|

|

- Search

| Korean J Fam Med > Epub ahead of print |

|

Abstract

Background

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has disrupted healthcare services, including chronic disease management, for vulnerable groups, such as older individuals with hypertension. This study aimed to evaluate hypertension management in South Korea’s elderly population during the pandemic using treatment consistency indices such as the continuity of care (COC), modified, modified continuity index (MMCI), and most frequent provider continuity (MFPC).

Methods

This study used the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency-COVID-19-National Health Insurance Service cohort (K-COV-N cohort) from the National Health Insurance Service between 2017 and 2021. The research included a total of 4,097,299 hypertensive patients aged 65 years or older. We defined 2018 and 2019 as the baseline period before the COVID-19 pandemic and 2020 and 2021 as the COVID-19 period and calculated the indices of medical continuity (number of visits, COC, MMCI, and MFPC) on a yearly basis.

Results

The number of visits decreased during the COVID-19 period compared to the baseline period (59.64±52.75 vs. 50.49±50.33, P<0.001). However, COC, MMCI, and MFPC were not decreased in the baseline period compared to the COVID-19 period (0.71±0.21 vs. 0.71±0.22, P<0.001; 0.97±0.05 vs. 0.96±0.05, P<0.001; 0.8±0.17 vs. 0.8±0.17, P<0.001, respectively).

Conclusion

COVID-19 had no significant impact on the continuity of care but affected the frequency of outpatient visits for older patients with hypertension. However, this study highlights the importance of addressing healthcare inequalities, especially in older patients with hypertension, during pandemics and advocates for policy changes to ensure continued care for vulnerable populations.

During the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, social distancing policies resulted in many disruptions to healthcare services, with chronic disease management being one of the most severely affected [1]. The international primary care response to the COVID-19 pandemic has prioritized urgent services for COVID-19 patients as well as counseling and delivery of COVID-19 vaccines [2]. Prioritization often results in partial or complete disruption of chronic disease management. However, restricted access to health care services usually affects the most vulnerable groups. In particular, older people may be at a higher risk of poor outcomes due to reduced or delayed healthcare services because they tend to have comorbidities associated with complications when timely treatment is not provided [3]. Additionally, social isolation can negatively affect primary care, especially in elderly patients [4].

Hypertension is one of the most common chronic diseases requiring routine management by healthcare services. Donabedian [5] reported that treatment persistence in chronic diseases such as hypertension and diabetes has a significant effect on the progress and treatment of the disease. It is especially important to manage hypertension in primary care because high blood pressure is the most important modifiable risk factor with the most significant influence on cardiovascular or cerebrovascular diseases [6]. Many studies have been conducted on mortality or complications in patients with hypertension during the COVID-19 pandemic. A meta-analysis showed that the mortality risk increases steadily in hypertensive patients who are positive for COVID-19 with underlying cardiovascular diseases, particularly hypertension, and are prone to the highest morbidity following infection [7].

However, few studies that have examined medical utilization during the COVID-19 pandemic, including 2021, when the Omicron variant began to appear, have focused on medical utilization for chronic diseases in elderly individuals. In the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic (in 2020, before vaccination began in Korea), many studies on medical utilization primarily focused on emergency admissions with urgent conditions and chronic disease management.

Increasing the continuity of care can prevent sudden deterioration of diseases in chronic patients and affect disease treatment. Enhanced treatment continuity can improve patient satisfaction and quality of life, reduce emergency department visits and hospitalizations related to complications, and improve patient outcomes [8]. There are many ways to measure treatment continuity, among which the continuity of care index (COC), modified, modified continuity index (MMCI), and most frequent provider continuity (MFPC) are the most widely used indices, which can be used to measure the concentrations of visits and treatment consistency [9].

Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate whether hypertension has been consistently managed in individuals aged 65 years or older during the COVID-19 pandemic in South Korea.

This retrospective cohort study aimed to analyze the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the continuity of care in elderly outpatients with hypertension. We used the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA)-COVID-19-National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) cohort (K-COV-N cohort) from the NHIS between 2017 and 2021. The NHIS is a mandatory universal system, and the national health insurance (NHI) claims databases are nationally representative of healthcare resource utilization for the entire Korean population. It contains information about the patients’ age, sex, type of insurance, diagnosis, treatment history, and type of hospital. This study was exempt from review by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (X-2207-768-901) as it used de-identified data provided by the NHIS according to the NHIS Personal Information Protection Guidelines.

