INTRODUCTION

Over the past two decades, several studies have highlighted a considerable increase in the risk of vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) using metformin [1-5]. Many risk factors have been identified, and notably, a neurological impact has been demonstrated by numerous authors [2,6-8]. Despite these data, it was only in 2017 that the American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommended considering periodic vitamin B12 testing in metformin-treated patients [9]. No clear guidelines have been published regarding screening, diagnosing, and managing these deficiencies. The best cutoff value for diagnosing vitamin B12 deficiency and the usefulness of vitamin B12 biomarkers, particularly in asymptomatic patients, remain controversial.

The worldwide prevalence of T2D is steadily increasing, and the International Diabetes Federation predicts that the prevalence of diabetes, 10.5% in 2021, will rise to 11.3% by 2030 [10]. Metformin is the firstline glucose-lowering drug recommended for treating and preventing T2D [11]. This medication is widely prescribed, either alone or in combination with other antidiabetic agents, because of its effectiveness, low cost, beneficial effects on weight, and ability to reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [12,13].

Considering the absence of a consensus on diagnostic methods, screening criteria, and treatment for vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with T2D receiving metformin, this narrative review had the following aims: (1) Discuss the diagnostic criteria for vitamin B12 deficiency and the utility of vitamin B12 biomarkers. (2) Suggest a practical diagnostic and therapeutic strategy for addressing vitamin B12 deficiency in individuals with T2D receiving metformin treatment.

Additionally, we examined pertinent topics within this field, including clinical evidence demonstrating an increased risk of vitamin B12 deficiency, potential mechanisms elucidating this elevated risk, and the risk factors and consequences of vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with T2D receiving metformin therapy.

ASSESSMENT OF VITAMIN B12 STATUS: USEFULNESS AND LIMITATIONS OF BIOMARKERS

The total serum vitamin B12 (cobalamin) level is frequently insufficient as a standalone marker to accurately evaluate vitamin B12 status. This is because serum vitamin B12 quantifies biologically active and inactive forms, which serve to establish liver stores.

Holotranscobalamin is the biologically active form bound to transcobalamin II, accounting for 20% to 25% of the total measured vitamin B12. The inactive form, bound to transcobalamins I and III, is holohaptocorrine, represents 75%–80% of the total measured vitamin B12 [14,15]. Thus, serum vitamin B12 levels can be falsely normal in cases of liver damage, alcoholism, or myeloproliferative syndrome and falsely decreased in other situations, such as pregnancy. Measuring holotranscobalamin, the active form of vitamin B12, offers better sensitivity and specificity; however, it is not widely available and requires validation in patients with hepatic, renal, and hematological comorbidities. Furthermore, measuring circulating vitamin B12 levels does not reflect cellular function. Normal or elevated vitamin B12 levels can be observed in individuals with functional abnormalities of vitamin B12. Therefore, some scientific societies have recommended measuring cellular vitamin B12 biomarkers, such as homocysteine and methylmalonic acid (MMA), to uncover intracellular vitamin B12 deficiency [14-16]. Vitamin B12 acts as a cofactor for the enzymes involved in the metabolism of homocysteine and MMA. Elevated levels of these biomarkers would, therefore, reflect tissue-level vitamin B12 deficiency [15-17].

Folate deficiency is also associated with increased levels of these biomarkers, especially homocysteine. Therefore, it is important to first rule out folate deficiency in patients with elevated biomarker levels. MMA levels should be interpreted with caution in individuals with renal failure because this situation is associated with elevated levels of this biomarker [14].

