in the previous studyŌĆöbetween survey results and the real world [

30].

It is difficult to explain the reversal of trends in cigarettes or sticks per day for daily CC+HTP dual users; they were distributed in order from the lower category of cigarettes or sticks per day in other users but not in CC+HTP dual users. This was similar to the lower rate at the preparation stage in cessation for intermittent CC+HTP dual users than the daily ones. A blow-by-blow analysis, including the tobacco use trajectory of the users will be necessary to determine the reasons why those users have unique characteristics.

Despite these restrictions, this study has strengths. It analyzed tobacco use and cessation behavior with a sample group, representing the whole population in South Korea. Notably, this is the first study to summarize the terms total current tobacco users and non-tobacco users related to the use of CCs and novel tobacco products to reflect changes in behavior of tobacco use, with a slight modification to the existing terms, CPD and TTFC. Moreover, it is the first research to assess daily and intermittent HTP users with more detailed questionnaire items of HTPs in 2019, different ever before in South Korea. Additionally, it is the first study to suggest that existing the ŌĆ£gateway theoryŌĆØ needs to be tested for adolescents in South Korea afterwards.

In summary, the prevalence of HTP use in men and women aged Ōēź19 years in South Korea in 2019 was 8.8% and 1.5%, respectively. The proportions of single, dual, and triple users of HTPs were 23.6%, 58.0%, and 18.4%, respectively. Among single and dual users, consisting of CC and HTP, differences in the behavior of tobacco use and cessation were observed, which were similar when the users were subdivided into frequency of use. Dual users were more dependent on nicotine than single users and so were daily users than intermittent users of each product group.