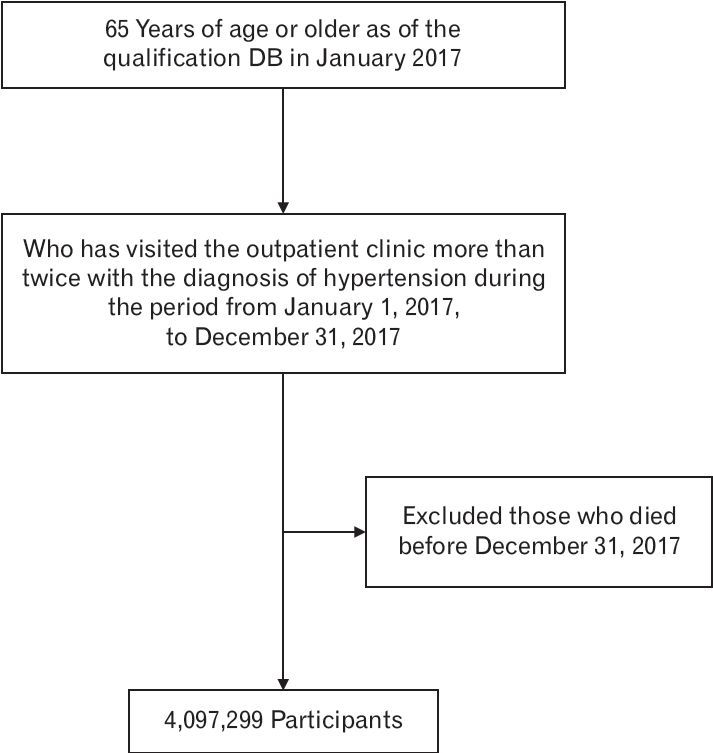

The study subjects were adults aged 65 years or older who were diagnosed with hypertension between January 1 and December 31, 2017. The diagnosis of hypertension was defined as an International Classification of Diseases (ICD) code (I10: essential hypertension; I11: hypertensive heart disease; I12: hypertensive renal disease; I13: hypertensive heart and renal disease) included in the major diagnosis or sub-diagnosis or the third to fifth priority diagnosis code and having outpatient records more than twice. If there were multiple medical records on the same date, they were considered one. Visits for diagnostic tests or medical procedures other than physician consultations were excluded. Patients who died between January and December 2017 were excluded from the study. We defined 2018 and 2019 as the baseline period before the COVID-19 pandemic and 2020 and 2021 as the COVID-19 period and calculated the indices of medical continuity on a yearly basis (Figure 1).

The number of visits to a medical institution per year is a representative variable for measuring the volume of healthcare utilization. Visits for diagnostic tests or medical procedures other than physician consultations were excluded. Medical continuity was confirmed based on the number of medical applications. Continuity of care was measured using three representative indices [9,10]: COC [11], MMCI [12], and MFPC [13].

COC represents the distribution of the frequency of outpatient visits depending on the healthcare provider [11]. The COC reflects the outpatient visit count and the utilization of medical institutions by patients. It gauges the extent to which a patient’s healthcare events are interconnected, coherent, and uninterrupted. This assessment evaluates the consistency of the care provided to patients over time and across healthcare providers. If there was a consistent distribution of the frequency of visits according to different medical institutions, the COC tended to increase with the increasing frequency of outpatient visits. This is because the calculation formula includes the squared term of the outpatient visit frequency for each healthcare provider in the numerator.

The MMCI includes the number of available healthcare providers (M) and the overall frequency of outpatient visits (N) in formula [14]. The MMCI reflects the total number of visits to medical institutions, considering the overall visit count and the diversity of medical facilities. It serves as a healthcare measure for evaluating the degree of continuity in patient care. Therefore, it consistently reflects the frequency of outpatient visits and the relevant distribution of healthcare providers other than MFPC.