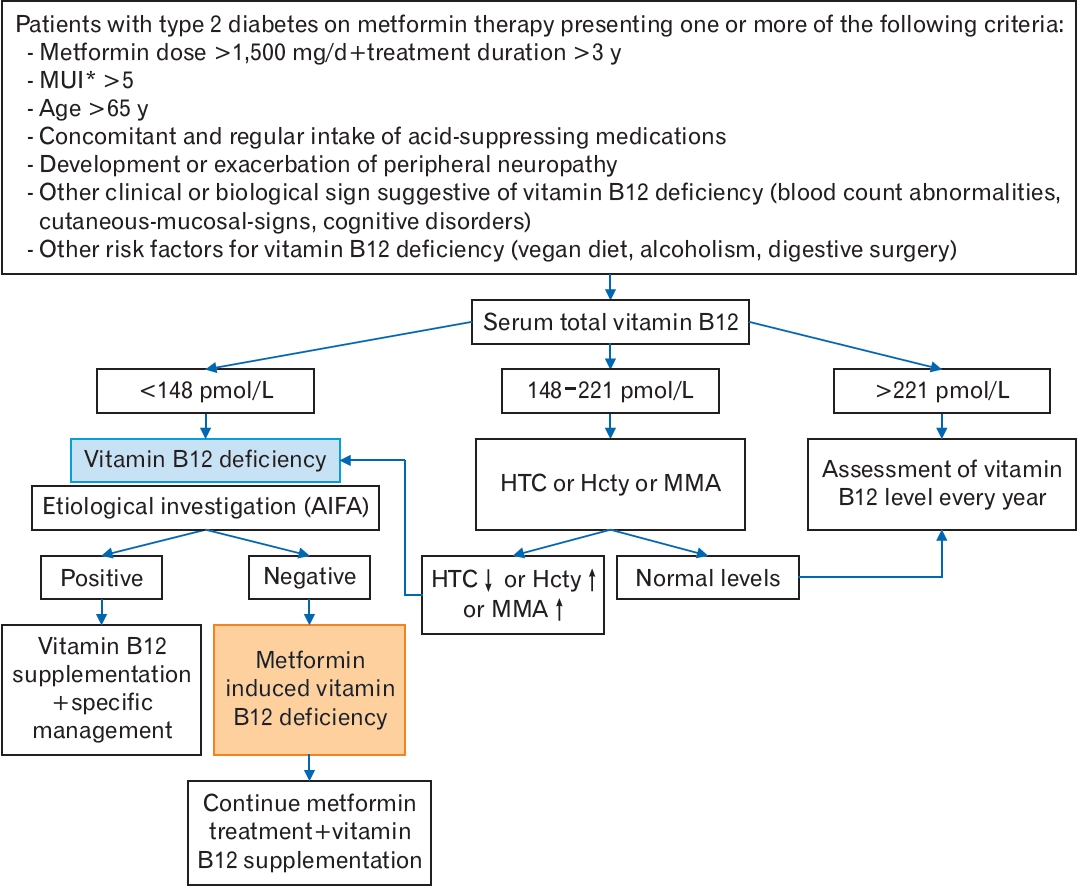

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR VITAMIN B12 DEFICIENCY

In situations where vitamin B12 levels are not markedly low, and there are no apparent symptoms, such as macrocytic anemia, it remains difficult to diagnose vitamin B12 deficiency based solely on the measurement of vitamin B12. A level below 148 pmol/L (200 pg/mL) is the cutoff value usually applied to define low vitamin B12 status [14-18]. A level below this cutoff, coupled with clinical signs of vitamin B12 deficiency, establishes a diagnosis of vitamin B12 deficiency [14]. A level ranging from 148 to 221 pmol/L (range, 200 to 300 pg/mL) is considered “borderline,” and the measurement of one of the vitamin B12 biomarkers, such as holotranscobalamin, homocysteine, or MMA, has been suggested [14-17]. In the absence of suggestive symptoms, the British Society of Hematology suggests a lower cutoff, less than 110 pmol/L, to consider the diagnosis of vitamin B12 deficiency. If the vitamin B12 level is between 110 pmol/L and 148 pmol/L without suggestive symptoms, the measurement of anti-intrinsic factor antibodies is recommended [14]. If these antibodies are negative, the assessment of one of the vitamin B12 biomarkers (holotranscobalamin, MMA, or homocysteine) is required to confirm biochemical deficiency [14].

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR VITAMIN B12 DEFICIENCY USED IN STUDIES ASSESSING THE VITAMIN B12 STATUS IN PATIENTS WITH T2D ON METFORMIN THERAPY

Despite the diagnostic specificities of vitamin B12 deficiency and the necessity to measure biomarkers without suggestive symptoms, most studies assessing the risk of vitamin B12 deficiency in metformintreated patients rely solely on total vitamin B12 levels to confirm the diagnosis. The cutoff value was usually 150 pmol/L (203 pg/mL). Numerous studies have examined homocysteine levels to determine whether vitamin B12 deficiency occurs at the tissue level [2,3,19-21]. Some studies have concurrently assessed folate and vitamin B12 levels [21-23]. Holotranscobalamin, the biologically active form of vitamin B12, and MMA have been jointly analyzed with respect to vitamin B12 levels in some studies [20-22,24-26]. However, the size of the study populations in the latter studies was smaller than in those relying solely on vitamin B12 levels to define vitamin B12 deficiency. Only the study by Davis et al. [24], which considered holotranscobalamin levels, included a sample of more than 1,000 patients. Numerous studies have additionally examined the prevalence of a “borderline” vitamin B12 level, often defined within the range of 148 to 221 pmol/L (range, 200 to 300 pg/mL) [2-5,19,27].

INCREASED PREVALENCE OF VITAMIN B12 DEFICIENCY IN PATIENTS WITH T2D ON METFORMIN THERAPY: CLINICAL EVIDENCE

Determining the prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with T2D on metformin therapy is difficult because of the different cutoff values used to define vitamin B12 deficiency, the use or lack of biomarkers in diagnostic criteria, and the heterogeneity of studied populations concerning age, geographical origin, dietary patterns, and duration of metformin use. This prevalence ranged from 6% to 50% in the literature [17,28-31].

Table 1 summarizes the findings of the main studies that investigated vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with T2D using metformin over the past decade. We analyzed only comparative studies that included a control group and involved more than 300 patients. Most of these studies reported a higher frequency of vitamin B12 deficiency in the metformin-treated group, irrespective of the definition adopted. The study published by Aroda et al. [2] in 2016 was the main interventional study on which the ADA has relied since 2017 to recommend regular monitoring of vitamin B12 levels in individuals treated with metformin, particularly in the presence of neuropathy or anemia [9]. In this study, the authors found a higher frequency of vitamin B12 deficiency (≤203 pg/mL) in the “metformin” group compared with the “placebo” group after 5 years of follow-up. Moreover, nearly half of patients taking metformin with low or borderline vitamin B12 levels exhibited elevated homocysteine levels, suggesting a true tissue deficiency in vitamin B12 [2].

In addition to the cohort studies, four meta-analyses confirmed a higher frequency of vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with T2D taking metformin [28-31]. The likelihood of experiencing a deficiency in these patients was significantly increased, with a 2.45-fold risk according to a meta-analysis conducted by Niafar et al. [29] and a 2.09-fold risk reported in a meta-analysis by Yang et al. [30]

MECHANISMS OF VITAMIN B12 DEFICIENCY IN PATIENTS TREATED WITH METFORMIN

The underlying mechanisms implicated in reduced vitamin B12 levels secondary to metformin use remain unclear. Several mechanisms have been suggested [5,17,33,34]: (1) reduced intrinsic factor secretion, (2) decreased vitamin B12 release from protein complexes, (3) microbial overgrowth due to slowed intestinal transit, and (4) decreased vitamin B12-intrinsic factor complex receptors.

Presently, the most recognized mechanism involves disrupted transmembrane absorption of the intrinsic factor-vitamin B12 complex. Metformin blocks calcium channels necessary for vitamin B12 absorption at the ileal level. Thus, in the study by Bauman et al. [35], a decreased holotranscobalamin II (the active complex of vitamin B12) level was observed after 4 months of metformin treatment. After introducing 1.2 g per day of calcium supplementation for 3 months, a significant increase in the holotranscobalamin II levels was observed. Regardless of the mechanism involved, an etiological investigation of vitamin B12 deficiency is necessary before attributing it to metformin [14].