The MFPC indicates the frequency of outpatient visits based on the most frequent healthcare provider in cases where the patient does not have a designated primary care physician [15]. The MFPC measures the concentration of patient visits by the most frequently accessed medical providers. It evaluates the consistency of healthcare services by identifying the provider most frequently visited by a patient and emphasizes continuity of care through the patient’s recurring interactions with a specific healthcare provider. This reflects the degree to which patient visits are concentrated at the most frequently visited medical providers.

If the frequency of visits is insufficiently frequent, it may lead to inflated calculations for MMCI and MFPC. Therefore, those who visited medical institutions less than twice per year were excluded. We also calculated whether there were differences in the annual number of days of visit and treatment persistence indices depending on the type of insurance and medical institution.

The demographic statistics of the study are summarized using frequency percentages, as appropriate. Number of visits per year, COC, MMCI, and MFPC were expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD). The continuity level was compared between baseline and COVID-19 within each insurance premium section and each type of medical institution using a t-test. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS ver. 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed P-value of <0.05.

Table 1 shows the general characteristics of the study population. A total of 2,115,018 hypertensive patients (51.62%) aged 65–74 years and older and 1,982,281 hypertensive patients (48.38%) aged 75 and older were included. Approximately two-thirds were female (59.77%, n=2,448,969), and one-third were male (40.23%, n=1,648,330). Regarding the type of health insurance premium, NHI accounted for the majority, and medical aid accounted for 7.31%. The NHI was classified into the 1st quartile (highest) to the 4th quartile (lowest) according to the health insurance premium, and 41.3% of the patients were in the 1st quartile. By region, the metropolitan area had the largest number of residents at 2,550,485 (62.25%), while the other area had 1,546,814 (37.75%). According to the type of medical institution, 97% of outpatients visited clinics at least once in 4 years (2018–2021), while 56.33%, 33.53%, and 57.19% visited hospitals, general hospitals, and tertiary hospitals, respectively. The number of visits to medical institutions during the 4 years was also the highest in clinic at 84.2 days; the number of visits to general hospitals, hospitals, and tertiary hospitals was 13.1, 8.1, and 7.1, respectively.

Table 2 shows the number of visits, COC, MMCI, and MFPC during the baseline and COVID-19 periods in South Korea. The number of visits was 30.25±27.57 (mean±SD) in 2018, 29.39±28.04 in 2019, 25.85± 26.53 in 2020, and 24.64±26.34 in 2021. However, COC was 0.73±0.23 in 2018, 0.73±0.23 in 2019, 0.73±0.23 in 2020, and 0.73±0.23 in 2021, which was similar during the baseline and COVID-19 periods. Furthermore, MMCI was 0.95±0.07 in 2018, 0.95±0.07 in 2019, 0.95±0.07 in 2020, and 0.94±0.07 in 2021; MFPC was 0.82±0.18 in 2018, 0.81±0.18 in 2019, 0.82±0.18 in 2020, and 0.81±0.18 in 2021. These two indices were also similar during the baseline and COVID-19 periods.

In Table 3, we analyze whether the number of outpatient visits varies depending on the type of medical institution and whether there is a difference in the number of outpatient visits due to the COVID-19 epidemic at each NHI income level. Compared to the baseline period, the total number of visit significantly decreased from 59.64±52.75 to 50.49±50.33 days after COVID-19 (P<0.001). In terms of health insurance premium level and type, the number of visits in all groups during the COVID-19 period decreased compared to the baseline period and were statistically significant. In NHI, it decreased by approximately 8–10 days for each group regardless of income quartile; in medical aid, it decreased by 14 days from 69.94±61.29 to 55.88±58.87 days (P<0.001). Additionally, the number of visits decreased according to the medical institution after COVID-19 compared to the baseline. The number of visits decreased during the baseline from 70.61±55.39, 70.34±56.88, 73.82±57.18, and 63.52±52.85 to 62.32±53.89, 61.68±54.60, 65.29±54.40, and 56.35±50.10 during COVID-19, respectively, for tertiary hospitals, general hospitals, hospitals, and clinics.