RISK FACTORS FOR VITAMIN B12 DEFICIENCY IN PATIENTS WITH T2D ON METFORMIN THERAPY

1. Metformin Treatment Duration

Numerous studies have highlighted a positive correlation between the duration of metformin treatment and the risk of vitamin B12 deficiency. In the study by Ko et al. [23], the risk of developing vitamin B12 deficiency was significantly correlated with the duration of metformin intake, with a ninefold increased risk beyond 10 years and a 4.6-fold increased risk for a treatment duration between 4 years and 10 years. In a meta-analysis by Yang et al. [30], the risk of developing vitamin B12 deficiency increased 2.9 times after 3 years of treatment. Below this duration, no significant difference was observed in the risk of vitamin B12 deficiency. In a retrospective cohort study by Martin et al. [31], the mean duration between the initiation of metformin treatment and the onset of vitamin B12 deficiency was 5.3 years. Finally, in a recent cohort study conducted by Hurley-Kim et al. [5], metformin was associated with a significantly increased risk of vitamin B12 deficiency starting in the fourth year of treatment. Interestingly, vitamin B12 deficiency resulting from insufficient alimentary intake typically takes approximately 2 to 5 years to develop, considering the important liver stores [36]. This may explain the delay between the initiation of metformin treatment and the onset of vitamin B12 deficiency.

2. Metformin Dose

In line with the duration of metformin treatment, multiple studies and meta-analyses have consistently demonstrated a positive correlation between the daily dosage of metformin and the risk of vitamin B12 deficiency. In the meta-analysis by Yang et al. [30], a daily metformin dosage exceeding 2,000 mg was associated with a more pronounced decrease in vitamin B12 levels. In the study by Alharbi et al. [37], the risk of vitamin B12 deficiency was multiplied by 21.6 in patients taking more than 2,000 mg/d of metformin. According to a case-control study conducted in Hong Kong, each 1 g/d metformin dose increment conferred a 2.88 increased risk of developing vitamin B12 deficiency [38]. More recently, in 2020, Shivaprasad et al. [4] defined a new parameter to quantify metformin exposure by combining daily dose and duration of metformin treatment. This parameter, referred to as the “Metformin Usage Index” (MUI), is determined by the formula: (daily metformin dose in milligrams×duration of metformin intake in years)/1,000. The risk of developing a vitamin B12 deficiency significantly increased when the MUI exceeded 5, with odds ratios of 6.74, 5.12, and 3.56 for MUI values exceeding 15, between 10 and 15, and between 5 and 10, respectively. Hence, the MUI can be a reliable tool for identifying individuals with an elevated risk of vitamin B12 deficiency among patients with T2D receiving metformin treatment. Finally, in 2023, Wee et al. [39] showed that vitamin B12 deficiency was present in one out of three patients receiving 1,500 mg/d of metformin. This prevalence rose to two out of three patients taking the maximum metformin dose of 3,000 mg/d.

3. Other Risk Factors

Several studies have demonstrated an increased risk of vitamin B12 deficiency among older patients using metformin [17,24,31,40,41]. Nervo et al. [40] observed a negative correlation between age and vitamin B12 levels. Notably, advanced age is a risk factor for vitamin B12 deficiency, regardless of metformin intake [42,43]. Vitamin B12 stores are depleted more rapidly in older individuals, making them more susceptible to vitamin B12 deficiency, even after a brief period of metformin usage [43]. Leung et al. [41] provided evidence of a significant decrease in total vitamin B12 and haptocorrin levels after only 3 months of metformin use in older adults.

The literature further indicates that the simultaneous intake of acidsuppressing medications (such as proton pump inhibitors [PPIs] and histamine 2 receptor antagonists [H2RAs]) with metformin increases the risk of vitamin B12 deficiency in individuals with T2D [44-48]. PPIs block the H+/K+ ATPase pump within parietal cells, consequently diminishing the transportation of H+ ions into the gastric lumen. H2RAs impede the interaction between histamine and gastric parietal cells, whose role is to stimulate the H+/K+ ATPase pump [45]. These two mechanisms reduce gastric acidity, potentially decreasing vitamin B12 levels. This reduction may occur through the decreased release of protein-bound vitamin B12 or by creating an environment with elevated pH that fosters intestinal bacterial overgrowth, subsequently diminishing vitamin B12 absorption [45,49]. In the meta-analysis conducted by Jung et al. [49], which included 4,254 patients using PPIs or H2RAs and 19,228 controls, a significant association was found between the chronic use of acid-suppressing medications (>2 years) and vitamin B12 deficiency (odds ratio, 1.83; P<0.001).

Metformin is associated with digestive disorders in 10% to 20% of cases [50], and nearly 40% of individuals with diabetes experience symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease [47,50]. This implies that a significant proportion of patients with diabetes who regularly use metformin take acid-suppressing medications, potentially increasing the risk of developing a vitamin B12 deficiency [17,50].

A significant correlation has been observed among diabetes duration, diabetes control, and vitamin B12 deficiency in some studies. Thus, in studies by Khan et al. [51] and Pfilpsen et al. [52], the risk of vitamin B12 deficiency increased with the duration of diabetes. However, the duration of metformin intake was not adjusted in these two studies. Similarly, Ahmed et al. [53] and Yazidi et al. [19] reported that better-controlled diabetes and lower hemoglobin A1c levels were associated with a higher frequency of vitamin B12 deficiency. This association was explained by better adherence to metformin in patients with well-controlled disease.

COMPLICATIONS ASSOCIATED WITH VITAMIN B12 DEFICIENCY IN PATIENTS WITH T2D ON METFORMIN THERAPY

1. Vitamin B12 Deficiency and Diabetic Neuropathy Risk in Patients with T2D on Metformin Therapy

Vitamin B12 is essential in axonal myelination by producing methionine in the central and peripheral nervous systems [54]. Several large studies and meta-analyses have highlighted an association between vitamin B12 status in patients with T2D and metformin treatment and the presence or exacerbation of peripheral diabetic neuropathy [2,3,6-8,26,55-58]. In the meta-analysis by Wang et al. [59], vitamin B12 levels were significantly lower in patients with T2D and peripheral neuropathy than in those without peripheral neuropathy. However, this metaanalysis did not consider the potential link with metformin use. Singh et al. [55] observed a negative correlation between vitamin B12 levels and the Toronto Clinical Scoring System score used for diagnosing peripheral neuropathy. In a recent cohort study, the risk of hospitalization for painful peripheral neuropathy was found to be 1.8 times higher in patients treated with metformin [8]. This risk was 1.5 times higher in patients receiving a daily metformin dose between 1 g and 2 g and 4.3 times higher in patients receiving daily metformin doses exceeding 2 g. Interestingly, in that study, patients who received vitamin B12 and metformin did not show an increased risk of hospitalization for painful peripheral neuropathy [8]. However, in the recent cohort study by Davis et al. [24], no association was observed between vitamin B12 deficiency and the frequency of peripheral diabetic neuropathy. Notably, a very low cutoff value (<80 pmol/L) was used in this study to define vitamin B12 deficiency [8]. Furthermore, according to a randomized trial conducted in a population of patients with T2D receiving metformin for at least 4 years and experiencing diabetic neuropathy, administration of 1 mg oral methylcobalamin for 1 year was associated with a significant improvement in neurophysiological parameters and scores assessing neuropathic pain and quality of life [58].

2. Vitamin B12 Deficiency and the Risk of Anemia in Patients with T2D on Metformin Therapy

The MASTERMIND study, published in 2020, analyzed two randomized trials (ADOPT [A Diabetes Outcome Progression Trial] and UKPDS [UK Prospective Diabetes Study]) and an observational cohort study (GoDARTS [Genetics of Diabetes Audit and Research in Tayside Scotland]) to assess the risk of anemia in patients with diabetes treated with metformin [60]. This study revealed a higher risk of anemia in patients with T2D on metformin treatment than in those on a diet or another antihyperglycemic agent (sulfonylurea or insulin). The data analysis from the GoDARTS cohort revealed that a daily intake of 1 g/d of metformin was associated with a 2% increase in the annual risk of anemia. Nevertheless, its association with B12 vitamin status has not been investigated [60]. Aroda et al. [2] revealed that anemia was higher in the metformin-treated group. It increased from 9.8% to 14.3% between years 1 and 5 of treatment and reached 21% in year 13. However, the risk of anemia did not correlate with the vitamin B12 status of patients, suggesting an alternative mechanism responsible for anemia in individuals with T2D receiving metformin therapy [2]. Similarly, Davis et al. [24] reported an increased risk of anemia in patients with T2D treated with metformin. This risk increased with the treatment dose but was not correlated with the vitamin B12 status of the patients. Moreover, the mean corpuscular volume was similar in patients treated with and without metformin [24].