The total continuity of care indices (COC, MMCI, and MFPC) did not exhibit a statistically significant decrease during the baseline period compared to the COVID-19 period, as indicated by the data in Table 4. All continuity of care indices (COC, MMCI, and MFPC) for all insurance groups (except medical aid) and medical institution types did not decrease during COVID-19 compared to the baseline period, and this difference was statistically significant (P<0.0001).

Nevertheless, as indicated by the data in Table 4, the total continuity of care indices (COC, MMCI, and MFPC) demonstrated a statistically significant decline during the COVID-19 period compared to the baseline period (P<0.0001); nonetheless, attributing this to a meaningful difference is intricate. All continuity of care indices (COC, MMCI, MFPC) exhibited no significant variation during the COVID-19 period when compared with the baseline period, which was either negligible or below 0.01 across all insurance groups and healthcare institution types.

In this large cohort study, we found that the number of visits to medical institutions by outpatients decreased after the COVID-19 pandemic among the hypertensive patients aged ≥65 years. However, the continuity of care measured by indices such as COC, MMCI, and MFPC was maintained during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with before the pandemic. Our findings suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic did not prevent elderly outpatients with hypertension from accessing essential medical services in South Korea.

Unlike previous studies that showed that the use of essential medical services decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic owing to the deterioration of medical institutions in many countries [16], our study revealed that medical continuity was maintained during COVID-19. In a meta-analysis of cardiovascular disease management, hospitalization, procedures, and outpatient treatment of patients with cardiovascular disease decreased during the pandemic, while cardiovascular disease mortality in hospitals and communities increased [17]. Twenty percent of the oldest multidisciplinary patients in the Netherlands and Hong Kong missed medical appointments for chronic disease care since the beginning of the pandemic. Older patients have cited fears of coronavirus infections as a reason for delaying healthcare-seeking behaviors [18]. In the United States, telemedicine was strengthened during the COVID-19 pandemic; however, 40.9% of those aged 18 years or older delayed or avoided medical care due to COVID-19 [19].

In South Korea, as indicated in the following section, it is evident that the management of chronic diseases has been relatively well conducted during the COVID-19 period. During the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, research on the medical utilization of the elderly revealed a decrease in hospital visits due to acute upper respiratory infectious diseases. Nevertheless, medical utilization for chronic conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and cancer remains unaffected [20]. Similarly, in a study focusing on adults aged 30 years or older, it was observed that the management indicators of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and hypercholesterolemia did not show significant deterioration [21]. Furthermore, another study investigating the COC and MFPC of hypertensive patients between 2019 and 2020 found that COVID-19 protocols did not disrupt the COC of hypertensive patients, although there was an impact on the frequency of outpatient visits. Interestingly, medical utilization remained uninterrupted with or without telemedicine, which is consistent with the findings of our study [22].

Since the beginning of the pandemic in Korea, most hospitals, governments, and academic societies have cooperated closely, and most private hospitals have been able to maintain their continuity of care [23]. The use of telemedicine has increased with the increase in the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in Korea [24], and telemedicine could prevent contact with the infectious virus while maintaining the continuity of patient care [25]. The public healthcare system in Korea used testing and tracking strategies that were appropriately mixed with social distancing policies [26], and the government, health workers, and medical institutions showed a successful initial response to COVID-19 compared to other countries [27]. Additionally, more than 80% of Koreans have completed the COVID-19 vaccination by January 2022, and the vaccination rate is higher than that in other countries [28]. In particular, vaccination was provided preferentially to elderly individuals aged 65 years or older who were at high risk or had underlying diseases. Furthermore, many primary clinics in Korea provide physical places for COVID-19 vaccination, allowing patients with chronic diseases to be vaccinated at any clinic [29]. It is known that vaccination rates are higher in patients with chronic disease [29], In South Korea, antihypertensive drugs could be prescribed on the day of vaccination, or drugs such as remdesivir could be prescribed for COVID-19 infection treatment. These characteristics are assumed to have contributed to maintaining medical continuity in elderly patients with hypertension in Korea.

This study has several limitations. The use of data from the Korea NHI Claims database precludes the incorporation of clinical information such as income level, education, residential area, social determinants of health, health behaviors, physical measurements, and patient preferences. The characteristics of the claims data limited the analysis of the clinical characteristics of elderly patients with hypertension and their medical utilization. Further, this study could not determine how medical utilization patterns differed depending on the accessibility of telemedicine services. However, using telemedicine is challenging for the elderly patients to use telemedicine [30]. Even during the COVID-19 pandemic in South Korea, when most telemedicine is conducted through telephone consultations, younger patients utilize telemedicine more frequently than older patients [24]. This is believed to be due to the difficulties encountered by older patients in activities such as buying medications and the payment process after medical consultation. As our study was conducted in adults aged 65 years or older, the use of telemedicine may not have had a significant impact on healthcare utilization. Moreover, as the study focused only on hypertensive outpatient medical utilization, a patient who was admitted during the COVID-19 pandemic due to complications of hypertension, such as cardiovascular disease or stroke, may have been classified as not having received any medical care at all. Additionally, as hypertension typically lacks noticeable symptoms, prompt recognition of issues becomes challenging, even with slight delays in management. Therefore, follow-up studies are necessary to ensure that complications due to high blood pressure do not increase in the future. In this study, we defined patients with hypertension using ICD-10 codes, which may have led to an overestimation of hypertension cases. Nevertheless, we believe that this would have had a minimal impact on the pre- and COVID-19 periods comparison. Finally, this study did not analyze medical accessibility, such as insurance premiums or regions. Thus, the study does not reflect health inequality in medical utilization.

Despite these limitations, our study has several strengths. First, the NHI claims dataset is a representative large dataset that covers all citizens in Korea. Our study analyzed the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic and the following 2 years, encompassing the Omicron variation and the period after social distancing measures were lifted. Second, our findings are the first to examine the impact of COVID-19 on COC, MMCI, and MFPC during the 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic in South Korea. Nonetheless, long-term research is necessary to explore how medical utilization varies depending on the socioeconomic level and clinical characteristics of patients with high blood pressure, as well as inpatients with hypertension complications and other chronic diseases, including during COVID endemic periods.

In conclusion, this study suggests that COVID-19 did not significantly affect older hypertensive patients’ COC, MMCI, and MFPC but impacted the frequency of their outpatient visits. Moreover, when health insurance premiums and medical institutions were considered, the COC was the same according to medical institutions but not according to insurance premiums. It is essential to maintain agility and adaptability in response to the emergence of various infectious diseases, including COVID-19. Additionally, the persistence of care for patients with hypertension and other vulnerable populations should remain a priority, even in difficult times, to mitigate the impact of the pandemic on public health.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was conducted as part of a public-private joint research on COVID-19 co-hosted by the KDCA and NHIS. This study uses the KDCA and NHIS databases for policy and academic research. The research number for this study was KDCA-NHIS-2022-1-528.

Table 1.

Description of study population

Table 2.

Number of visits and continuity of care during baseline period versus COVID-19 period

Table 3.

Number of visits according to insurance and hospital type

Table 4.

Continuity of care indices according to insurance and hospital type

REFERENCES

1. Wright A, Salazar A, Mirica M, Volk LA, Schiff GD. The invisible epidemic: neglected chronic disease management during COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med 2020;35:2816-7.

2. Matenge S, Sturgiss E, Desborough J, Hall Dykgraaf S, Dut G, Kidd M. Ensuring the continuation of routine primary care during the COVID-19 pandemic: a review of the international literature. Fam Pract 2022;39:747-61.

3. Cohen MA, Tavares J. Who are the most at-risk older adults in the COVID-19 era?: it’s not just those in nursing homes. J Aging Soc Policy 2020;32:380-6.

4. Cayenne NA, Jacobsohn GC, Jones CM, DuGoff EH, Cochran AL, Caprio TV, et al. Association between social isolation and outpatient follow-up in older adults following emergency department discharge. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2021;93:104298.

5. Donabedian A. Explorations in quality assessment and monitoring: the definition of quality and approaches to its assessment. Ann Arbor (MI): Health Administration Press; 1980.

6. Yusuf S, Joseph P, Rangarajan S, Islam S, Mente A, Hystad P, et al. Modifiable risk factors, cardiovascular disease, and mortality in 155 722 individuals from 21 high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries (PURE): a prospective cohort study. Lancet 2020;395:795-808.