These data suggest that the increased risk of anemia observed in patients with T2D treated with metformin cannot be explained by vitamin B12 deficiency.

3. Other Complications Associated with Vitamin B12 Deficiency in Patients with T2D on Metformin Therapy

Besides neuropathy and anemia, a limited number of studies have explored the potential link between vitamin B12 deficiency and other complications in patients with T2D on metformin therapy. Some studies have shown an increased risk of depression and cognitive disorders in individuals with T2D taking metformin and vitamin B12 deficiency [61,62].

The link between diabetic retinopathy and lower vitamin B12 levels has been highlighted in studies by Satyanarayana et al. [63] and Fotiou et al. [64]

Vitamin B12 deficiency is associated with increased homocysteine levels. This marker is associated in several studies with an increased risk of coronary insufficiency, ischemic stroke, and peripheral arterial occlusive disease [65-67]. Therefore, one might assume that vitamin B12 deficiency, through elevated homocysteine levels, is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. However, the relationship between cardiovascular outcomes and vitamin B12 levels in individuals with T2D treated with metformin remains unclear. Horrany et al. [68] found an association between vitamin B12 deficiency and the risk of stroke. In a cohort study involving 8,067 patients with T2D who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, low and high serum vitamin B12 levels were associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular disease mortality [69]. In a recent cohort study, no relationship was observed between serum vitamin B12 levels and overall or cardiac mortality in individuals with T2D, irrespective of metformin use [70]. However, high MMA levels were significantly associated with an increased risk of all-cause and cardiac mortality. The authors concluded that decreased sensitivity to vitamin B12, as indicated by high MMA levels, was associated with increased cardiac and overall mortality [70].

A PRACTICAL DIAGNOSTIC AND THERAPEUTIC APPROACH FOR VITAMIN B12 DEFICIENCY IN PATIENTS WITH T2D ON METFORMIN THERAPY

1. Screening Strategy for Vitamin B12 Deficiency in Patients with T2D on Metformin Therapy

Although the higher prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with T2D receiving metformin therapy is well established, there are no specific guidelines regarding screening modalities for vitamin B12 deficiency in this population. The British Society of Hematology stated in its 2014 guidelines that no recommendation could be made regarding the optimal frequency of monitoring serum vitamin B12 levels in patients with T2D treated with metformin. However, it is recommended that serum vitamin B12 levels be measured in patients with high clinical suspicion of deficiency [14]. Since 2017, the ADA has recommended periodic vitamin B12 testing for individuals treated with metformin, especially in the presence of peripheral neuropathy or anemia [9]. Although updated annually, this recommendation was not detailed until 2024 [11]. In routine practice, screening for vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with T2D on metformin therapy remains suboptimal, as indicated by a recent observational study [31].

Furthermore, whether vitamin B12 biomarkers should be tested in the presence of “borderline” vitamin B12 levels when no suggestive symptoms of deficiency are present in patients taking metformin remains unclear. Finally, scientific societies do not express their positions regarding the population that should be targeted for screening. It is unclear whether screening should follow a systematic approach or selectively focus on patients with risk factors or symptoms suggestive of vitamin B12 deficiency.

In June 2022, the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) considered vitamin B12 deficiency a common side effect of metformin treatment. They advised annual monitoring of serum vitamin B12 levels in patients treated with metformin, especially those receiving high doses and those who received treatment for an extended period [71,72].

Based on recent evidence, we propose an algorithm illustrating a screening and diagnostic strategy for vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with T2D on metformin therapy (Figure 1).

2. Management of Vitamin B12 Deficiency in Patients with T2D on Metformin Therapy

Specific guidelines for treating vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with T2D receiving metformin therapy are lacking. Although most experts agree on the importance of not discontinuing metformin because of its critical role in T2D management, it is essential to supplement vitamin B12 when a deficiency is identified, even without suggestive symptoms. Supplementation is essential to prevent complications associated with vitamin B12 deficiency, particularly neurological and hematological complications. However, there are currently no explicit guidelines outlining optimal supplementation approaches. Many questions regarding vitamin B12 form, dosage, administration route, and duration of treatment require clarification.