7. Driggin E, Madhavan MV, Bikdeli B, Chuich T, Laracy J, Biondi-Zoccai G, et al. Cardiovascular considerations for patients, health care workers, and health systems during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;75:2352-71.

8. Chan KS, Wan EY, Chin WY, Cheng WH, Ho MK, Yu EY, et al. Effects of continuity of care on health outcomes among patients with diabetes mellitus and/or hypertension: a systematic review. BMC Fam Pract 2021;22:145.

10. Dreiher J, Comaneshter DS, Rosenbluth Y, Battat E, Bitterman H, Cohen AD. The association between continuity of care in the community and health outcomes: a population-based study. Isr J Health Policy Res 2012;1:21.

12. Gill JM, Mainous AG 3rd. The role of provider continuity in preventing hospitalizations. Arch Fam Med 1998;7:352-7.

13. Given CW, Branson M, Zemach R. Evaluation and application of continuity measures in primary care settings. J Community Health 1985;10:22-41.

14. Magill MK, Senf J. A new method for measuring continuity of care in family practice residencies. J Fam Pract 1987;24:165-8.

15. Breslau N, Reeb KG. Continuity of care in a university-based practice. J Med Educ 1975;50:965-9.

16. Chudasama YV, Gillies CL, Zaccardi F, Coles B, Davies MJ, Seidu S, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on routine care for chronic diseases: a global survey of views from healthcare professionals. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2020;14:965-7.

17. Nadarajah R, Wu J, Hurdus B, Asma S, Bhatt DL, Biondi-Zoccai G, et al. The collateral damage of COVID-19 to cardiovascular services: a meta-analysis. Eur Heart J 2022;43:3164-78.

18. Nab M, van Vehmendahl R, Somers I, Schoon Y, Hesselink G. Delayed emergency healthcare seeking behaviour by Dutch emergency department visitors during the first COVID-19 wave: a mixed methods retrospective observational study. BMC Emerg Med 2021;21:56.

19. Czeisler ME, Marynak K, Clarke KE, Salah Z, Shakya I, Thierry JM, et al. Delay or avoidance of medical care because of COVID-19-related concerns: United States, June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1250-7.

20. Park K, Byeon J, Yang Y, Cho H. Healthcare utilisation for elderly people at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in South Korea. BMC Geriatr 2022;22:395.

21. Kim Y, Park S, Oh K, Choi H, Jeong EK. Changes in the management of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and hypercholesterolemia in Korean adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: data from the 2010-2020 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Epidemiol Health 2023;45:e2023014.

22. Lee SY, Chun SY, Park H. The impact of COVID-19 protocols on the continuity of care for patients with hypertension. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19:1735.

23. Lee S, Lim AR, Kim MJ, Choi YJ, Kim JW, Park KH, et al. Innovative countermeasures can maintain cancer care continuity during the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic in Korea. Eur J Cancer 2020;136:69-75.

24. Kim HS, Kim B, Lee SG, Jang SY, Kim TH. COVID-19 case surge and telemedicine utilization in a tertiary hospital in Korea. Telemed J E Health 2022;28:666-74.

25. Eberly LA, Khatana SA, Nathan AS, Snider C, Julien HM, Deleener ME, et al. Telemedicine outpatient cardiovascular care during the COVID-19 pandemic: bridging or opening the digital divide? Circulation 2020;142:510-2.

26. Ministry of Health and Welfare; Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention. All about Korea’s response to COVID-19 [Internet]. Seoul: Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Task Force for Tackling COVID-19 [cited 2023 Sep 3]. Available from: https://ncov.kdca.go.kr/SynapDocViewServer/viewer/doc.html?key=5fd0f5cde03c4ec7b9bb54d07fb26c1b&convType=img&convLocale=en_US&contextPath=/SynapDocViewServer

27. Oh J, Lee JK, Schwarz D, Ratcliffe HL, Markuns JF, Hirschhorn LR. National response to COVID-19 in the Republic of Korea and lessons learned for other countries. Health Syst Reform 2020;6:e1753464.

28. Jung J. Preparing for the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) vaccination: evidence, plans, and implications. J Korean Med Sci 2021;36:e59.