Although malabsorption is a plausible mechanism for the vitamin B12 deficiency associated with metformin treatment, normalization of vitamin B12 levels has been observed even after oral administration [57]. Bhise et al. [73] demonstrated that a 6-month supplementation with vitamin B12 improved the symptoms of diabetic neuropathy, regardless of the mode of administration (intramuscular or oral). Another emerging administration route is the sublingual route, which avoids absorption issues in the gastrointestinal tract and bypasses the first hepatic pass. Parry-Strong et al. [74] compared the effectiveness of the sublingual route with that of the intramuscular route. They demonstrated the superiority of the sublingual route in correcting vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with T2D on metformin therapy. According to a recent literature review that included seven clinical trials assessing the efficacy of vitamin B12 supplementation in patients with T2D receiving metformin treatment, daily supplementation with methylcobalamin through oral or sublingual administration is preferred over the intramuscular route, considering its effectiveness, cost, and convenience for patients [57].

Given the lack of specific guidelines for the optimal treatment of vitamin B12 deficiency in individuals receiving metformin therapy, the MHRA [71] recommends following the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for managing vitamin B12 deficiency in the general population. In its most recent update, the NICE offers practitioners the option to choose between oral and intramuscular routes when malabsorption is not the cause of vitamin B12 deficiency [75]. It also mentions the possibility of offering intramuscular or oral vitamin B12 replacement to individuals with suspected or confirmed medicine-induced vitamin B12 deficiency [75]. Given the inconvenience of regular intramuscular injections and the evidence from several trials demonstrating the effectiveness of the oral route in normalizing vitamin B12 levels [57,73], we initially suggest a trial of oral replacement. Vitamin B12 levels should be checked 3 months later. If the vitamin B12 levels normalize, oral replacement may continue. Otherwise, the intramuscular route of administration should be considered. Vitamin B12 replacement should be continued as long as the patient is on metformin therapy.

Furthermore, calcium supplementation increased vitamin B12 levels in patients with T2D treated with metformin [35]. Numerous studies have demonstrated the beneficial effects of calcium supplementation on carbohydrate homeostasis [76]. Thus, calcium supplementation in patients with T2D can help prevent vitamin B12 deficiency associated with metformin intake and improve glycemic control. However, recent randomized trials and meta-analyses have shown that calcium supplementation is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events [77,78], making its use controversial in patients with T2D.

Regarding prevention, the British Society of Hematology states that it cannot provide recommendations on the indications for the prophylactic administration of vitamin B12 in patients with T2D treated with metformin [14]. However, such an approach is likely beneficial for patients receiving high doses of metformin over an extended period. Further studies are required to elucidate the benefits and risks of this preventive measure.

CONCLUSION

The relationship between vitamin B12 deficiency and chronic metformin use is well established, but the underlying mechanisms remain poorly understood. The risk of vitamin B12 deficiency is higher in patients with T2D receiving high metformin doses for an extended period or in the presence of other known risk factors associated with vitamin B12 deficiency, such as advanced age and regular use of acid-suppressing medications. Vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with T2D receiving metformin therapy increases the risk of developing or exacerbating peripheral neuropathy. The risk of anemia is also higher in these patients but appears to be independent of vitamin B12 status. However, its relationship with other cognitive and cardiovascular complications remains controversial. All these data highlight the importance of assessing vitamin B12 status in patients with T2D on metformin therapy, especially in those with risk factors and those presenting with neuropathy or other suggestive symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency. Vitamin B12 biomarkers should be measured when vitamin B12 levels are borderline. Identifying vitamin B12 deficiency requires an etiological investigation similar to the general population before diagnosing metformin-induced vitamin B12 deficiency. When diagnosed, metformin-induced vitamin B12 deficiency requires supplementation through oral, sublingual, or intramuscular routes. The vitamin B12 replacement protocol is similar to vitamin B12 deficiencies related to etiologies other than metformin. Metformin treatment should not be discontinued.